THE JOURNAL

The online revolution has transformed the way we shop, delivering the world’s finest items, without ever having to leave the house. But as convenient a service as this is, there remain a few lingering issues. For instance, when buying clothes, you can’t physically try them on first. Online stores (such as MR PORTER) will mitigate this by offering generous policies on returns and exchanges – and even using augmented reality tools to offer “virtual dressing room” features. However, there are still occasions when a customer might feel justified in opting for the inconvenience of visiting a physical store over the perceived risk of shopping online. One such occasion is when the garment in question is a suit.

A suit is not just a big-ticket item; it’s a complicated one, too, with a wide variety of measurements, fabrics and styles to consider before taking the plunge. Don’t let this put you off, though. As long as you do your research and order judiciously, there’s really nothing to fear – and it comes with the added benefit of never having to set foot in the tailoring section of a department store again. With that in mind, we’ve put together this very comprehensive guide to buying a suit online.

01.

The five suits every man should own

These things are a matter of personal opinion, of course, but here are the five suits we’d recommend for a well-rounded wardrobe. You’ll need nothing else.

01. A single-breasted two-piece suit in black, navy or charcoal grey

This is your workhorse, as apt for weddings as the working week. If you only own one suit, make it this.

02. An unstructured cotton suit in olive green or blue

An unlined suit in a lightweight fabric makes a great casual choice in warmer weather.

03. An unstructured linen suit in beige

It may be a less versatile fabric than wool or cotton, but the look and feel of a slightly rumpled linen suit is synonymous with summer. Take the Neapolitan approach and keep it unstructured (that means no canvassing or lining and minimal padding around the shoulder).

04. A double-breasted suit in a classic pattern, such as Prince Of Wales check

For special occasions, or for when you just want to make a statement, this is as classic as they come.

05. A tuxedo

You might only wear it a few times a year, but those are the moments when it pays to look your best.

Get the look

02.

Choosing a suit that fits

Mr Eddie Redmayne in New York City, 21 April 2021. Photograph by Goff Photos

How do I choose the right chest measurement?

Confusingly, there are two different conventions for labelling the size of ready-to-wear suits: the UK/US standard and the European standard. The former quotes the chest circumference in inches, while the latter quotes half of the chest circumference in centimetres.

So, if you have a chest measurement of 38 inches, you should fit a size 38 jacket in UK or US sizing. To find your equivalent European sizing, you have to convert 38 inches to centimetres and then divide it by two:

38 x 2.54 = 96.5 96.5 / 2 = 48.2

But if this sounds like too much unnecessary work, don’t worry – there’s a much simpler way of getting there. In order to convert your UK or US sizing into EU sizing, just add 10.

How do I choose the right trouser waist measurement?

Under standard circumstances, a pair of trousers sold as part of a ready-to-wear suit will have a waist measurement six inches smaller than the chest measurement of the suit jacket. That means, for example, that the corresponding trousers for a UK/US 38 suit jacket will have a 32-inch waist measurement. The difference between these two measurements is called the “drop”, and a normal six-inch drop is referred to as a “drop six”.

What if my waist isn’t exactly six inches smaller than my chest?

If you can’t find a ready-to-wear suit that fits your dimensions, one option is to buy separates – that is, a jacket and a matching pair of trousers that you can purchase separately. In fact, this is increasingly how suits are sold. At MR PORTER, look out for the words “PART OF A SUIT” on the product page along with a link to where you can purchase the other half of the suit.

What do the terms slim fit, regular fit and classic fit mean?

These terms largely do what they say on the tin. Slim-fit suits have a bigger taper from chest to waist, which serves to accentuate an athletic physique. You might find that a slim-fit suit has a “drop seven” measurement, which means that the waist measurement is seven inches smaller than the chest measurement. It will often have a greater taper in the leg, too. Regular-fit suits are more generously tailored, and classic-fit suits even more so. With that in mind, though, it’s worth remembering that the suit is constantly evolving, and as such it is hard to offer a precise definition of “regular”, “classic” and “slim”.

What other measurements should I be aware of?

The rise – that’s the measurement between the waistband and the crotch – tells you how high-waisted your trousers are. Keep an eye out for the trouser-hem measurement, too, which gives an indication of how slim the trousers are. The degree of taper from thigh to hem can have a big effect on the overall look of a suit. A more aggressive taper gives a sharper, slimmer silhouette, while a wider trouser hem looks more relaxed. (For reference, a regular fit is around seven inches or 18 centimetres, although, as we’ve just mentioned, the current definition of “regular” is subject to the whims of fashion.)

When my suit arrives, how will I know that it fits?

In a physical store, you’ll have the advantage of a sales assistant to advise you on fit. When ordering a suit online, this is something you’ll have to do for yourself. The good news? This isn’t difficult. Here are a few things to look out for:

- The shoulder seam joining the sleeve to the body of the jacket should line up with the outer point of your shoulder. If the seam juts out beyond your shoulder, it’s too big. If your shoulder pushes into the sleeve of the jacket, it’s too small.

- The collar should sit flush against the back of your neck when you stand up straight with your jacket fastened. If you can slide your finger between the collar and the back of your neck, it’s too big.

- You should be able to cross your arms without feeling the fabric of the jacket stretch across your back. If it does, the jacket is too small.

- When buttoned, the jacket’s lapels should sit flat against your chest. If buttoning the jacket pulls them out of shape, that means that the jacket is too small.

- The hem of the sleeves should finish just below your wrist bones when standing up with your arms flat against your body. They should not lift up beyond your wrists when you raise your arms forward.

- You should be able to easily button your trousers when standing up. If the waistband is even slightly tight when standing up, it will press uncomfortably against your hips when sitting down.

Get the look

03.

The different types of suit, explained

Two-piece or three-piece?

The standard two-piece suit consists of matching jacket and trousers. This is your typical suit, and by far the most common style available. The three-piece suit includes a matching waistcoat designed to be worn under the jacket. A more formal option, the three-piece is a popular choice for special occasions such as weddings or a day out at the races.

One, two or three buttons?

A suit jacket with three buttons will have a high fastening and a short lapel. While this look has its fans – it was popular with the mod movement – it can have the effect of making the torso appear shorter, as the elongating V-shape created by the plunging lapel is smaller and less conspicuous. The “three-roll-two” construction popular with high-end Italian tailors counteracts this by allowing the lapel to roll down when the top button is left unfastened. This technique is used to great effect by Caruso.

A two-button fastening is the most popular configuration today, while one-button fastenings are most commonly seen on tuxedo jackets or jackets from specialist tailors, such as Savile Row’s Huntsman. A one-button suit can give the impression of a more cinched waist, as the hem of the jacket is able to flare out a little more. Having said that, you can easily achieve the same effect by leaving the lower button on a two-button fastening undone. The one-button vs two-button debate is, therefore, mostly a question of personal taste.

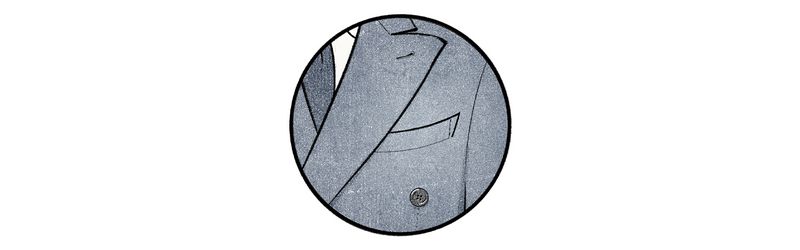

Single-breasted or double-breasted?

Broadly speaking, suit jackets come in either single-breasted or double-breasted configuration. Single-breasted jackets fasten with a single, vertical row of buttons, while a double-breasted jacket has two rows of buttons. In general, double-breasted jackets are a touch more traditional and can lend an air of stately respectability to the wearer – but they can also add bulk.

Of course, it goes without saying that not all double-breasted (DB) jackets are the same. They are distinguished from one another by their number of buttons – and how many of them are functional. As you’d expect of the arcane world of gentlemen’s tailoring, this convention has its own numerical system. You’d say “six on two” or “six by two” to describe a DB jacket with six buttons, two of which are functional. (This is written as 6x2.)

Button positioning varies, too. A common feature of six-button DB jackets with wide lapels, the top two buttons are often placed wider apart than the bottom four buttons to account for the spread of the lapel. To most, this gives a more traditional feel with a narrower alignment of buttons.

As very few of these buttons are functional, this is again a matter of personal taste.

British or Neapolitan?

There are countless regional variations on the suit, but the two that have made arguably the biggest impact hail from London and Naples. If you’re fond of sweeping generalisations, you could say that the British style is more structured, and the Neapolitan style less so. Though there is, of course, slightly more to it than that – a distinction we’ll breeze over in the most cursory fashion, as it’s a topic that entire books can be (and have been) written on.

The British take on the suit is characterised by a sharp, heavily padded shoulder, a suppressed waist and a longer jacket. These details create a strong, angular silhouette. TOM FORD, Thom Sweeney or anything with a Savile Row influence is a good example of the British tailoring style.

By comparison, the Neapolitan jacket, which was designed for a warmer climate, has an unpadded shoulder, minimal lining and more closely follows the natural lines of the body. Neapolitan tailoring is often described to give a “shirt-like” fit. Rubinacci’s one of the key proponents of this style of tailoring. (Indeed, the brand can even claim to have invented it – Mr Vincenzo Attolini was the first to pioneer this radical take on the suit while employed as a cutter at the brand in the 1930s.)

Get the look

04.

Suit alterations, explained

What’s with the unfinished trouser hems?

The trousers of any well-made suit will be delivered with their hems left unfinished. This is done for a very good reason, which is that men’s legs vary greatly in length, and a pair of trousers that are either too long or too short can ruin the appearance of a suit.

Any local tailor will be happy to finish the hems of your trousers. When you visit them, be sure to take the shoes you intend to wear with your suit, as it is the contact with those shoes that will determine the “break” of your trousers. This word refers to how much the fabric of your trousers creases when it brushes the top of your shoe.

At one extreme, a trouser leg with no break barely touches the top of your shoe at all, potentially leading to visible socks while standing up. At the other extreme, a trouser leg with a full break has a full fold of fabric at the ankle.

While trouser break is a matter of personal taste, we’d recommend opting for a slight break over no break at all. That little bit of extra material will come in handy when you sit down and your trousers naturally ride up. And whatever you do, try to avoid “puddling” – that’s when too much excess fabric puddles around your ankles.

Should I unpick the stitching in the pockets?

Yes. The stitching is put there to stop people who are trying the jacket on before buying it from stuffing their hands into the pockets and ruining the lining. Once the suit is yours, feel free to take the stitches out.

If my suit doesn’t quite fit, can I take it to the tailor and have it altered?

Yes – to an extent. Ready-to-wear suits aren’t made to be altered in the same way as bespoke suits, which are tailored with excess fabric behind the seams in the expectation that they will need to be enlarged at some point in their lifespan. You should still be able to take your ready-to-wear suit in, but without this excess fabric it’s much harder to let it out.

One of the easiest and most impactful adjustments you can make is to the length of the arms. If the sleeves on your new jacket are too long – and we’ve explained above how you can recognise this – a tailor or a good dry cleaner should be able to shorten them for you. Don’t hesitate to have this done. It’s relatively cheap, it doesn’t take long and it can make the difference between nearly perfect to spot-on.

There are also certain areas of a suit that can’t easily be altered, such as the shoulders and the collar. If those parts don’t fit, it might be simpler to send the suit back and try out a different size.

Get the look

05.

A guide to suit fabrics

Worsted

A smooth woollen yarn made from long-staple fibres, worsted makes a smooth cloth that is commonly used in formal suits. It is named after the town of Worstead in Norfolk, UK.

Tweed

An often colourful, rough woollen fabric originating from Scotland’s Outer Hebrides and the northern tip of Ireland. Synonymous with country pursuits.

Velvet

A rich, luxurious fabric often used in eveningwear, it is made from a looped cloth that is cut and then brushed for a soft texture.

Corduroy

A napped fabric constructed in a similar way to velvet, only with raised ridges or “wales”. Usually made from cotton.

Flannel

A soft, napped cloth usually made from wool, it is a popular choice for casual cold-weather suiting.

Linen

A lightweight textile made from the fibres of the flax plant. Because of its breathable qualities, linen is the perfect material for hot weather.

Cashmere

A very fine wool sourced from the undercoat of the cashmere goat.

Merino wool

A fine wool sourced from the Merino sheep, much prized for its naturally breathable properties.

Super 60s, 80s, 100s, etc

A categorisation used to describe the fineness of woollen fibres. Anything higher than

100s makes a very fine, lightweight fabric that can feel almost like silk.

Twill

A weaving method distinct from open weave, twill is easily distinguishable by its pattern of diagonal ribs. Drill, herringbone, houndstooth and denim are all examples of twill-woven fabric.

Gabardine

A tightly woven twill with a diagonally ridged surface, gabardine is traditionally made from either worsted wool or cotton. Cotton gabardine is very durable and has water-resistant properties, making it ideal for raincoats.

Hopsack

A type of basket weave popular in summer tailoring, it has breathable and crease-resistant qualities.

Seersucker

A slightly puckered cotton fabric traditionally worn in summer, especially in the southern US states. The name is derived from “shiroshakar”, which is Persian for “milk and sugar” and is said to refer to the smooth and rough textures of the fabric’s alternating stripes.

Herringbone

A V-shaped weaving pattern that resembles the bones of a herring fish. It is used in the manufacture of tweed and was also seen in US Army fatigues, where it was referred to as herringbone twill or HBT.

Houndstooth

A woven twill pattern with an abstract checked appearance, commonly seen in black and white or black and grey duotone.

Pinstripe

A pattern of very fine vertical stripes that is traditionally associated with conservative business attire.

Chalk stripe

A cloth with slightly thicker stripes that are designed to resemble the lines drawn by a tailor’s chalk.

Windowpane check

A widely spaced check pattern that resembles the divided panes of windows, hence the name. This pattern makes a bold sartorial statement when worn with colour.

Tartan

A coloured check pattern particularly associated with Scotland, where it can be used as a signifier of a person’s clan. Tartan trousers, or “trews”, are a popular choice on formal occasions.

Prince of Wales check

A pattern of small and large checks made popular by the Duke of Windsor, Edward VIII, when he held the title of Prince of Wales. It is also known as Glen check, after the Glenurquhart Valley in Scotland where it was first made.

Brocade

A decorative technique whereby patterns are woven into the fabric, often with gold or silver thread or coloured silks. This gives the effect seen on elaborate tuxedo jackets.

Get the look

06.

A guide to suit details

Pockets:

Barchetta pocket

A pocket with a slight upward curve that resembles the bow of a boat (barchetta means “little boat” in Italian). This is a common feature in high-end Neapolitan tailoring.

Patch pocket

The simplest type of pocket, a patch pocket consists merely of a piece of fabric that has been stitched onto the outside of the jacket.

Jetted pocket

A pocket tailored to sit inside the jacket, it appears from the outside as a slit bordered by two thin strips of fabric, or “welts”.

Flap pocket

A jetted pocket finished with a flap of fabric designed to keep the contents of your pocket secure.

Ticket pocket

An additional, smaller pocket just above the right hip pocket, the ticket pocket is a common feature on Savile Row-style suits and was originally designed to provide commuters with somewhere to store their train tickets and spare change.

Lapels:

Notch lapel

The most common lapel feature, characterised by a V-shaped notch where the fabric of the lapel meets the fabric of the collar.

Peak lapel

A lapel that forms an upward-pointing peak where it meets the collar. This is common on double-breasted jackets and formal attire such as black or white tie.

Shawl lapel

A sweeping lapel with no notch. This is commonly seen on tuxedos or velvet jackets.

Construction details:

Side tabs

Buckled straps on the side of a pair of trousers that can be used to adjust the fit. An alternative to belt loops.

Canvassing

A structural layer positioned in between the outer fabric and the lining of a jacket to ensure that it drapes properly and maintains its structure over time. Traditionally made of horsehair, it is a hallmark of Savile Row-style tailoring. Jackets can be fully canvassed or partially canvassed.

Lining

This is an additional layer stitched to the inside of a jacket, adding warmth and structure. Fully lined jackets have a lining that covers the whole of the inside of the garment. Partially lined jackets will only have a lining on the sleeves and the upper part of the torso. Very lightweight jackets tend to come unlined.

Spalla camicia

A puckered shoulder created by stitching pleats into the sleeve where it meets the body of the jacket. A hallmark of Neapolitan tailoring, it allows for a little more flex in the upper arm and lends the jacket its distinctive shirt-like appearance.

Con rollino

Another Neapolitan detail, this is a shoulder construction featuring a slight ridge of additional fabric where the sleeve meets the jacket. It gives the impression of a wider shoulder without the need for padding.

Get the look

Illustrations by Mr Jori Bolton