THE JOURNAL

Two Oscars, three languages and zero tolerance for BS. Just what is Hollywood’s most notorious villain like in real life? .

“Frosty”, “evasive”, “taciturn”, “terrifying”, “extraordinarily intelligent” with “a steel rod at his core”. These are just some of the words and phrases used by survivors of an interview with Mr Christoph Waltz. (Later, he himself happily adds “misanthropic” to the list.) In the Mr Robert De Niro-esque tradition of actors unwilling to modify themselves to play the game, Mr Waltz has upped the ante of The Impossible Interview, precision-delivered with wordplay, mind games and what appears to be a subtle understanding of the psychology of menace.

And he should know. The Austrian-German’s roles include a raft of dastardly Euro-villains, from the passive-aggressive Jew hunter Colonel Hans Landa in Mr Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, to the Greek-Polish Franz Oberhauser (aka Ernst Stavro Blofeld) in Spectre, by way of Russian gangster Benjamin Chudofsky (The Green Hornet) and Leon Rom, corrupt Belgian envoy to King Leopold (The Legend Of Tarzan).

To date, no journalist has torched through the iron curtain the Viennese actor has imposed on his private and internal lives. (“I don’t have an iron curtain. I have a plumb line,” he later corrects me.) This is partly, I suspect, because, as a gifted linguist, he may be unbeatable in a duel of words. I also have a hunch that he is an unscrupulous liar. “Unflinching,” he concedes, fixing me with his husky-ish eyes. “I never use the word ‘truth’. We use ‘true, true story, the truth’ very foolhardily and carelessly.” (In the run-up to the release of Spectre, he repeatedly stated that he was “definitely not” Blofeld.) All this makes Mr Waltz as uncrackable as a double agent, and the promise of a battle of Waltzian wit and will rather thrilling.

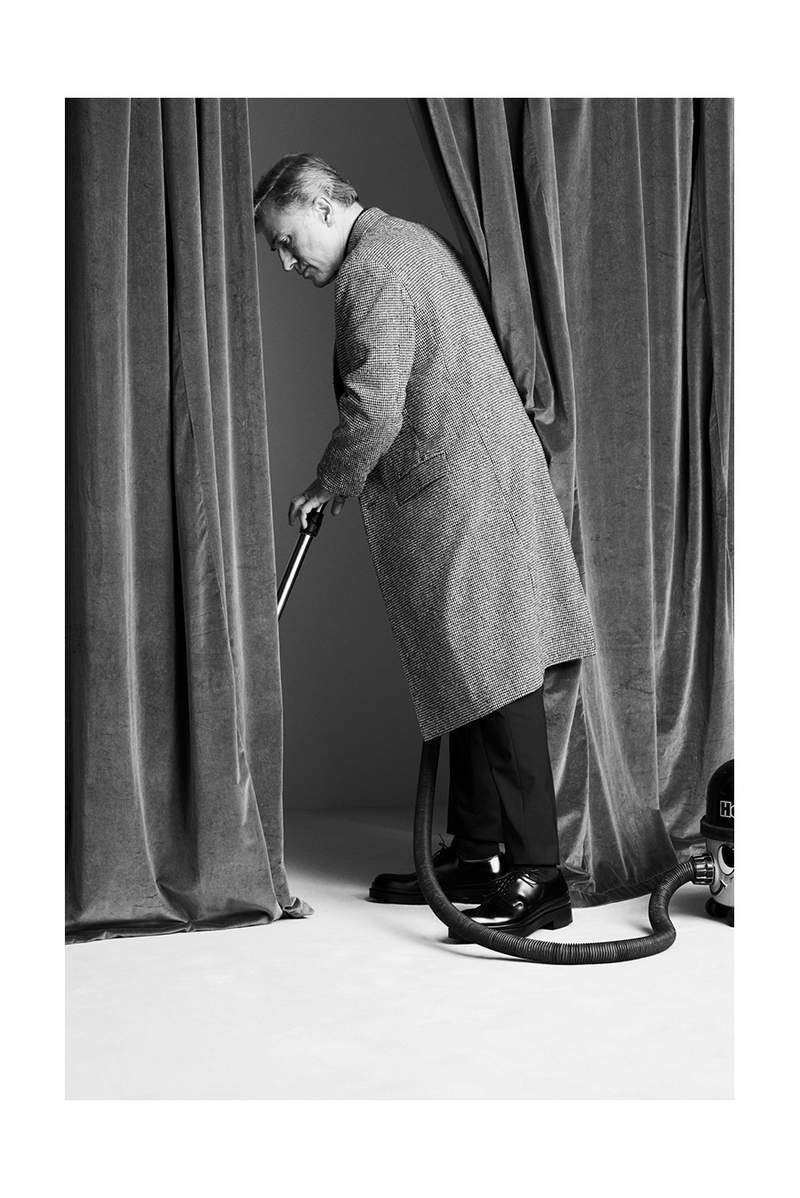

I can’t help feeling like a proverbial lamb to the schlachter, as I trot through the Christmas ersatz, blur and bustle to his London hotel. By contrast, in his suite, everything about Mr Waltz is crisp and almost surgically en pointe, from the exactitude of his language, his sentences cleft by a scalpel-sharp mind, to his immaculately laundered attire. “I always dream about a closet that has 10 suits, all identical. In dark blue. All handmade, exactly how I like them.” He manages to make this sound vaguely threatening. “My friends at Prada now make a deconstructed shoulder, which is exactly my cup of tea.” With 10 identical pairs of Rudolf Scheer & Söhne shoes? The Lobb of Vienna, I venture sloppily. I am swiftly corrected. “Nice shoes, but the Lobb last is a completely different cut.”

All this is made charming by Mr Waltz’s old-world Mittel-European manner – upon my arrival, he takes my coat and pulls back a chair for me to sit down – and the fact that he commands rather than speaks English. He also commands German and French. The total effect is rather like entering something between a Viennese literary salon and a consultant’s waiting room. But it is not long before I warm to him. For all his doctorly detachment, Mr Waltz is courteous and hyper-attentive, processing questions at lightning speed, referencing a choice of word I made 15 minutes before. I rather appreciate his exacting intellect and, despite digressions on the forgotten proletariat of imperial Vienna, I find him neither pompous nor pretentious. There are moments when he could even be described as good-natured.

Mr Waltz veers from verbal austerity – refreshingly at odds with the tattle and blabber of the chatosphere – to pouring forth metaphorical flourishes, even if some seem to be an evasion tactic. Ask him the appeal of his upcoming film, Downsizing, and he answers, “There is never one thing, just like with beautiful ladies. You say, ‘Is it the red hair?’ No. I mean, of course it’s the red hair. I love red hair. But if there is no spirit behind, if there is no sense of humour, if there’s no mystery…” It’s just that he dislikes any statement that might lead to a generalisation. “If one throws everything in one pot all the time, then what one gets is one general brown soup that doesn’t apply to anything.”

For Mr Waltz, it is all about precise “details”. In his roles, it’s “the only thing that matters. Because the accumulation of details is what gives a result.” If there is anything frightening about Mr Waltz it is perhaps the extent to which he appears to be ruled by logic. “Common sense? Well, that’s something that’s completely gone out of fashion, hasn’t it?” It is no surprise, then, that he does not subscribe to method acting, despite his exemplar being Mr Robert De Niro. “If an actor feels he has to live in the desert for half a year and live off eating lizards, then so be it,” he says when we discuss Mr De Niro’s legendary weight gain for Raging Bull. “It’s probably the one thing I would criticise De Niro for. What difference did it make? What you get from it is: ‘Look at how fat De Niro is. Wow, he must have really eaten a lot.’ Great.”

Mr Waltz is opinionated, yes, and wonderfully so in the anodyne milieu of the contemporary interview. At one point, I think he might even be enjoying himself. I am privy to a few impish grins. For all his Teutonic debonair and formality, there is something rather boyish about Mr Waltz, reminiscent of a young and better proportioned Mr Gérard Depardieu. At 61 going on 41, it is as if no wrinkle would dare to sully him. Rather useful for a man whose Hollywood career began at the age of 53.

All of this made Mr Waltz perhaps the only actor equipped to step into the jackboots of the trilingual Colonel Hans Landa, a man who uses eloquence and civility as weapons, and can terrorise with his apple strudel-eating etiquette. Mr Tarantino feared that, in Landa, he had written a character who was unplayable. The story goes that he was hours away from abandoning his script for Inglourious Basterds. Then, in a last-chance-saloon audition in Berlin in 2008, Mr Waltz, an actor frustrated by a 30-year career in German television, walked in. He spoke Landa’s baroque dialogue “like a Stradivarius”. In 2009, Mr Waltz won 29 awards, including an Oscar, a Golden Globe and a Bafta for his performance. Upon receiving the first at Cannes, he tearfully thanked the director for giving him back “his vocation”.

But one might question who saved whom? As Dr King Shultz, a German dentist turned bounty hunter, he also carried Django Unchained, considered to be Mr Tarantino’s comeback film. (The director wrote the role especially for him.) Mr Waltz won a second Academy Award and Hollywood was awarded a character actor who, with seemingly unlimited on-screen nationality, was almost too good for it. Mr Terry Gilliam’s The Zero Theorem (2013) – the third instalment of the director’s “Orwellian triptych”, following 1985’s Brazil and 1995’s 12 Monkeys – was only given the green light once Mr Waltz had signed up. Since then, as if by karmic boomerang, he has had his pick of cult directors to work with, from Mr Roman Polanski (Carnage, 2011) to Mr Tim Burton (Big Eyes, 2014).

In Downsizing, from Sideways director Mr Alexander Payne, Mr Waltz plays a 2in-tall Serbian playboy opposite Mr Matt Damon’s 2in-tall lead. The premise of the dystopian comic satire is a scientific breakthrough that offers a solution to Earth’s impending apocalypse. Shrink human beings and therefore their consumption of diminishing resources. But human nature has an undiminishing capacity to spoil a good thing. Is Mr Waltz a misanthrope? “Oh totally,” he says. “I really find people despicable.” He’s not an environmental optimist either. “It’s over, I tell you. There’s not a speck of land on the globe any more that is beautiful, magic. The only place one could go possibly is North Korea.”

Mr Payne’s films often frame a male mid-life crisis. Pre-Inglourious Basterds, Mr Waltz was in his own last-chance saloon, ready to give up on his Hollywood ambitions after three decades of critically acclaimed pan-European dramas and satires, but no big break. Did he ever feel a sense of failure? “Yes, constantly,” he says. “But just because it wasn’t Tarantino doesn’t mean that everything I did before was worthless.” Indeed. By the time of that Berlin audition, he had reached an impasse. “I needed to remove a blockage,” he says. “I was at a point where a quantum leap, which turned into a Quentin leap, was required.”

He won’t expand on the exact nature of this blockage or whether it was self-induced. Does he believe in psychoanalysis? His grandfather, Dr Rudolph Von Urban, was a student of Mr Sigmund Freud and wrote one of the first self-help books, Sexual Perfection And Marital Happiness. “I don’t believe in psychoanalysis as a cure, but as a discovery of oneself,” he says. Has he had therapy? “Not analysis and I wouldn’t, no.” I’m not sure I believe him. His first wife, whom he married in his early twenties, was a psychotherapist. It cannot have helped his thespian dreams that he had three young children to support, explaining Austrian police drama Kommissar Rex, in which he played second fiddle to a dog, on his CV.

Mr Waltz never wanted to be an actor. The fifth generation of a Viennese theatrical family – his German father and Austrian mother were a set and costume designer respectively – he found thespian talk around the dinner table, “stifling”. His upbringing was “very bourgeois” and his parents “rather settled in their social function as a theatre family”. He found Vienna in the 1960s restrictive. “It was very close to the Iron Curtain,” he says. “The facades were rotting off the buildings. It had its own magic, but it wasn’t something that a 15-year-old could appreciate.” Did he rebel? “Not loudly. I just did my own thing.”

He originally wanted to be an opera singer. (These days, Mr Waltz, a baritone, is limited to singing around the house. He has a newfound love of Mr Giacomo Puccini.) But a shift occurred around the time of seeing Mr Peter Brook’s landmark Royal Shakespeare Company production of A Midsummer’s Night Dream when it was on tour in 1970. “It was an eye-opener to such a degree that I thought, now for the first time I’ve seen theatre,” he says. After studying at the Max Reinhardt Seminar in Vienna, in his early twenties he moved to New York, the epicentre of 1970s filmmaking. “I saw Apocalypse Now when it came out,” he says. “I saw the first Godfather. In New York. At the [iconic] Zeigfeld Theatre. On the big screen. I felt myself a child of that time.”

He agrees that this timing raised his career expectations. “Of course,” he says. “I’m glad it was not later. The difference between those movies and those made today – it’s not two different eras, it’s two different worlds.” He was “fascinated” by Mr Marlon Brando, Mr Oskar Werner, the Austrian muse of Mr François Truffaut who crossed over into Hollywood, and, above all, Mr De Niro, for whom his admiration has never waned. “Even with the [films he does now], which are criticised for being beneath him, that’s where you can tell that someone is truly great. Yes, it’s schlock. But De Niro is still De Niro.” Mr Waltz studied under Mr Lee Strasberg and Ms Stella Adler, waited on tables in a Greek-owned restaurant, but failed to break into Hollywood. What if an Oscar had landed in his lap at 23 instead of 53? “Well, the plumb line might have been more of a pendulum,” he says. “It’s not that these drugs aren’t available any more, but it takes about a day and a half to corrupt a kid on a movie set.”

He returned to Europe and worked on the stage in Vienna, Zurich and Salzburg, before moving to Muswell Hill in London in 1988, where he couldn’t land a part in a Shakespearean production for love nor money. He pleaded with Mr Peter Wood to let him play Caliban in The Tempest. But it was argued that even the native of a remote island should have a British accent. “Just because Shakespeare was English, it doesn’t mean, at all, that the English are the only ones who can do it,” he says. “Some of the worst Shakespeare I’ve ever seen was in this town. Productions that provincial theatres in Germany would be ashamed to put on a stage, I’ve seen in the West End, hailed. I saw a production of The Merchant of Venice 20 years after A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It was like, they think they own it and they pissed it away.”

In the late 1990s, he moved to Berlin with his new partner, costume designer Ms Judith Holste, and 10 years later came the quantum leap of his career. It was as if all the awards denied him for three decades came at once, but with them came a lack of anonymity that still irks him. He has had to reconcile himself to the fact that, these days, recognition and fame are Siamese twins.

Mr Waltz divides his time between Berlin, London and Los Angeles. I expect a diatribe on, like, Los Angelino millennial-speak, but he’s surprisingly measured. “It’s gruesome,” he says. “But there are some Americanisms that have such an efficiency of communication. It’s proper English, just leaner. When you open a paper in England, you can almost hear the hot potatoes in their mouths.” Mr Waltz practises his own linguistic economy on the subject of Mr Harvey Weinstein, Mr Tarantino’s long-time collaborator. “I don’t think my contribution or opinion about intolerable behaviour is in any way required,” he says.

He’s playfully incensed when I suggest that in the post-Weinstein era a female Bond might have some merit. “Why? Because [Italian feminist journalist] Oriana Fallaci said so? Come on. Have your own movie if you want. Why does it have to be James Bond? What would be her first name? Jemima? My answer is decidedly not.” Despite rumours, Mr Waltz denies involvement in the next two Bond instalments. (I direct your attention to the above caveat.) And Reykjavik, based on the 1986 US-Soviet peace summit, in which he was cast as Mr Mikhail Gorbachev, has been shelved. “The idea of me playing Gorbachev, in a fat suit with purple make-up on the forehead, was, in a way, preposterous,” he says.

Much anticipated, however, is his Hollywood directorial debut Georgetown, based on the murder of a 91-year-old Washington socialite (Ms Vanessa Redgrave) by her second husband (Mr Waltz). I shudder to think how intimidating he must be in the director’s chair. “I’m too lenient,” he says. I don’t believe a word, I say. I bet he is petrifying. “Seriously, I know the actor’s plight. I’m too forgiving. Not demanding enough.” After a protracted stare, he flashes me a dentist’s grin. And he doesn’t even flinch.

Downsizing is out in January