THE JOURNAL

Photograph by Mr Daniel Bruno Grandl

From Louis Vuitton to Burberry, even the most venerable houses are taking to the streets.

Last year, the biggest story in menswear was the unlikely collaboration between Louis Vuitton, a French luxury “maison” with a history that spans three centuries, and Supreme, a New York streetwear brand with origins in the anti-corporate skate culture of the 1990s. This logo-heavy collection would have been impossible to imagine until very recently, but it spoke volumes about the style world’s current taste for streetwear.

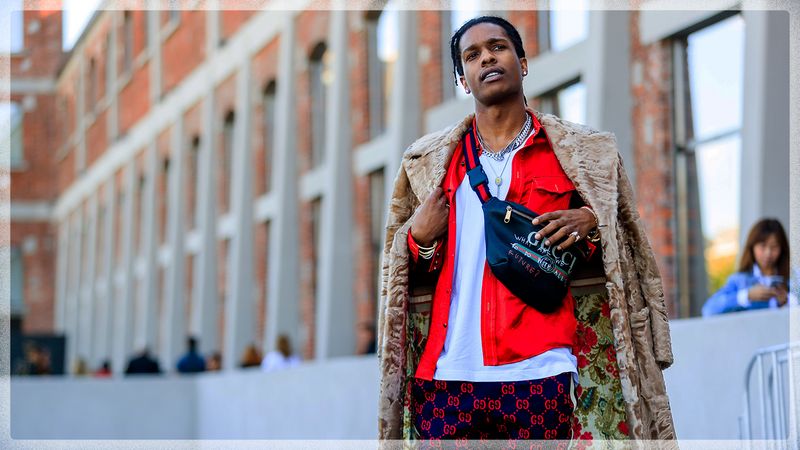

That taste explains why Burberry’s latest collection, launched in February 2018, features many casual pieces, including baseball caps, sweatpants and Harrington jackets bearing the brand’s famous check. These are exactly the sort of designs that Burberry has been trying to live down since its clothes became closely associated with Britain’s so-called “chav” culture in the early years of this century. Of course, “chav” culture is just a very rude term for street culture. Burberry is simultaneously producing other heavily branded items in collaboration with Mr Gosha Rubchinskiy, the Russian designer who is currently among the hottest names in fashion thanks to his interpretations of the kind of proudly unsophisticated streetwear that was popular when Russia first embraced capitalism in the 1990s. (That decade’s fashions are an inspiration to many of the current slew of streetwear and street-inspired designers.) Meanwhile GQ’s UK edition recently declared rapper A$AP Rocky (who, last season, was the face of Dior Homme) to be the second best dressed man in the world, Gucci is working with veteran New York bootlegger Dapper Dan, and Mr Kanye West is one of the world’s most talked about designers.

Photograph by Mr Pelle Crepin

What exactly is going on? Since the birth of luxury fashion as we know it, designers have always worked with a vision of exclusivity extrapolated from the lifestyles of elites. Ralph Lauren has made billions from casual clothes that serve up the dream of Ivy League style. Jackets and suits are marketed based on their close – or ideological – links to the old-money tailors of London’s Savile Row, or Naples’ Chiaia district. However, in 2018, casual clothes are inspired by sportswear and vintage knock-offs. Tailoring still exists, of course. But the boxy shapes of the suits from trend-creating brand Balenciaga call to mind formal work outfits worn by real men in dreary offices – in short, the clothes explicitly deny any phony links with old European tailoring traditions. Even cerebral, minimalist label Jil Sander has, in co-creative director Mr Luke Meier, got an ex-Supreme designer calling the shots. Have forthright millennials rejected the fashion business’ traditional sales pitch, which is to offer social advancement through dressing up like one’s “superiors”? Yes, it seems so.

The early signs that streetwear was going to influence fashion emerged nearly a decade ago. According to Mr Matthew Henson, fashion director of AWGE, A$AP Rocky’s creative collective, the AW08 fashion show for Mr Sean Combs’ label Sean John was important. “It shifted things,” Mr Henson says. “It encompassed so many elements of menswear that it shifted the perception of what streetwear brands were known for.” A year later, Mr Pharrell Williams designed a small collection for Moncler, which memorably included a down-filled “bulletproof” vest. Mr Sam Lobban, buying manager at MR PORTER, highlights the commercial logic at work: “There’s a correlation between the streetwear sensibility and where high-fashion brands see an opportunity in the marketplace. I can’t see it changing because the brands have broadened their customer base by making clothes that are easy to wear and what most guys really want.” Another perspective is offered by Mr David Fischer, the Germany-based founder of the Highsnobiety fashion website. He believes that the current trend is down to the fashion industry’s wish to remain relevant: “Streetwear speaks to a highly influential young audience that the high-fashion industry desperately needs to get in touch with.”

A$AP Rocky. Photograph by Frenchy Style/Blaublut Edition

When it comes to the origins of the current trend Mr Lobban is quite clear. “You can’t have this conversation without talking about Kanye [Mr Kanye West], because it was his 2011 Givenchy collaboration for the Watch The Throne tour – a combination of street fashion, hip-hop culture and a storied French house – that started this in the first place. There’s a direct line from him to the consumer appeal of high fashion. Watch The Throne was the first time that far more people were exposed to high fashion.” Mr Kanye West began to straddle the worlds of hip-hop and fashion with his “Louis Vuitton Don” persona in the middle of the last decade; in 2009, he interned at Fendi’s Roman offices and designed sneakers for Louis Vuitton. In 2014, he collaborated with A.P.C., and in 2015, he launched his Yeezy brand. Two years before Yeezy’s first offering sold out, Mr West foretold the rise of streetwear in a 2013 interview with BBC Radio 1. Frustrated by the fashion industry’s reluctance to engage with him (and hip-hop culture in general) Mr West expressed disdain for the rock ’n’ roll aesthetic that designer Mr Hedi Slimane had just introduced at Saint Laurent. He declared, “We the culture. Rap is the new rock ‘n’ roll. We the rock stars. It’s been like that for a minute, Hedi Slimane!”

It’s a message that Gucci, which is currently enjoying a symbiotic relationship with Atlanta rappers Migos, is expressing through its surprising new project with New York designer Dapper Dan. In the 1980s, Dapper Dan dressed rappers like Eric B & Rakim in leather tracksuits bearing all-over monograms from fashion brands that had never given their blessing to his creations. In a reciprocal incident last year, Gucci was criticised for copying a 1989 Dapper Dan design for its Cruise 2018 womenswear collection. The Italian brand has responded by setting up Dapper Dan with an “atelier” in a Harlem brownstone from which he is creating made-to-order Gucci collaborations for men (A$AP Ferg has requested a goose-down jacket with a pink patent-leather yoke). In January, Dapper Dan said of the project, “Nothing elevates our fashion culture better than having it our way.” Is streetwear’s dominance simply down to the fashion industry’s belated recognition that hip-hop now defines youth culture?

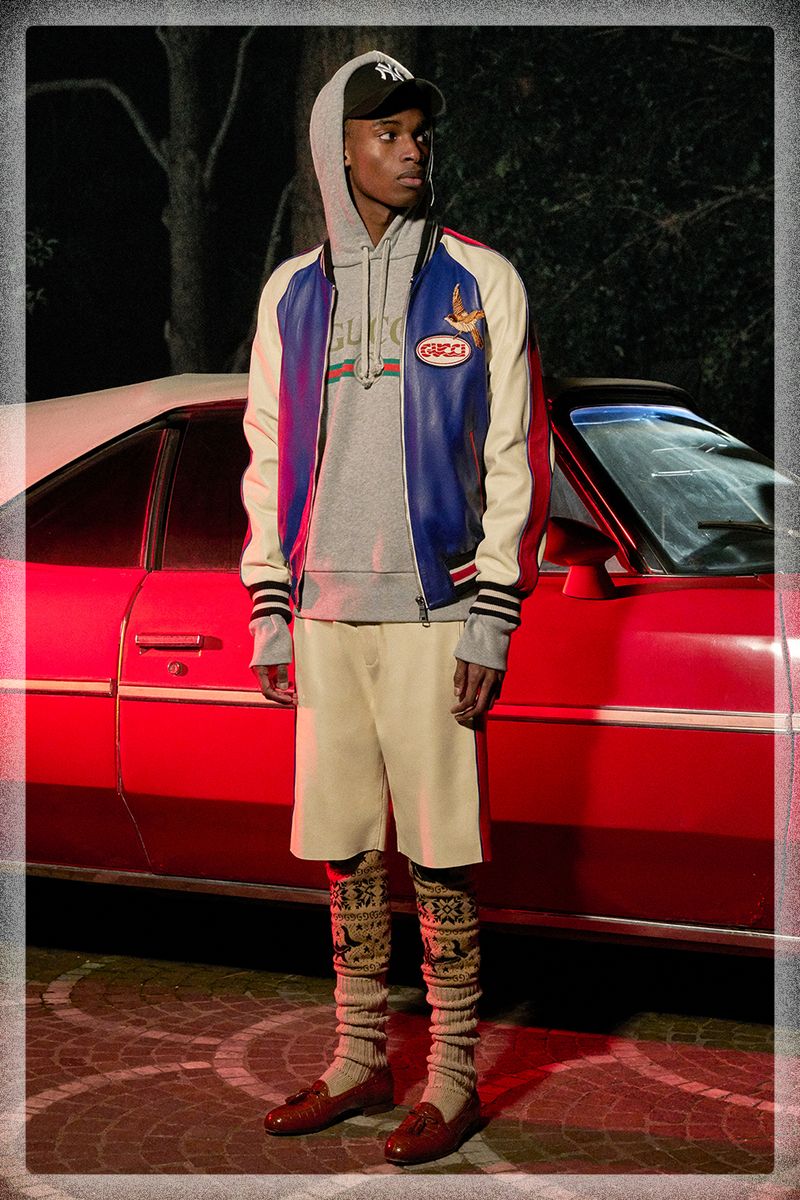

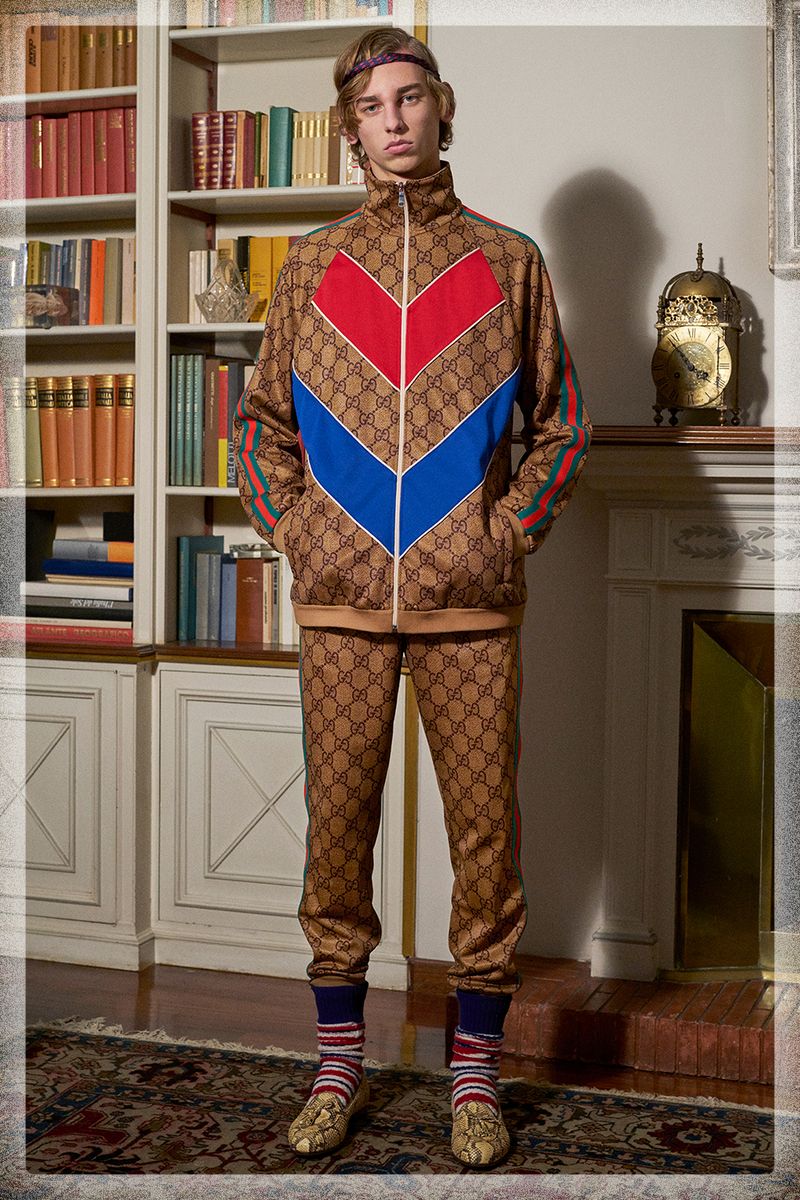

Photograph by Mr Peter Schlesinger courtesy of Gucci

Photograph by Mr Peter Schlesinger courtesy of Gucci

Perhaps, but Mr Nick Sullivan, fashion director of Esquire magazine, believes technology is the real driver. “I think the streetwear explosion is a natural corollary of the growth of Instagram,” he says. “It democratised fashion for many. Unfortunately, you can’t democratise taste, so there’s a lot of silliness that has come along with it and an explosion of logos visible from space. People aren’t into design right now, they’re into impact.” Mr Lobban also acknowledges the power of Instagram. “Guram [Mr Guram Gvasalia, co-founder of Vetements] told me that some design details are driven by Instagram. On the brim of the hoodies there’s a logo and the season, because Guram saw people were putting up the hoods when they took selfies.”

Thank hip-hop, or thank Instagram, because streetwear’s rise is definitely a good thing, whatever you think of Vetements’ oversized hoodies, Mr Rubchinskiy’s high-end football kit or the preponderance of logo-spattered T-shirts that are currently doing the rounds. The reality is that fashion’s most creative moments have come when designers are attuned to what is happening on the streets – examples include the explosion of self-expression in the late-1970s punk scene in London, the creativity and sexual liberation of the club scene of the 1980s and the socially inclusive rave culture of the 1990s. It is no coincidence that all three of these movements emerged at economically uncertain times when dressing up no longer appealed.

Photograph by The Urban Spotter/Blaublut Edition

Could it be that millennials, who in Western countries have little hope of becoming home owners (the traditional route to prosperity), but have experienced a decade of wage stagnation and job insecurity, have turned their back on the idea of aspiration? And that a fashion industry that still often sells the trappings of last century’s upper classes (think exclusive social events, obscure equestrian sports, or impractical luggage designed for redundant methods of transport) needed to find a way to connect with a broad range of young consumers? If fashion labels have become too slick and luxurious, perhaps streetwear is the antidote.

Right up your street

The people featured in this story are not associated with and do not endorse

MR PORTER or the products shown