THE JOURNAL

In an era of fast fashion and over-hyped sneaker drops, craftsmanship and cultural heritage are often forgotten. But the world is changing, and many of us are developing a new appreciation for well-made, innovative clothing, the places it comes from and the people who make it. From ancient boro patchwork in Japan to crocheting in India and the upcycling movement, we take you on a tour of clothing crafts around the world.

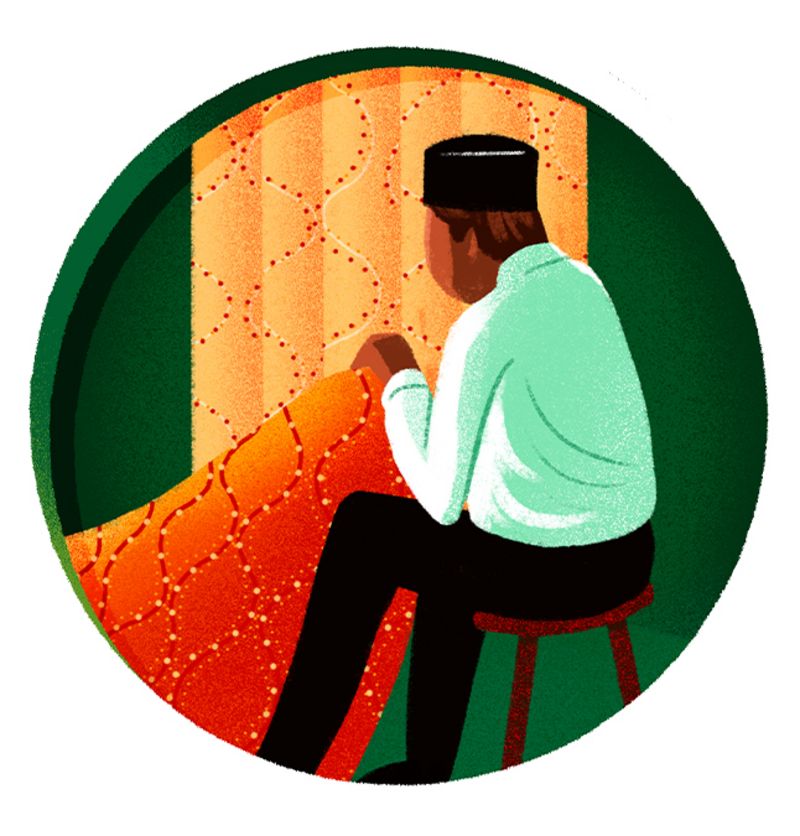

01. Japan: boro patchwork/sashiko stitching

Boro, which means ragged, has mixed connotations. It is revered in the West as one of the highest forms of textile craft. Pieces of antique boro textile can change hands for thousands of pounds. But this most exquisitely hand stitched and patched fabric, which is celebrated by brands including Blue Blue Japan, was once a symbol of poverty. Tiny scraps of fabric would be joined together and meticulously stitched using a technique called sashiko. This simple running stitch, usually in a contrasting natural thread, was traditionally used by rural Japanese in the 17th and 18th centuries to layer together lengths of locally indigo-dyed hemp as a form of quilting to add warmth. Cotton was scarce and expensive, so clothes would be passed down through the generations and repaired, stitched and patched. Ironically, in these times of over-consumption, when clothes are in plentiful supply, techniques borrowed from boro are a signifier that you care about craftsmanship and the longevity of your clothes. You might even invest in a sashiko needle and thread and try it yourself.

02. Indonesia: batik

The word batik comes from the Javanese word ambatik, which means a cloth made of little dots. Tiny dots of wax are applied to fabric, which is then dyed. The wax, applied either through a spout or stamped onto the fabric, resists the dye and leaves an intricate pattern. Traditionally, the fabric would be dyed using local plants such as indigo or the bark of the soga tree. Fine batik fabrics can take months to produce because they use a variety of colours and patterns.

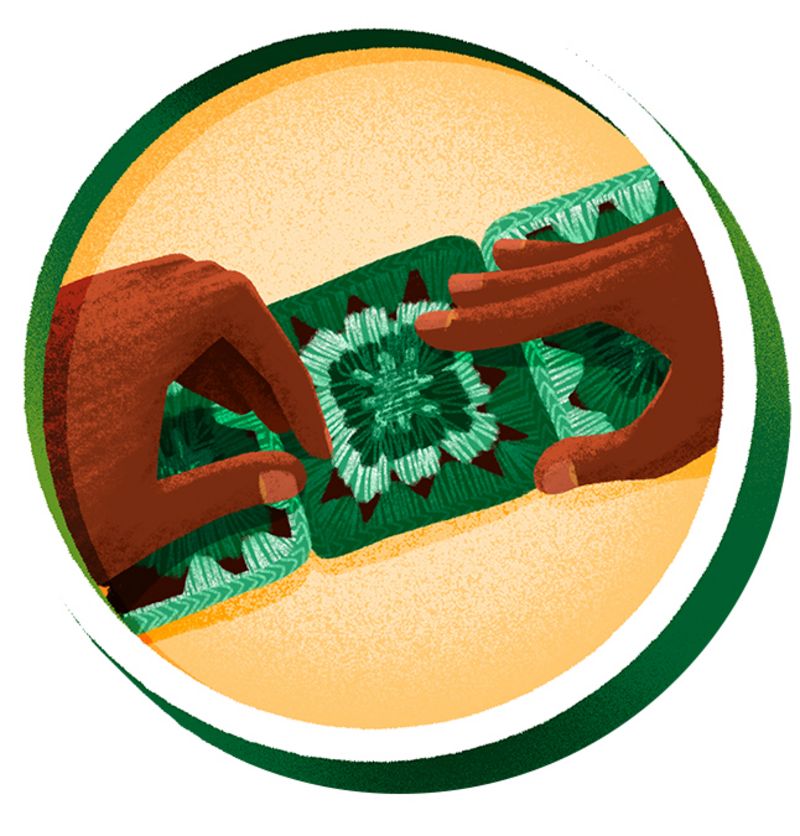

03. India: crochet

If you want proof that there’s more to crochet than your grandmother’s blanket, look no further than Story Mfg., which can’t resist incorporating a little square of it into its clothes. Crochet is thought to have been introduced to India by Scottish missionaries in the early 20th century. The familiar homely squares that embellish Story Mfg.’s clothes add warmth to more utilitarian garments and provide well-paid work for local communities. Each crochet square – incorporated as a stripe across a sweatshirt or a scarf – is made from organic cotton, hand-dyed using locally grown indigo, jackfruit and madder to create an earthy, moody colour palette, very different from the brightly coloured designs you might be familiar with.

04. India: khadi

In India, khadi (traditionally hand-spun and hand-woven cotton) represents political and economic independence. In the 1920s, Mahatma Gandhi encouraged people across India to boycott British imported cloth and instead to spin and weave their own. Khadi, which can be woven in various weights, is now seen as a luxury and the imperfections in the yarn and the weave are something to be celebrated. It has come to symbolise a more sustainable source of cotton, particularly if it is organically or regeneratively farmed. Today, many weaving cooperatives in India use the sun to power their looms.

05. US: upcycling

Upcycling – or making something new from something old – has been around for centuries. It’s only in the past 50 years or so that we haven’t looked after, mended and repurposed our possessions to make them last longer. But there is now a shift in fashion to use existing clothes as raw material for new collections. A new generation of designers is meticulously unpicking old garments, whether it’s jeans, sweatshirts or business shirts, and finding new ways of stitching and splicing them back together. Designers such as Greg Lauren in California have got it down to a fine art, creating hybrid items from used military clothing and old sportswear.

06. US: quilting

It’s interesting how patchwork quilts – traditionally the work of women – have become such a favourite resource for men’s clothing. Look no further than New York label BODE’s jacket, which is made from quilts from the 1800s and re-worked vintage clothes. Designer Ms Emily Bode tells stories with her clothes, using heritage techniques and nostalgic sentiments from the folk textile history in the US. Amish quilts, in particular, are known for their rhythmic, repetitive patterns and subtle use of solid blocks of colour, so it is no surprise that they are perfect for adding soul to a wardrobe. This celebration of the domestic, the delicious unevenness of the stitches, the feminine touch and the comfort of a quilt say much about the unstable times we live in. They provide a feeling of security and tranquillity when the world offers none.

07. France: lace-making

Lace originated in Italy, but it became popular in France during the reign of King Louis XIV. Men and women couldn’t get enough of the complex decorative patterns for cuffs and shirt collars. Who could blame them? If it was good enough for the king, it was an aspiration for all. In the early 1800s, the Leavers machine, which was invented in Nottingham, found its way to France. It allowed complicated lace patterns to be manufactured commercially using Jacquard cards. Lace-making was still a precious luxury, but it became a little more accessible. The tradition of lace-making continues in France and the very best is still made on those original machines.

08. Italy: tailoring

Tailoring is a craft often passed down through generations from father to son. In Italy, tailoring is looser and less structured than on Savile Row, more suited for the heat of a Naples day. But a lack of structure doesn’t mean a lack of rigour. There’s a fine art to cutting and understanding the way a fabric drapes and hangs. The craft of the Italian tailor is intertwined with an affinity with cloth from the country’s finest mills. Then it depends on years of apprenticeship to know just where to place a dart, how to ease a sleeve into the shoulder so there is room to move – so crucial to an Italian jacket – and the precise width of a lapel. Inside, without any lining to hide behind, the piping of a seam must be confidently finished to reveal a structure as perfect as a finely boned face.

09. Peru: pallay

Using alpaca or llama wool that is soft, warm and hypoallergenic, weaving has been part of the fabric of Peruvian society for millennia, and its rich and colourful designs are an inextricable part of the Quechua culture in the Andes mountains and beyond. From ponchos to carrying clothes for babies, the bright textiles are instantly recognisable, and the patterns and colours vary from region to region. As you might expect, the process hasn’t changed for centuries – after the animals are sheared and the wool is washed, the fibres are spun into threads using a drop-spindle. The practice remains close to nature. Yarns are dyed from native plants and insects and the looms are crafted from wood and bone.

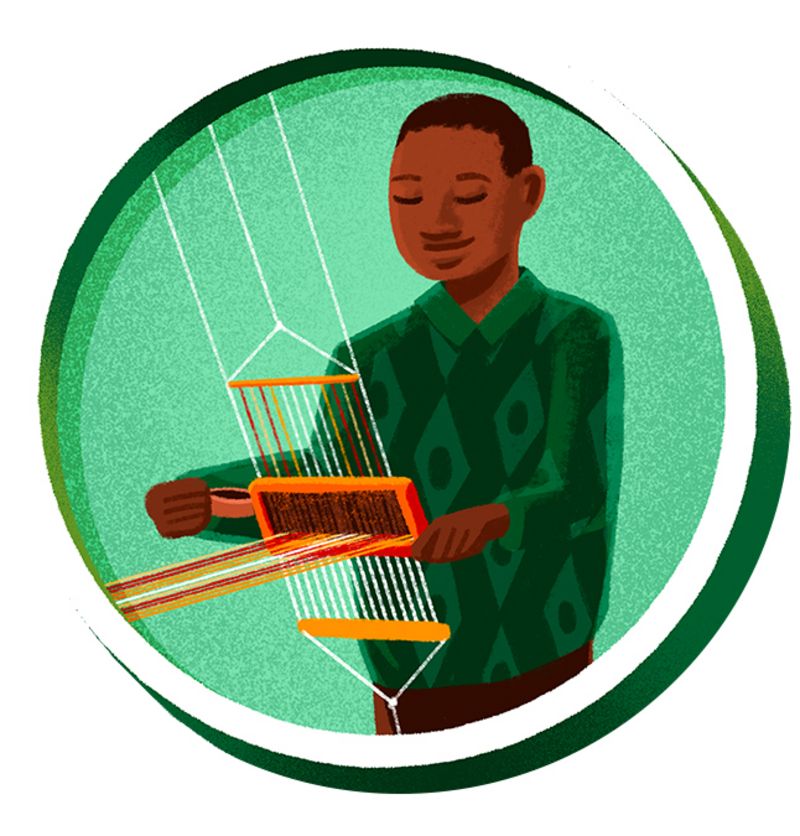

10. Nigeria: aso oke

Aso oke, which translates as “top cloth” in English, is a vibrant, patterned Yoruba fabric that was traditionally worn by the upper classes in Nigeria. The making process is notoriously longwinded and involves thinning the cotton through a spindle before it is sorted and cleaned. It is then woven into striking patterns on hand-operated looms. Woven and worn by men and women, the patterns today are endless, but traditionally consisted of a crimson colour known as alaari, a deep navy blue called etu and sanyan, a desert-coloured ecru. Of particular note is the aso oke hat, a type of fez that is known in Yoruba as a fila, which is crafted from velvet and cotton.

11. Worldwide: microbial weaving

The future could lie in biotechnology, growing bacteria into textiles. Material innovators, such as Ms Jen Keane, who recently completed an MA in material futures at Central Saint Martins, are pushing the frontiers of design, science, craft and technology. She weaves bacterial cellulose to create futuristic zero-waste sneakers that require no sewing or glue and can be grown into whatever shape is required. She weaves the warp and the bacteria grow the weft into the shape she has created. She’s using the most ancient and traditional of crafts, but taking a novel approach to the way we make – and grow – textiles and materials. New sneaker technology is also using ancient crafts such as knitting, but in ways that are sustainable and reduce waste.

Illustrations by Mr Sam Brewster