THE JOURNAL

Mr Himesh Patel is a sensitive soul. He wrestles and struggles with things. Not that you could tell from his career. The 31-year-old Brit is riding a wave. It started with him landing the lead in Mr Danny Boyle’s 2019 film _Yesterday _(about a hapless musician who co-opts The Beatles’ songbook). Mr Christopher Nolan’s Tenet followed. Now he’s starring in two of the most anticipated and timely projects on TV. His disposition (what Boyle calls a soulful melancholy) is probably what makes him such an engaging presence. He struggles so honestly, so movingly and at times so funnily (have you seen his neurotic comedian in Mr Armando Iannucci’s Avenue 5?), you can’t help but want to struggle along with him.

In his latest project, Station Eleven, an HBO Max mini-series based on the novel by Ms Emily St John Mandel, he’s got plenty to struggle against. It tells the story of a flu epidemic that devastates the world. Patel plays a survivor who spends the first 100 days holed up in an apartment with his brother and an eight-year-old child he’s rescued. Patel shot these episodes in early 2020, before the real pandemic hit, which must have been strange.

“Yeah,” he says. “It’s weird looking back. It probably meant I started taking the pandemic more seriously. I certainly had moments of fear early on, thinking, ‘What if this spirals?’”

He recalls shooting a scene in which his character pushes multiple supermarket trolleys loaded up with groceries. “That was the day my partner came to set,” he says. “She was looking at the trolleys full of random stuff like Lucky Charms and was like, ‘If this happened, this isn’t what you’d buy.’ I was like, ‘Whatever. It’s just a TV show.’”

Less than a month later, before the first lockdown in the UK, he recalls, “We were at home wondering if we should stick a food order in, before it goes mad. If we hadn’t had that conversation, I would’ve been like, ‘It’s going to be fine.’ But I knew it could not be fine. And, of course, it wasn’t. Thankfully, it didn’t get as bad as it does in our story.”

We’re meeting for coffee at a hotel in Soho, London, where Patel has turned up looking not dissimilar to his character in flight from Chicago midwinter. He’s wearing a big coat and bobble hat, a checked overshirt, dark jeans and boots and lugging around two hefty bags. It takes a minute or two for him to disrobe.

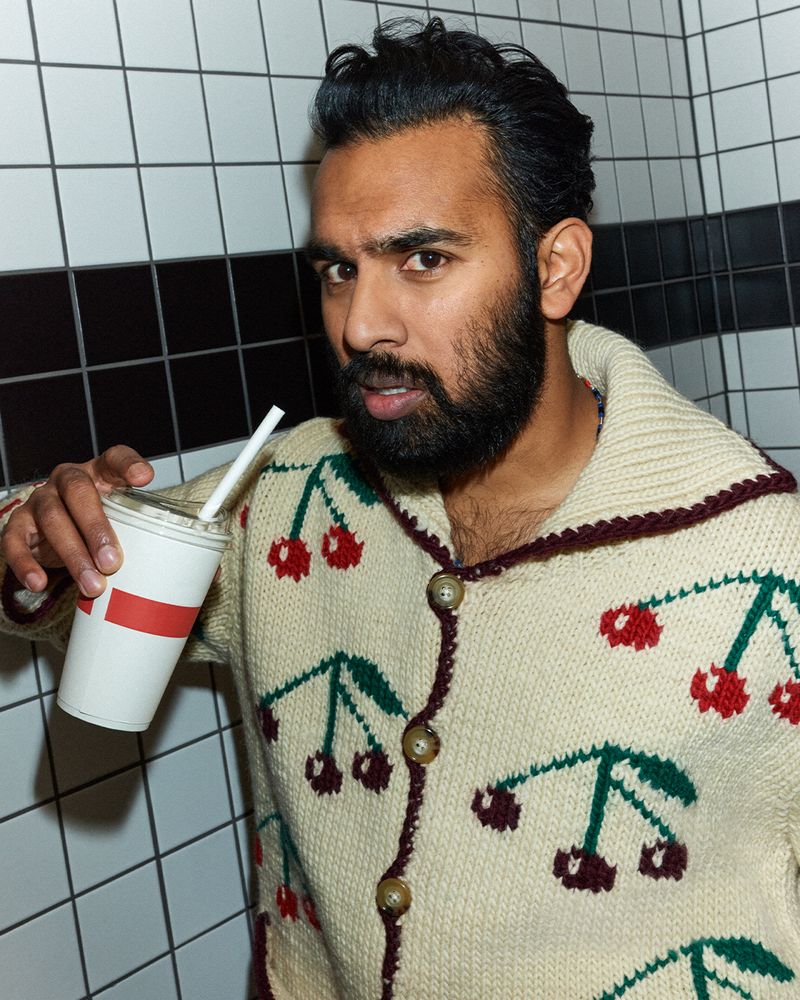

BODE Cherry Intarsia Merino Wool And Mohair-Blend Cardigan coming soon

As he goes on to explain, Station Eleven was prescient in other ways, too. In rescuing an eight-year-old child, his character effectively becomes a father, a role he struggles with. In real life, Patel also became a father.

“I wasn’t expecting to be,” he says. Between starting the show in January 2020 and returning to filming a year later after a Covid hiatus, “My entire outlook on life changed.” Playing those fatherly scenes, “There were definitely things I was drawing on,” he says, “but the difference for me was it was a choice I made and something I love.”

His daughter is now 12 months old. I ask if somehow Station Eleven ushered him towards fatherhood. “Almost certainly,” he says, “because there’s a practicality to being a parent. Can I afford this? Can I take care of this child? When Station Eleven came along, I’d finished Yesterday. I was shooting Tenet, but I didn’t know what was next. This job meant we’d be OK for a bit. My partner and I talked about having a baby and went, ‘OK, let’s dive in.’”

So without Station Eleven, he might not be a father? “Ultimately, it was an emotional decision, but coming from the background I come from [Patel grew up the son of two Indian newsagents in a small village in Cambridgeshire], there was this thing about how you can’t be led by your heart. It’s got to be practical as well.”

When his daughter was three weeks old, Patel flew to Boston to shoot his other new project, Netflix’s climate satire and likely Oscar contender Don’t Look Up, directed by Mr Adam McKay (The Big Short, Vice). Starring Mr Leonardo DiCaprio, Ms Jennifer Lawrence and a cast that includes Ms Cate Blanchett, Ms Meryl Streep and Mr Timothée Chalamet, it follows two astronomers who try to warn the world about a comet that will destroy Earth. Patel plays a supporting role as Lawrence’s boyfriend. One of the highlights was shooting an improvised scene on the street with Lawrence.

“One of the takes, I was basically escalating panic at Jennifer and I accidentally spat in her face,” he says. “She reacted well in the scene, but in the back of my mind I was going, ‘Shit! I just spat in Jennifer Lawrence’s face.’”

Given the calibre of these projects, I wonder if he feels a growing sense of momentum to his career. He answers uncertainly. Signing to US agents helped him land these parts, but he still feels unsure about aspects of the industry, such as self-promotion.

“I’ve been very hesitant to do that,” he says. “I’ve always had a fear of tipping over into arrogance. But what I’ve been reminded of by friends and loved ones is that that isn’t possible because I’m still so aware of where I’ve come from.”

Patel’s humble background comes up a lot. He worries about his Gujarati parents, who moved to England in the 1970s and continue to work long hours. “I’m trying to get them to slow down,” he says. “They worked to build their lives to give me and my sister opportunity. They succeeded. We’re both doing great.”

His sister, older by seven years, has a PhD in biochemistry and works at Cambridge University. “I want them to enjoy the fruits of their labour.”

Another mark of Patel’s upbringing is just how down to earth he remains. Not that he would call himself a fashion plate, but his biggest splurge on clothing has been a pair of Paul Smith shoes (bought from MR PORTER) for less than £400. Not nothing, but hardly a splurge. Last year, he purchased an Audi. “But that’s not a splurge,” he says. “It’s practical. Travelling with a child, it’s amazing the amount you need.”

The downside of coming from modest beginnings is what sounds to me like impostor syndrome or perhaps a reluctance to claim his due as a bona fide rising star. Being a socially awkward nerd may have something to do with it, too. Talking about the red carpet and figures such as Mr Billy Porter or Zendaya, who “own” it, he unsurely remarks, “There is such an ocean between the Met Gala and growing up in a newsagent’s in a village in Cambridgeshire.”

“I’ve always had a fear of tipping over into arrogance. But what I’ve been reminded of by friends and loved ones is that that isn’t possible because I’m still so aware of where I’ve come from”

Landing a role aged 16 on TV soap EastEnders, a national institution in Britain, may have been his break (he spent nine years on the show), but it also entrenched the idea that somehow he should feel grateful and certainly never raise concerns about the depiction of his character (a Muslim geek called Tamwar Masood) if he had any. “I was a little kid from a little village,” he says. “I never expected to be on national TV. Not at that age. You just don’t want to put a foot wrong or them to take it away from you. I never felt like I wanted to stick my neck out and cause trouble.”

The example he gives is not about Tamwar’s depiction as a Muslim – the show has been criticised for having stereotypical Asian characters – but about Tamwar suddenly doing impressions of other characters and wanting to become a stand-up comedian, a storyline based solely on Patel’s deadpan style as an actor. “I remember it jarred with me,” he says. “But I was too young to go, ‘I’m not going to do that.’”

The randomness of the plotline underlined how marginal he was in the scheme of things. “There is a hierarchy of people who have been there a long time and have a lot more of a say in things – characters who are ‘more important’. I never felt like I was important enough.”

Leaving the show was “step one” towards reclaiming “a sense of empowerment”, he says. He was glad Tamwar got a happy ending and wasn’t bumped off in an explosion or car crash. The character left and married his girlfriend, Nancy, in Australia. When Nancy returned to the show earlier this year, however, it turned out not to be such a happy ending. She was divorced. “It was funny,” says Patel. “He’s got his own life now, living in that world somewhere, newly divorced. I wish him well.”

Growing up in a community with so few brown faces also took its toll on Patel as a kid. He talks about the effects of structural racism, which he only fully comprehended when he moved to London, aged 21, and met other British Asians who’d experienced the same. The example he gives sounds minor, but is it?

“The disconnect of cultural references. Bollywood. Nitin Sawhney albums. No one at school was interested. Instead of other pupils going, ‘Cool, that’s interesting, tell me about it,’ it was like, ‘I don’t care. It’s not relevant to us.’ I couldn’t articulate it at the time, but I guess I felt othered, ostracised. That’s actually quite a difficult thing to go through. You’re basically being told this entire part of your identity is meaningless. I realised recently it might have dampened my creative spirit.”

Because I’m British Asian and have been called “Patel” (among other Indian names that are not mine) enough times, I grasp the significance of what he tells me about being in professional scenarios where people should know his name, but he has been identified as “Hamish” on multiple occasions.

“If we go back to these things I was going through as a kid, which I laughed off because it was a survival thing, you realise how much you’ve done as a survival mechanism,” he says. “Especially as a minority growing up in a very minority situation. I’ll laugh it off, because where am I going to turn with this feeling? But now I go, ‘I’m not going to just put up with it because it needs to change.’ It comes back to sticking your neck out. Sometimes there is more than one of us on a show. We don’t all have the same name. We’re not all related. Please learn how to say my name. Is that too much to ask?”

It doesn’t surprise me from the way Patel talks about himself (with careful, bruised introspection) that he sees a therapist. “I started going not long after moving to London,” he says. “It has definitely helped [me express myself].” It comes up when we’re discussing an award-winning short film called _Enjoy _(now doing the festival circuit), in which Patel plays a tutor suffering from depression. I wonder if he’s had any experience of that, not necessarily meaning directly.

“Yes, I’ve had personal experience of struggles with aspects of mental health,” he says. “And I will continue to, because that’s what it is. What I had initially in my head was: there is a problem, eventually I will solve it. That can be the case for specific things, but certain stuff is just work you have to do and I’m still learning how to do that work and make time for that in my day. I think what depression can do and, in my case, certainly has done is stop you believing in people around you. You believe so little in yourself, you don’t believe anyone else would want to hear, so it takes a step to then express that anxiety or fear to your best mate or partner.”

I ask how comfortable he is talking about this publicly. Again his upbringing comes up, but this time as a powerful motivating force. “I’m never going to be the type of person who gets into my private stuff,” he says. “But I often remind myself I grew up in a little village. My parents have a newsagents. My window onto actors I admired were the interviews they did. For me growing up, I just wanted to feel a sense of recognition. There is a false perception, especially in the male world, that talking about mental health is a weakness. I don’t want to not talk about my struggles with mental health because if there is someone who wants to read an interview with me, a young brown actor or whatever, it’s not a weakness to be struggling with this. It doesn’t stop you from doing what you want to do. It’s good to put that on the table and say, ‘Hi, I’m an actor, but I’m also a person. I have my struggles with mental health and that’s not a problem.’”

Don’t Look Up is available to stream on Netflix from 24 December; Station Eleven arrives on HBO Max on 16 December