THE JOURNAL

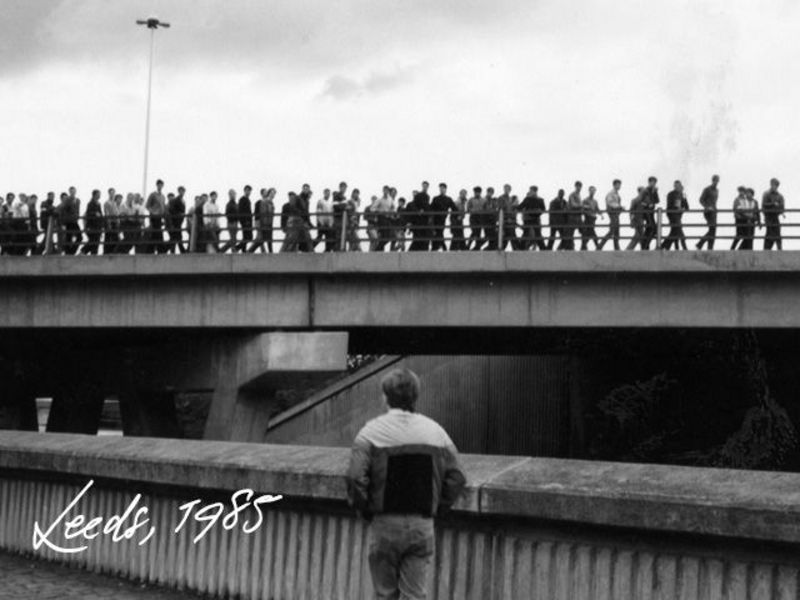

The tribe effect: Sheffield United fans walking through Beeston to an away game against Leeds United at Elland Road, Leeds, mid-1980s Courtesy Wuggie

Saturday lunchtime in a suburb of south London, spring of 1985. A residential side street, terraced houses, parked cars, kids on bikes. Sleepy, peaceful, boring. Then, in the distance, the sound of some sort of rhythmic chanting: alien, menacing, slowly building in volume and ferocity. Suddenly, around the corner march an army of young men, their faces contorted into expressions somewhere between ecstasy and rage. And the only thing you can think of, heart pounding, before pedalling your BMX in the opposite direction as fast as you possibly can, is: where on earth did they get those fantastic clothes?

The drawbacks of being a style-obsessed British adolescent in the mid-1980s were many: sweatbands, slogan T-shirts, Goth hair. But none was scarier than the stark truth that if you liked football and clothes – and we did, of course – you were almost constantly in awe of the dress sense of men who terrified you. Hard, violent, unpredictable men. Men who could spit further than you could run. These were the “casuals”, obsessive label hounds with a particular penchant for hard-to-find Italian sportswear – Sergio Tacchini, Ellesse, Fila, Kappa, later Stone Island and C.P. Company – as well as for limited-edition adidas trainers (never referred to as sneakers) and iconic British brands ripe for reinterpretation: Aquascutum, Pringle, Burberry.

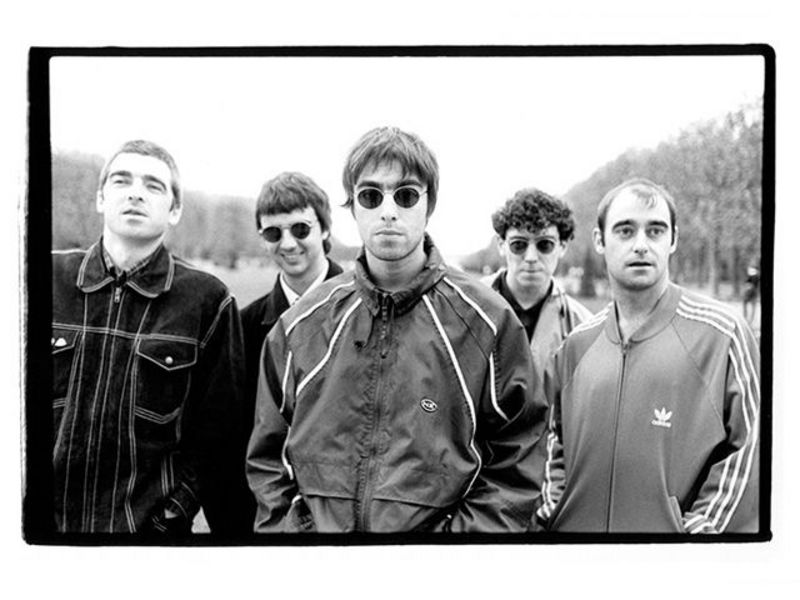

Oasis, from left: Messrs Noel Gallagher, Paul McGuigan, Liam Gallagher, Tony McCarroll and Paul "Bonehead" Arthurs in France, mid-1990s Renaud Monfourny/ Retna Pictures

The casual is the least storied and yet arguably the most influential tribe in the history of British street style. Punks, teddy boys, mods, rockers, soul boys, skinheads, ravers: all from time to time are fêted for their (sometimes rather limited) contributions to mainstream men’s fashion, but casuals are little known and often forgotten. There was no music scene to accompany their look and they were not as widely photographed or championed in the press. There was nothing cuddly about casual.

But if you’ve ever worn tennis shoes for a purpose other than tennis, or a cardigan over a polo shirt, or a waterproof kagoul when it didn’t look like rain, then for better or worse you owe a debt to the casuals. Just as hip-hop introduced the idea of high-end sportswear as a fashion statement to urban America, so casual – at almost exactly the same moment – did the same for Britain and, ultimately, Europe, the style incubator beyond. Overnight, leisurewear became a competitive sport.

Now it is back, yet it is one of today’s most pervasive yet unseen forces in menswear, whether you’re a “cool dad” unleashing your inner hoodlum by watching a child’s rugby match in retro sneakers, or whether you’re a member of the fashion industrial complex parsing a catwalk show in a kagoul. Mr Raf Simons has put his name to a limited-edition pair of Stan Smiths. Mr Giles Deacon sent Ms Edie Campbell down the catwalk in a pair of Gazelles. Marc Jacobs is a veteran adidas aficionado.

The origins of casual

The origins of the casual are disputed. Indeed, the term itself is the cause of disagreement. The writer Mr Kevin Sampson – he published arguably the first mainstream journalism on the movement with an article in The Face in 1983; and later the bestselling novel Awaydays – tells me that casual is a London term. In his home city of Liverpool the style’s proponents were called scallies, while in Manchester they were Perry boys. Either way, there was nothing casual about any of them.

“The term casual has to be the least apt label for a youth subculture ever,” says Mr Sampson. “The last thing you could say about the movement was that it was in any way sloppy or casual. It was fastidious and continually changing.”

This thing of ours

Mr Anthony Teasdale, another former scally and now a journalist and the editor of Umbrella magazine, has written widely on casual. He argues that the most apt name for the movement now is no name at all, but rather the enigmatic “This thing of ours”: a you-get-it-if-you-get-it catch-all to describe the shared sartorial codes of clued-up British men born since the 1960s.

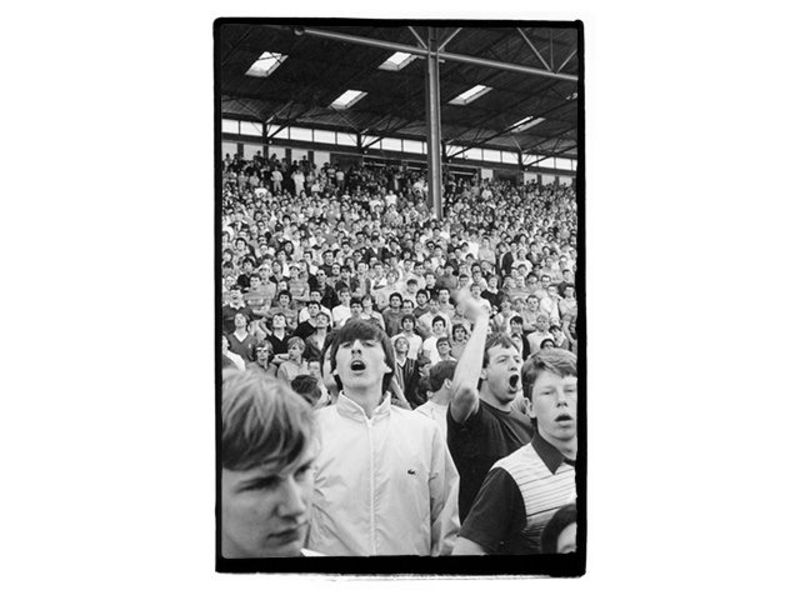

Football fans on Chelsea FC's old West Stand at Stamford Bridge, circa 1985, London © Jon Ingledew/ PYMCA

Nomenclature aside, all agree that the style was developed in the late 1970s among members of English and Scottish football firms: gangs of marauding fans who had previously dressed, in Mr Teasdale’s words, “like the Bee Gees: scoop neck jumpers, flares, big dry hair”, or perhaps in the uniform of the skinhead – MA-1 flight or donkey jacket, Levi’s Sta-Prest, Dr Martens bovver boots, shaved heads – but who now cultivated a smarter, more streamlined appearance. In some takes on casual history this look was adopted to evade detection by the police, but Mr Teasdale says this sounds like wisdom after fact. As the inheritors of mod – slogan: “clean living under difficult circumstances” – casuals were, he argues, simply doing what generations of working-class British men had done before: smartening themselves up for the weekend. In Mr Teasdale’s telling, the mod revivalists of the late 1970s became the logo-wearing lads of the 1980s.

Where it all began

Not all casuals were football hooligans and not all football hooligans were casuals, but certainly the football terraces of Europe were the casual catwalk. Liverpool FC were Europe’s dominant club and their most devoted fans followed them on to the continent, where they found shops selling sportswear unavailable in the UK. Mr Teasdale dates the birth of the movement to a specific game: Saint-Étienne vs Liverpool on 2 March 1977 in France’s Loire area.

Early casual styles included diamond-patterned golf jumpers from Lyle & Scott and Slazenger over Fred Perry or Lacoste polo shirts, and Farah or Lois slacks. Later, thanks to the unlikely style icons Messrs Björn Borg and John McEnroe, then in their Wimbledon pomp, came the obscure Italian sportswear labels. adidas was generally the preferred footwear, the harder to find the better: Samba, Forest Hills, Munchen, Gazelle, Stan Smith, Trimm-Trab.

A reveller at club night Deviation in Shoreditch's XOYO, London, 2013 © Teddy Fitzhugh/ PYMCA

Casual goes mainstream

The haircut was the wedge: short at the back and sides and long over one eye, necessitating a twitchy and somewhat effete flicking of the head to see properly. The style was reportedly pioneered by the hairdresser Mr Trevor Sorbie and modelled on the cover of Mr David Bowie’s Low LP, neither man presumably imagining they would inspire the tonsorial taste of a generation of troublemaking football fans.

Casual constantly changed. “Last week’s must-have was this week’s laughing stock,” remembers Mr Sampson. In London, casual came to mean pastel-coloured polo shirts accessorised with gold necklaces and sovereign rings. Up north, fans in Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds and beyond began turning up to football matches in tweed jackets and Sherlock Holmes-style deerstalker hats, a reaction against the trend for sportswear, which had gone overground. Mr Teasdale remembers in 1984 briefly forsaking his adidas sneakers for Hush Puppies.

Casual didn’t die, but it was much reduced by the late 1980s. While the disease of football hooliganism spread abroad, British firms, it is often argued, were mostly neutralised by a government crackdown on violence in the wake of a number of football ground disasters, and by acid house; it’s hard to want to punch someone when you’re both on ecstasy.

The baggier aesthetic of the Madchester scene and of the British rave and club culture that dominated the early 1990s returned casual to the margins, where you could see it in suburban lads who favoured expensive Italian leisurewear, particularly that designed by Mr Massimo Osti for Stone Island and C.P. Company. Reebok Classics replaced adidas; Paul Smith replaced Pringle. Younger tearaways – somewhat less imaginatively than their elder brothers – switched allegiance from limited-edition obscurantism to fashion megabrands, including Polo Ralph Lauren and Emporio Armani. New, home-grown labels – crucially, The “Duffer” of St. George – began to cater to retired casuals.

In somewhat diluted form, then, casual conquered the mainstream. The Britpop wars of the mid-1990s lined up the adidas‘n’anorak-wearing, northern working-class Gallagher brothers of Oasis against the mod revivalist, tracksuit top-sporting middle-class southerners, Blur.

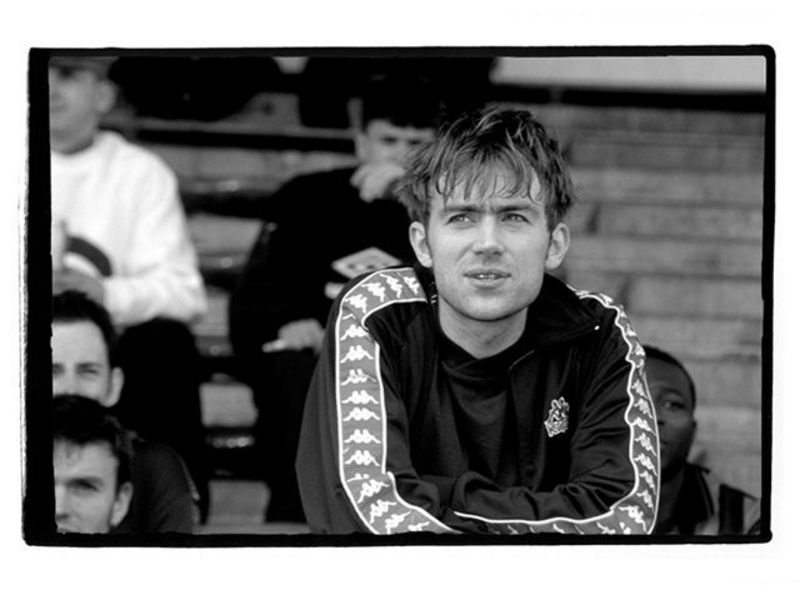

Mr Damon Albarn at a music industry celebrity football match, Mile End Stadium, London, 1996 Brian Rasic/ Rex Features

Club kids wore Fila hiking shoes and Duffer polo shirts. Indie kids wore Fred Perry and Farah. UK garage kids wore Umbro and Nike. And the pervasive lad culture of the 1990s and early noughties gave rise to a slightly dubious cottage industry of books (the memoirs of the former West Ham hooligan Mr Cass Pennant) and films (the oeuvre of casual’s auteur, Mr Nick Love) celebrating the exploits of early 1980s, fashion-obsessed football firms.

Today the legacy of the causal is an unseen hand on the high street and high fashion. A story in the current, pre-fall issue of i-D magazine heralds “a fresh wave of lad culture washing over London” – suggesting that switched-on young men in the British capital are mixing “Astrid [Andersen] with adidas, Nasir [Mazhar] with Nike, Raf [Simons] with Reebok and Christopher [Shannon] with Stone Island”.

How widespread that is I’m not sure, but on my walk to work this morning I passed a representative London sight: a stocky young man, early twenties, smoking like he meant it, in the sunshine outside a Pret A Manger. He was wearing a lightweight, faded blue Stone Island jacket in some sort of technical fabric over a Lyle & Scott polo shirt, baggy Patagonia shorts and a box-fresh pair of blue and orange Nike Huaraches. On his head, a navy Ellesse bucket hat, the likes of which I’ve not seen since 1988. I would have approached to ask where he’d found it, but – quite frankly – he was far too intimidating to talk to. Sign of a true British casual.