THE JOURNAL

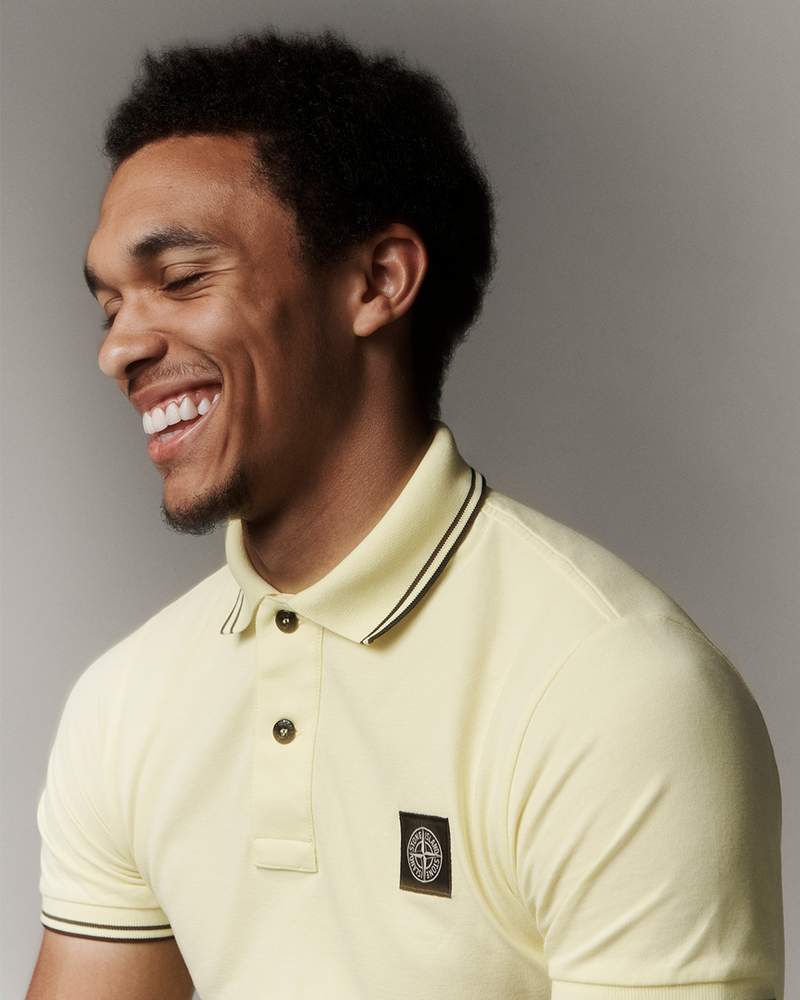

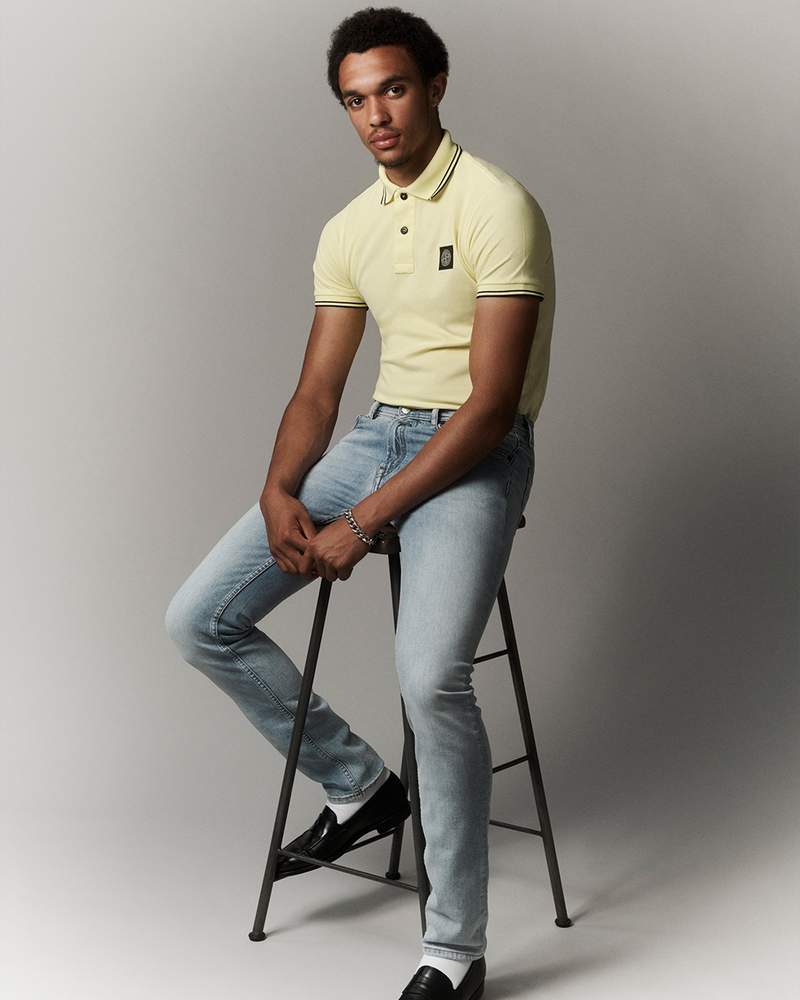

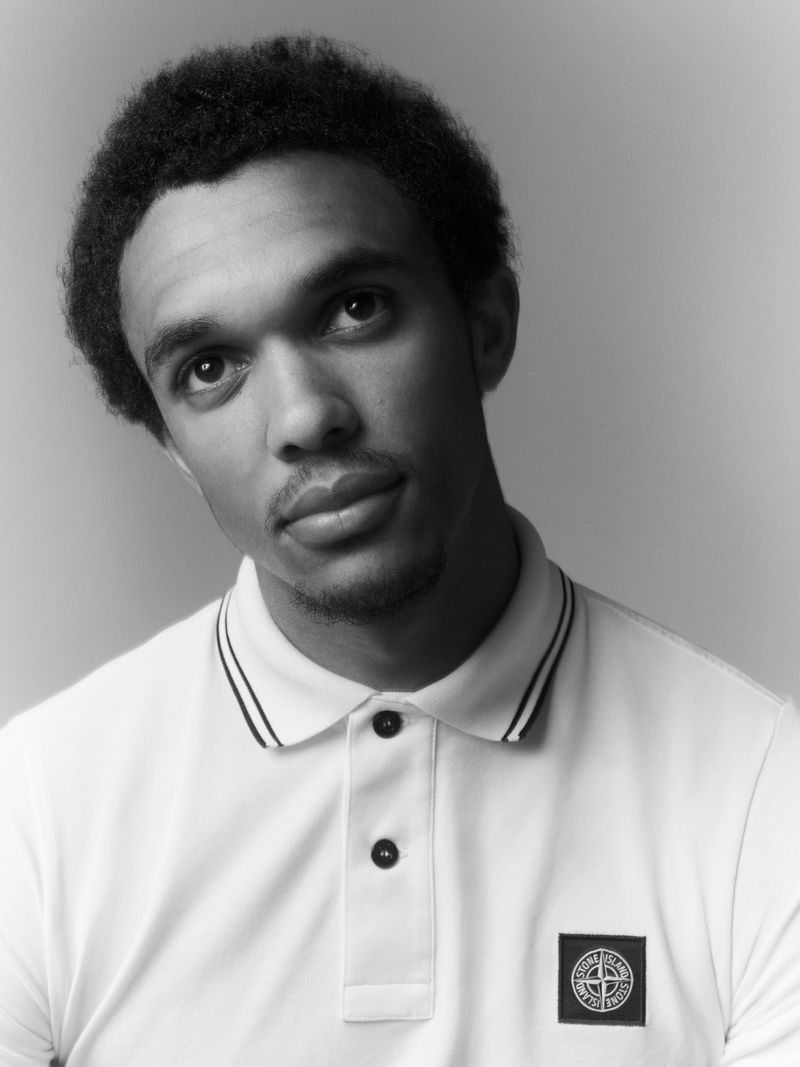

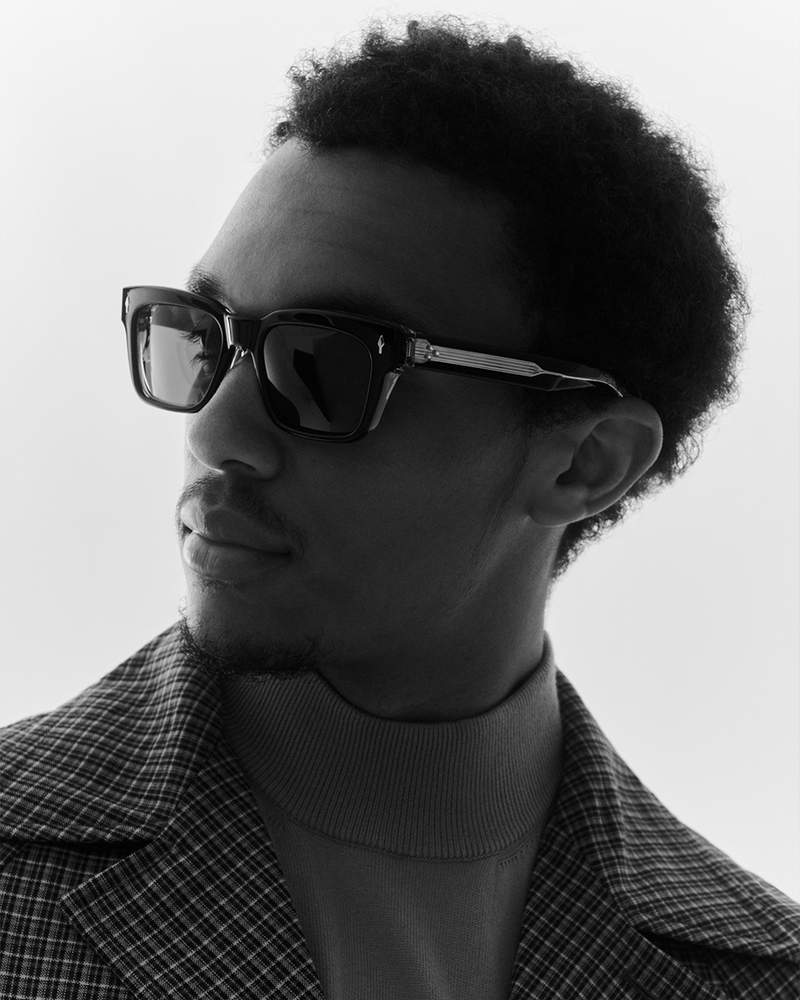

Liverpool FC’s Mr Trent Alexander-Arnold On Family, Success And Being A Hometown Hero

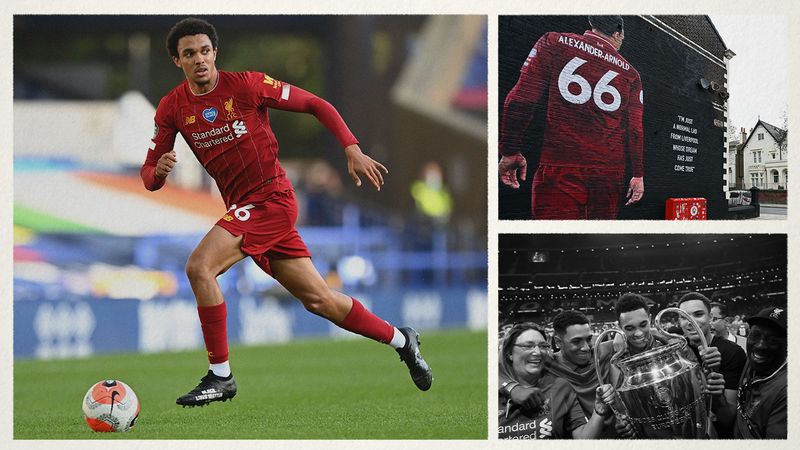

In the shadow of Anfield, Liverpool’s famous stadium, a woman traces her fingers across what was once a blank wall on Sybil Road. The faded brown brick has been transformed into a 26ft homage to a reference point for the community, and she is clearly stirred by the artwork, taking time to appreciate it from every angle.

It is a late July afternoon in 2019 and everything is quiet, which only serves to amplify her pride as she snaps a series of selfies. But this is not just any mural; this is not just any woman and this is not just any story. The painting salutes Mr Trent Alexander-Arnold, a Liverpool player since the age of six, for winning the Champions League a month earlier and for his contributions to Fans Supporting Foodbanks. The woman is his mother, Ms Dianne Alexander; a pivotal force in his development into one of the finest young footballers in the world and, more importantly, a fine young man.

“I’m just a normal lad from Liverpool, whose dream has just come true,” reads the inscription on the mural. The words have always been framed in a professional context: a Scouser securing club football’s supreme prize as a key member of his boyhood team. During a wide-ranging interview with MR PORTER, however, the 21-year-old England international reveals its true meaning for the first time. The mural is not only a portrait of the greatest night of life and a nod to his social work, it also offers a panoramic depiction of who he is.

Mr Alexander-Arnold grew up in a modest duplex on the fringes of Liverpool’s Melwood training base, which is located in the suburb of West Derby. His mother acted as what he describes as his “first coach”, drilling into him the values of consistency, persistence and discipline. His father, Mr Michael Arnold, advocated the importance of education, preparation and strategy.

A middle child, Mr Alexander-Arnold was flanked by two brothers. “Apart from the love, affection, support and encouragement I was surrounded with, competition is the other word that springs to mind about my household when I was a kid,” he explains. Mr Tyler Alexander-Arnold, four years his senior, now serves as the cultured right-back’s business manager. Mr Marcel Alexander-Arnold, who is three years younger, was Mr Alexander-Arnold’s roommate until they moved into a new home in 2016.

“My brothers and I had to share a lot of things like one football or one console and it drove that rivalry out of us,” he says. “Every day, there would be some series of competitions. When it came to sport or anything to do with athleticism, normally I’d win. Each of us had our strengths though, which made it interesting. Marcel was the best when it came to video games, while it was hard to get the better of Tyler in anything that required strategy, like chess or Monopoly.

“We are different, but we are very close,” he says. “I appreciate them a lot. I know how hard it must have been for them to sacrifice their dreams for mine, without having any clue over the end result. There was no guarantee over whether I’d only have one more season at the academy or whether I’d be one of the few fortunate enough to make it all the way through to the first team. They showed faith and trust in me, sidelining their desires to take a different path. I go out on the pitch with the intention of making it all worth it for them, too.”

“Every victory I have ever had is theirs. [My family] are my driving force”

It would be inappropriate to begin anywhere other than at the point that’s most important to Mr Alexander-Arnold – family. You can only truly understand the player and the person when you understand how much they ignite his ambitions.

“Every victory I have ever had is theirs,” he says, shortly before the resumption of a Premier League season that Liverpool has dominated. “They are my driving force. I remember when we got beat in the 2018 Champions League final against Real Madrid in Kiev. I wasn’t sad for myself or for the team, it was more for my family. I knew the sacrifices they had made for me, how proud they were, how excited they were for the game, how much the occasion meant to them. I was in control on the pitch, they were there just watching as fans and I was thinking of how hard it was for them and how upsetting it must have been for them to feel like they couldn’t influence anything. Looking towards the stand and seeing them so emotional was tough to take. It was the worst feeling.”

Mr Alexander-Arnold used their pain as his fuel for the 2018-2019 season. “That was my motivation,” he says. “That picture of how gutted they were… I didn’t want my family to feel like that again. I wanted them to be on the pitch with us celebrating, because my goal has been to win for them, rather than myself. When I saw the Real Madrid players and their families on the pitch, all I could think of was doing the same with my parents and brothers. I imagined it was us on the pitch, taking pictures together, cutting pieces of the net and being showered in confetti. I repeatedly played that thought in my mind over the course of the season, because I was desperate to make it happen.

“When we won the Champions League against Tottenham in Madrid and I said I was just a normal lad from Liverpool whose dream had come true, that’s what I meant. I was able to share that success with my family. The picture in my head became reality.”

The mural on the doorstep of Anfield, painted by street artist Akse, has subsequently taken on new layers of meaning. Commissioned by fan media group The Anfield Wrap as a way to salute a local icon, one who uplifts the community on and off the pitch, the original idea was to portray Mr Alexander-Arnold either holding the Champions League trophy or with the winner’s medal in-between his teeth while celebrating. It was the player who plumped for the image in which he is shown from behind. The work might celebrate his silver-lined story, but Mr Alexander-Arnold is the first to acknowledge it’s not all about him.

“That night – feeling like I made their dreams come true let alone mine – will live with me forever”

At the Wanda Metropolitano Stadium, where he crowned becoming the youngest player to start in consecutive Champions League finals by winning the first trophy of his career, his immediate thought following the final whistle was when he’d get to savour the achievement with those closest to him. “There was confusion as to whether the families were allowed to be on the pitch or whether they had to wait,” Mr Alexander-Arnold recalls. “I was itching to celebrate with them.

“I was mid-interview with [Liverpool legend] Jamie Carragher near the side of the pitch and my brothers ran up and jumped on me, the whole family joined in. We hugged for a long time and to see them so happy, I still actually can’t find the words to explain what that meant to me. I went to get the trophy as quickly as possible and bring it back for them, because it was their win, too. That night – feeling like I made their dreams come true let alone mine – will live with me forever.”

Mr Alexander-Arnold went through a taxing period of conditioning at Liverpool’s Academy before being deemed ready to deal with manager Mr Jürgen Klopp’s exacting demands. He believes both processes were aided by a “relentlessness at home”, where the expectation has always been that you give the best of yourself in whatever you do.

There has been an undertaking of growth within the family, too. “What we’ve all realised through this journey together is to understand each other better. If we’ve lost a game, for example, there’s an appreciation that I’m going to need some space and time to think about it. And when things are going really well, they keep me grounded, focused and determined. We’ve learnt a lot about each other, about ourselves, about setbacks and victories.

“When you’re a footballer, there’s so much talk about your development as a player. The big thing for me is that I’ve developed so much as a person through amazing guidance from my family, the academy and the first team set up. I never forget any advice I’m given.”

That last line is no cliché, as we’ll find out.

“When black lives do matter as much as everyone else’s, then all lives will matter. But that’s not the case now and it hasn’t been the case for centuries”

As with every Premier League player, Mr Alexander-Arnold’s surname was replaced on the back of his shirt with Black Lives Matter when football resumed after the near 100-day suspension on account of coronavirus. During Sunday’s Merseyside derby at Everton, the defender had those words emblazoned on his Under Armour boots, too. For generations, players were muzzled. There was a culture of colouring inside the lines for fear of being painted as problematic when it came to recruitment by other teams and sponsors.

“Just stick to football,” has been the instruction written into the Laws of the Game, which prevent players from exhibiting political, religious or personal slogans, statements or images.

The senseless killing of Mr George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police served to switch the play. Just as it jolted wider society across the globe, so it also unshackled players and forced a change in mood across the game. Fear was replaced by a desire to speak up and campaign for change.

Before the resumption of the Premier League season, footballers concurrently released a joint message under the #PlayersTogether initiative. “We stand together,” it stated, “with the singular objective of eradicating racial prejudice wherever it exists, to bring about a global society of inclusion, respect and equal opportunities for all, regardless of their colour or creed.”

Mr Alexander-Arnold will auction those BLM boots with all proceeds going to the Nelson Mandela Foundation. “Now we need to speak up,” he posted. “It can no longer just be our feet where we express ourselves. We have to use our profile, the platforms we have and the spotlight that shines on us to say, it’s time for meaningful change. The system is broken, it’s stacked against sections of our society and we all have a responsibility to fix it.”

He believes unity and education are imperative if we are to shred inequality. “When black lives do matter as much as everyone else’s, then all lives will matter,” he says. “But that’s not the case now and it hasn’t been the case for centuries. We have to push for change. It’s been too wrong for too long.

“When you’re able to reach so many people, especially young kids, you have to make sure that you can help them feel like anything is possible and help them grow up to have equal opportunities. They shouldn’t feel different to others and be denied the same chances in life just because of the colour of their skin, where they’re from or what their background is.

“For me, education is so important to all of this, because that’s where a lot of issues stem from. No one is born racist and comes into this world thinking that you deserve certain privileges based on skin colour or that you don’t deserve certain privileges based on skin colour. You get taught that. All of us have to work to undo that. So many people love football and I really hope they are absorbing the messages we are putting out there individually and through #PlayersTogether. I hope kids can see how much stronger we are when we are united, when we care about each other and when we’re committed to the greater good.”

Long before Mr Alexander-Arnold became a regular for Liverpool under Mr Klopp, he became an ambassador for An Hour For Others, a charitable organisation that encourages local people and businesses to give back to the community. He is plugged into the needs of his home city, which has suffered from government-imposed austerity. Since 2010, sustained cuts in successive budgets have left the Liverpool city council with £436m less to spend. Liverpool has to contend with the fact that 28 per cent of its children live below the breadline, a figure only set to climb due to Covid-19.

Mr Alexander-Arnold has been one of the champions of Fans Supporting Foodbanks, founded in 2015. The positioning of his mural was instructive, with it being on the street that the team bus drives past on match days and where the organisation would usually collect donations before every game. It is there as a public service announcement, to remind people to supply food to the less fortunate, if they are able to.

“I know I’m in a very privileged position and there’s never been any hesitation from me to use my platform for good or to help in any way that I can,” he says. “I had my role models growing up and I didn’t know them personally, yet their actions had a big impact on me. They did the right things off the pitch. They uplifted the community and they stood up for those less fortunate than themselves. That, and the way I was brought up, has influenced me and my natural thought process is ‘how can I help?’

“There’s no fuss about it. I want to make it easier for young players to come through, so I’ve been thinking of improving Sunday league pitches and facilities around Liverpool. Helping out the foodbanks or volunteering my time is just part of who I am. I know even the smallest acts of kindness can make a huge difference and why wouldn’t you want to help make life better for people if you can?”

“I want every trophy and as many of them as possible”

Mr Alexander-Arnold is in the embryonic stages of his career and yet he already counts the Champions League among his honours and has amassed over a century of appearances for one of the world’s biggest clubs. He hopes and expects to add a Premier League winner’s medal very soon, ending a 30-year wait for one of the most successful clubs in the game. Added to that, he is responsible for the “the smartest thing football-wise” that Mr Klopp – a leading light in management with 19 years of experience – has ever seen on a football pitch: his quickly-taken corner against Barcelona in the semi-finals of the European Cup last season set up the goal that took Liverpool to Madrid.

Clockwise from left: Mr Alexander-Arnold playing for Liverpool against Everton at Goodison Park in Liverpool, 21 June 2020. Photograph by Mr Shaun Botterill/AFP via Getty Images. Mural near Anfield, Liverpool, 18 April 2020. Photograph by Mr Paul Ellis/AFP via Getty Images. Mr Alexander-Arnold with his family following the UEFA Champions League Final between Tottenham Hotspur and Liverpool at Estadio Wanda Metropolitano, Madrid, 1 June 2019. Photograph by Mr Marc Atkins/Getty Images

Given how much he has already achieved, how will Mr Alexander-Arnold sustain his burning desire for silverware? “I want every trophy and as many of them as possible,” he says without a hint of reticence. “I remember [Liverpool’s academy manager] Alex Inglethorpe breaking it down into a thought process that I’ve never stopped thinking about since. It was when I was around 18 and he asked me ‘When do you retire? Maybe when you’re around 34 or 35.’ That’s 17 years. So, you’ve only got 17 attempts to win the Premier League, 17 attempts to win the Champions League or any other trophy. As much you think that’s a long time, the reality is you get only 17 tries and there will be failure, which is natural and will reduce that number.

“I’ve been in the senior team fully for three seasons,” he reflects. “The first try ended in a Champions League final defeat. The second, we missed the title by one point, but became champions of Europe. This season, we’re about to win the Premier League. So, I’m already thinking I’ve only got 14 more chances. Even though you can play hundreds of games, the fact is you only get a few attempts at silverware. I really pour everything into each season and focus on the here and now. It doesn’t help to think about the future and winning five or six trophies or whatever because you’re then losing sight of the opportunity in front of you to do something special. I know that if you get into that relentless habit, with a great team, a great manager and a great support structure, the chances will automatically be maximised.”

It’s no wonder that Mr Klopp describes Mr Alexander-Arnold as “the embodiment of the sentiment ‘We’re never gonna stop’,” which is part of an iconic Liverpool chant. And as such, he is the perfect representative of his club, his community, his city and – back to where it all starts – his family.