THE JOURNAL

The Colosseum, Rome, June 2016. Photograph by Mr Edwin Remsberg/Superstock

Rome wasn’t rebuilt in a day – but thanks to Italy’s biggest brands, the nation’s landmarks are being restored.

For as long as anyone can remember, the travertine blocks of the Colosseum, monolithic symbol of Italy, were the colour of a day-old bruise, blackened by the soot of 2,000 years, pockmarked by acid rain and pollution, and made wonky after centuries of cold nights and scorching Roman days, not to mention the odd earthquake. Well, just take a look at it now. The scaffolding that had swathed the icon since 2013 has been removed and, after the first phase of a three-year restoration, it gleams creamy white by day and even flushes pink as the sun sets. You can clearly make out the Doric and Ionic columns placed delicately between the arches. Beneath the grime, archaeologists have made discoveries such as carved rosettes and medieval frescoes.

Take a walk around the Italian capital this summer and you’ll soon find the Colosseum is far from the only monument not showing its age. The 18th-century Trevi Fountain, featuring horn-blowing mermen, heaving hippocampi and the water gods astride a seashell chariot, no longer looks like it might crumble at any moment. (A large chunk did fall off in 2012.) It’s as good as new after a 17-month restoration, which had forced tourists to toss coins in a different pool. Nearby, the Spanish Steps are so clean you could eat your pizzetta off them, thanks the 82 craftsmen who restored the 4,619sq ft of stone.

It’s not just Rome’s treasures that are enjoying a facelift. Milan’s Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, next to the Duomo, has been scrubbed up nicely. Florence’s Uffizi gallery has renovated eight rooms containing its 15th-century collection. In Venice, the scaffolding recently came down on the restored Rialto Bridge.

Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, Milan, August, 2016. Photograph by Mr David Burdeny

What to pack

What is even more remarkable than the renaissance of the monuments is how they’ve been transformed. It’s the work of a group that has been dubbed the “Monuments Men” – fashion designers and leading luxury goods entrepreneurs who have invested tens of millions of euros in a new kind of vintage collection: heritage.

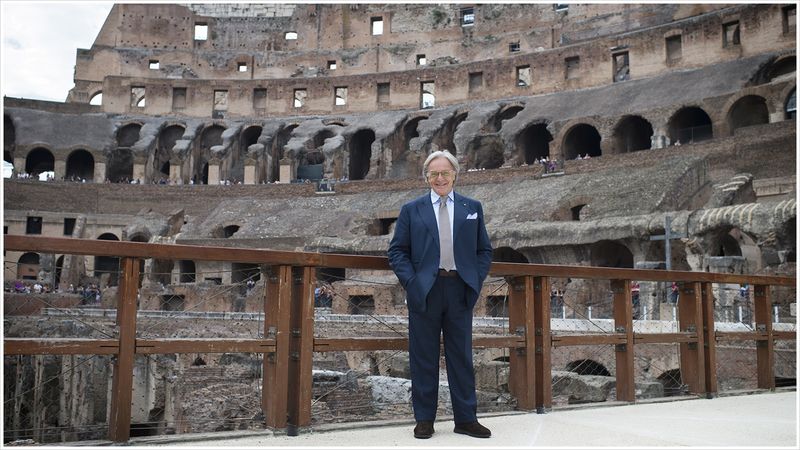

It started with Mr Diego Della Valle, president and CEO of Tod’s, who pledged €25m to restore the Colosseum, the costliest project. He responded to a call from the mayor of Rome for private-sector funds. “As soon as I heard they were looking for a sponsor, I couldn’t do anything other than put myself forward,” he said. “Businesses that are lucky enough to do well should give back a little bit to their country.”

Fendi answered the call to save the Trevi, spending €2.2m to clean the statues and fix the cracks in the marble. The €5m Rialto project has been sponsored by OTB Group, the parent company of Diesel, Maison Margiela and Marni. The Salvatore Ferragamo fashion house, based in Florence, donated €600,000 to restore the wing of the Uffizi Gallery. Prada and Versace – a most unlikely double act – went halves on the Milan Galleria. Bulgari funded the Spanish Steps work to the tune of €1.5m.

Spanish Steps, Rome, September 2016. Photograph courtesy of Bulgari

What to pack

For Fendi, the Trevi Fountain was a natural fit. The company, now owned by LVMH, was founded in 1925 in a small fur workshop and bag store less than a 10-minute walk from the monument. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Fendi family even produced a film and a book on the fountains of Rome. Ms Silvia Venturini Fendi, granddaughter of the founders, said the city’s mix of classical and baroque architecture was the inspiration for the company’s famed Baguette handbag. “Rome is the perfect place for a designer to get inspiration,” she says. “It’s like walking in an open-air museum.”

For Mr Ferruccio Ferragamo, chairman of the Salvatore Ferragamo Group, the motivation to donate money to Florence’s foremost art gallery/museum was history – personal as well as national. “My father migrated to the US when he was very young, and then came back to Italy and chose Florence as his city and his company’s headquarters. The air that my father – and we all – breathe here is inspirational.”

The painstaking work began in 2013, five years after the global financial crisis, when the Italian government admitted it was too cash-strapped to restore the country’s, if not the world’s, most important monuments. Funding for the maintenance of Italy’s archaeological riches was slashed by 20 per cent in 2010.

Fendi Roma 90 Years Anniversary Fashion Show at the Trevi Fountain, Rome, 7 July, 2016. Photograph courtesy of Fendi

What to pack

But the new investments are not just “billanthrophy”. Fashion labels have a direct stake in maintaining Italy’s glamorous image. It’s no coincidence that the monuments chosen for rescue are among the country’s best-known. It also helps that brands receive a tax credit over three years equal to 65 per cent of the expenditure.

Fashion’s reverse takeover of heritage initially outraged some of Italy’s cultural purists. They protested that logos would soon plaster the national monuments. (A few did appear on the Rialto.) Italy’s heritage would be on a slippery slope to privatisation. Indignation ran high in Florence after it was discovered that city officials had allowed Morgan Stanley to hold a dinner inside a 14th-century chapel for a rental price of $27,000. Florence’s mayor doubled the rent to $54,000 after the outcry, but some argued that price was not the core issue. “There are sacred places where one can simply not hold a dinner,” complained Mr Salvatore Settis, an expert in cultural heritage law and a former director of the J Paul Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. “Not even for €4 million.”

But such concerns have now dissipated. The only place the Tod’s name appeared during the Colosseum restoration was in tiny lettering on the legally required restoration signs. Fendi has received nothing for its donation, except a 30 x 40cm plaque, fixed to the side of the fountain for three years.

Hall 25 in the Uffiizi Gallery, Florence showing Mr Domenico Ghirlandaio’s “Adoration of Magi”. Photograph courtesy of Ferragamo

What to pack

However, the companies’ interventions have gained them the kind of publicity money can’t buy. And they have not been shy to celebrate the end of restoration work. Ms Kendall Jenner walked across a glass-topped Trevi Fountain in a blue astrakhan coat with full swing skirt, in front of guests that Fendi had flown in by private jet from the couture shows in Paris, to celebrate the reopening of the icon. “It will go down,” wrote Ms Nicole Phelps in Vogue, “as one of the most majestic show venues ever.” Bulgari also hosted a lavish soirée at the Spanish Steps to celebrate their restoration.

Will the new vogue for vintage endure? A country that’s home to more Unesco World Heritage Sites than any other could certainly use it. Fendi has committed to restoring four other fountains in the capital, including the 16th-century Fountain of Moses on the Quirinale Hill, and the next phases of the the Colosseum work is under way. Underground passages and catacombs are being shored up, the hypogea and ambulatory will be restored and a new visitors’ centre and cafeteria built.

Mr Diego Della Valle at the Colosseum, Rome, 1 June 2016. Photograph courtesy of Tod’s

Other fashion entrepreneurs are restoring important artefacts of Italian culture. In 2015, Mr Federico Marchetti, founder of YOOX and CEO of the YOOX NET‑A‑PORTER Group, unveiled a restored version of Mr Federico Fellini’s film Amarcord at the Venice Film Festival. After producing Ms Alison Chernick’s The Artist Is Absent documentary on fashion designer Mr Martin Margiela, Mr Marchetti teamed up with Italian film institution Cineteca di Bologna to restore Mr Fellini’s legendary film, which won the Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award in 1975 for its portrayal of the daily life of ordinary people in the seaside resort town of Rimini in the 1930s.

Mr Marchetti – who was made a knight (“cavaliere”) in June by the Italian president – explained: “For me, as a native of Romagna, Amarcord is a special work: a waking dream that makes me feel at home, a memory of my childhood. It’s no coincidence Amarcord in local dialect means ‘remember’. I hope it will inspire future generations, as it has for myself. It’s a warning not to lose sight of our roots while continuing to innovate and look to the future.”