THE JOURNAL

The headgear of choice for a bit of the old ultra-violence. A Clockwork Orange, 1971. Photograph by Camera Press

Who are you calling old hat? We take a look back (and forward) at this formidable icon of British style.

What do Sir Winston Churchill, Mr Butch Cassidy, Bolivian cholitas and the clientele of the Korova Milk Bar all have in common? If you haven’t already guessed from the title of this piece, it is, of course, their choice of headgear. But how did the bowler hat, which became synonymous with businessmen in the City of London during the mid-20th century before falling out of fashion, become quite so popular? And could it be on the verge of a comeback?

Before answering these questions, we’re going to take a quick refresher course in the history of the bowler hat, which requires us to go back to Victorian England and the year 1849. The hat was named after its creators, milliner brothers Messrs Thomas and William Bowler, who designed it while working for Lock & Co Hatters, London’s oldest and most famous hat shop. The client in question was Mr Edward Coke, a politician, member of the landed gentry and brother to the second Earl of Leicester. Mr Coke was, by all accounts, a man of high sartorial standards – he even requested that his gamekeepers wore top hats while tending to his grounds. This caused all sorts of trouble, with low-hanging branches regularly knocking off and damaging their expensive hats while they were riding.

Gamekeepers wearing the bowler in the early 1900s, Holkham, Norfolk. Photograph courtesy of Lock & Co Hatters

Faced with a spiralling hat bill – #firstworldproblems – Mr Coke approached Lock & Co Hatters for a solution. They commissioned the Bowlers brothers to design a hat that was close-fitting enough to remain in place while riding and sturdy enough to provide some protection to the head. (In this sense, the bowler hat can be considered a precursor to the modern equestrian helmet.) When he was presented with the finished hat, Mr Coke is alleged to have dropped it on the floor and stamped on it twice to test its strength. Satisfied that it was up to the job, he paid the sum total of 12 shillings for it. The venerable Mr Coke was clearly a valuable customer; don’t expect such rigorous testing procedures to be tolerated while shopping around for your own headgear.

The bowler was a hit, quickly finding popularity as a cheap, everyman alternative to the top hat. It spread throughout the British class system and beyond, first to mainland Europe and eventually across the Atlantic. Contrary to popular opinion, it was the bowler, and not the cowboy or 10-gallon, that was the prevalent style of hat in the American Wild West. In South America, it has been worn by indigenous Bolivian women as a sort of national dress ever since British railway workers introduced it to the area in the early 20th century. But it’s closer to home, as part of the stereotypical image of an English businessman – along with a pinstripe suit, briefcase and neatly furled umbrella – that this iconic hat is best remembered today.

Quechua women wearing bombíns, La Paz, Bolivia, 2010. Bowler hats were introduced to Bolivia in the 1920s by British railway workers. Photograph by Tristan Savatier/Getty Images

According to Lock & Co Hatters, sales of the bowler hat peaked at some point in the late 1880s, when a few thousand were leaving the shop every year. (Exact figures are hard to come by, as the order books are currently stashed away deep in the London Metropolitan Archives.) “It’s an incredibly practical hat,” says Ms Hannah Rigby of Lock & Co Hatters. “It has a lower crown than the topper [top hat] and it doesn’t fall off the head so easily. It’s very protective, thanks to the shellac in its composition, and if fitted correctly – we use a conformateur – it should be comfortable to wear.”

So why, then, did we stop wearing it? The short answer is that we didn’t. The Square Mile’s once majestic parade of bowler-hatted bankers may have dwindled to all but nothing, but Lock & Co Hatters still sells the hats to an wide array of customers, from international tourists and history enthusiasts to county show judges and men in uniform. There are also a number of regular Nigerian customers, for whom the hat has become something of a status symbol. “It mustn’t be forgotten that the bowler is a unisex hat. We sell a fair amount to women, too,” adds Ms Rigby.

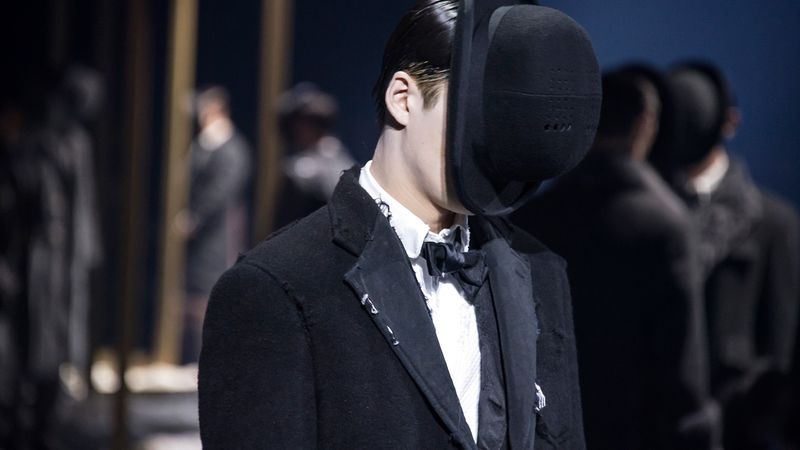

Hot tip: Mr Thom Browne’s AW16 show, Paris, 24 January 2016. Photograph by Kristy Sparow/Getty Images

And there are signs in the fashion industry that the bowler hat may yet be making a return. At last month’s Paris Fashion Week, the influential New York designer Mr Thom Browne presented a show set in the staged environment of a gentlemen’s club 30 years ago. Each look was displayed as a triptych, with a pristine original placed opposite two further versions in progressive states of decay, and all of the models’ faces were eerily obscured by tipped-forward bowler hats. Was this just for dramatic effect? Anybody who has seen one of Mr Browne’s shows before will attest to his taste for the theatrical. But according to MR PORTER’s Brand & Content Director, Mr Jeremy Langmead, who was in attendance that day, there was far more to it than that.

“Designers have always been clever at plundering iconic items from the past and giving them a modern look and a new relevance,” says Mr Langmead. “The bowler hat is so quintessentially British that it was only a matter of time before we rediscovered its charm and saw it creep back onto heads. There’s also an element of comfort in embracing items that we remember our fathers or grandfathers wearing, and nostalgia from having seen things worn in films or shows from the past: Mary Poppins, Mr Benn, The Thomas Crown Affair, The Avengers, A Clockwork Orange, Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid…

“As for Mr Browne,” he adds, “while you may think his ideas extreme, you’d be amazed how quickly they end up influencing – in a more subtle way – what we all might be wearing a year later.”

Smart droog: Mr Malcolm McDowell as Alex in A Clockwork Orange. Photograph by Allstar Picture Library

So, will the bowler hat ever make a comeback? Only time, as the hoary old adage goes, will tell. Perversely, the greatest barrier to its reintegration into the male wardrobe might be that it is just too iconic; it’s hard to look at one and not be reminded of all the men who have worn it, the films in which it has appeared and the professions with which it has become irrevocably associated over the years. If it isn’t the bankers and businessmen of London’s Square Mile, it’s Whitehall’s “bowler hat brigade” of civil servants. If it isn’t Mr Toshiyuki “Harold” Sakata as the evil, razor-hatted henchman Oddjob in Goldfinger, it’s Ms Liza Minnelli in Cabaret.

If there’s one thing we do know, though, it’s that the needle of fashion always swings back around. A man who wore a bowler hat in the 1950s and 1960s would have done so out of conventionality; in the 1970s and 1980s, it would have been out of fuddy-duddy conservatism; and in the 1990s and 2000s, sheer eccentricity. In what spirit would a man wear one today? To find out, we need look no further than where the hat was first made: the estimable Lock & Co Hatters of St James, London. “We’ve definitely seen a spike in sales of late,” confirms Ms Rigby. “Along with our regular customers, we’re also seeing quite a lot of guys who are buying them because… well, they look nice.”

Street style at Pitti Uomo, Florence, 13 January 2016. Photograph by Julien Boudet/BFA.com

That seems like a good enough reason to us. And by the way, if you’re still in any doubt about MR PORTER’s stance on the matter, then just look at our fifth anniversary logo. For what it’s worth, we’re giving the bowler hat our full support.