THE JOURNAL

Los Angeles, c. 1960. Photograph by Mr Robert Anzell/Everett Collection/Alamy

MR PORTER celebrates the actor, photographer and all-round phenomenon who made 1960s LA so much fun .

Way back in 1959, Mr Dennis Hopper’s PR agency issued a press release about him that was somewhat different from the standard studio-puffery of the time: “When he isn’t working,” it read, “Dennis rises at about 10 o’clock, reads Nietzsche (and other modern plays) poolside at his Hollywood apartment, visits art galleries, browses in bookshops and attends foreign films. He’s intense about everything he does.”

How right they were. Mr Hopper’s acting career spanned five decades, during which he went from starring alongside Mr James Dean and Ms Elizabeth Taylor to working with Messrs Andy Warhol and Quentin Tarantino, and even cameo-ing in Grand Theft Auto, all the while turning up his intensity levels, both onscreen and off, to at least 11 and a half. He kick-started a new Hollywood era at the end of the 1960s with the biker fantasia Easy Rider, brought terror to the suburbia of the mid-1980s as a gas-guzzling maniac in Mr David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, and was raising hell right up to his death from cancer eight years ago at the age of 74.

“There are moments that I’ve had some real brilliance, you know,” he reflected shortly before his death, “and sometimes, in a career, moments are enough.” (Such moments encouraged his daughter Ms Marin Hopper to create Hopper, a selection of carefully curated photography and style and art items that best capture her father’s legacy.)

Below, in honour of the new Mr Hopper-inspired collection from our in-house brand Mr P., we celebrate the ineffable personal style of the man The New York Times called a “world-class burnout, first-rate survivor”. Scroll down to discover eight ways to throw caution to the wind – that is, to be just a little more Mr Hopper.

GO WEST, YOUNG MAN

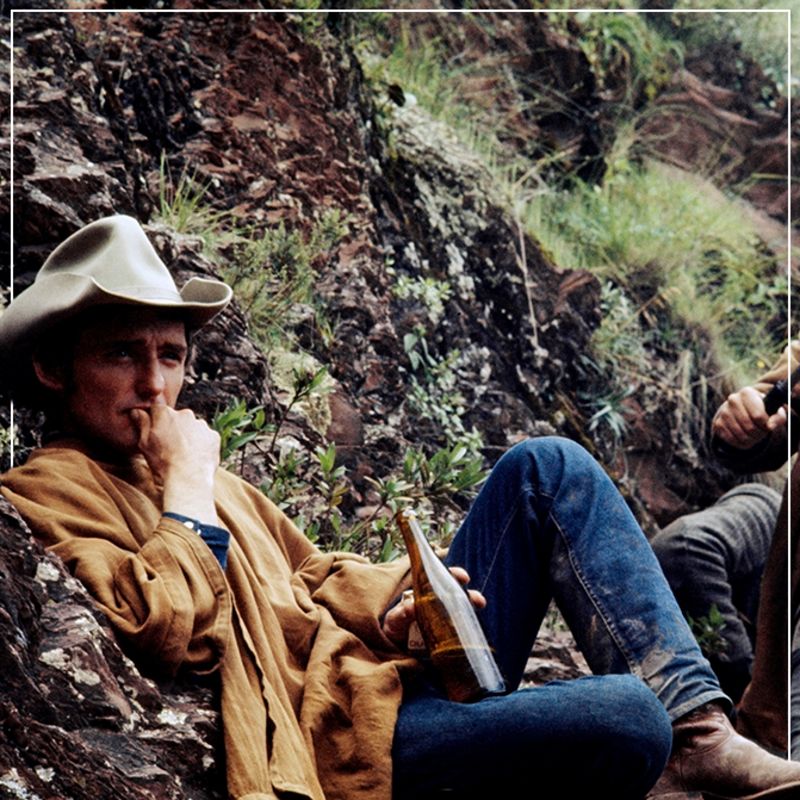

Filming The Last Movie, Peru, 1970. Photograph by Mr Dennis Stock/Magnum Photos

With 1969’s Easy Rider, which he co-wrote, directed and starred in (alongside Messrs Peter Fonda and Jack Nicholson), Mr Hopper personified the 1960s counter-culture as Billy, a shearling-clad, Zapata-moustached, cowboy-booted, bandanna-toting, finger-giving biker renegade who roars across the southwestern plains following a cocaine-smuggling deal, pausing only to ingest some LSD in a New Orleans cemetery. The $400,000 B-movie earned almost $60m at the time of its release, with The New York Times heralding it as “a travel poster for the new America,” and Mr Hopper himself describing it as “my state of the union message… a Western except the guys were riding motorcycles instead of horses”. Mr Hopper’s fondness for Western-inspired gear was no pose; he’d grown up in Kansas, where, according to Mr Peter Biskind in his account of Hollywood’s “sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll generation,” Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Mr Hopper had “developed a taste for beer at the tender age of 12, when he was out harvesting wheat on his grandfather’s farm”.

Get the look

WEAR YOUR ART ON YOUR SLEEVE

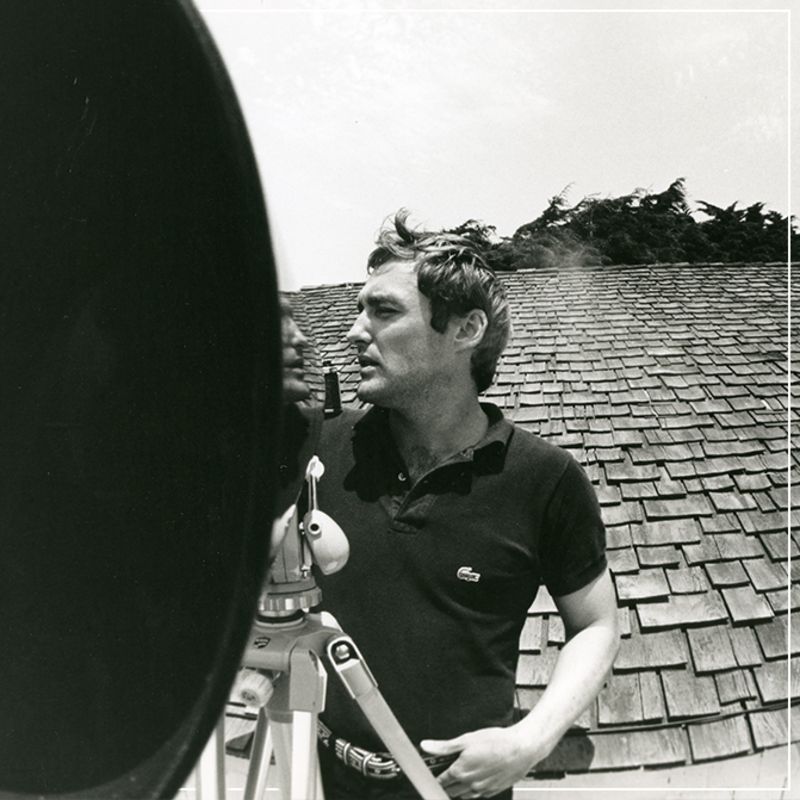

Los Angeles, 1960s. Photograph by Mr Robert Walker Jr courtesy of the Hopper Art Trust

As well as being a stellar – if often wayward – writer, actor and director, Mr Hopper was a dedicated art collector and a talented photographer. He began collecting pop art in the early 1960s, at the suggestion of Mr Vincent Price – yes, the horror movie mainstay – and bought a couple of early soup can paintings by Mr Warhol for $75. He would eventually amass a bunch of masterpieces by the likes of Messrs Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns and Jean-Michel Basquiat, all housed in a steel condo in LA’s Venice Beach that resembled a giant shipping container, albeit one designed by starchitect Mr Frank Gehry. His photographs – of the LA art scene, the civil rights struggle, Hells Angels at a diner pitstop – have been shown in museums and galleries worldwide. Here, Mr Hopper looks suitably saturnine (and makes an unimpeachable case for tucking your polo shirt into your jeans) in a self-portrait on an LA rooftop.

Get the look

RAISE HELL AND TURN IT UP

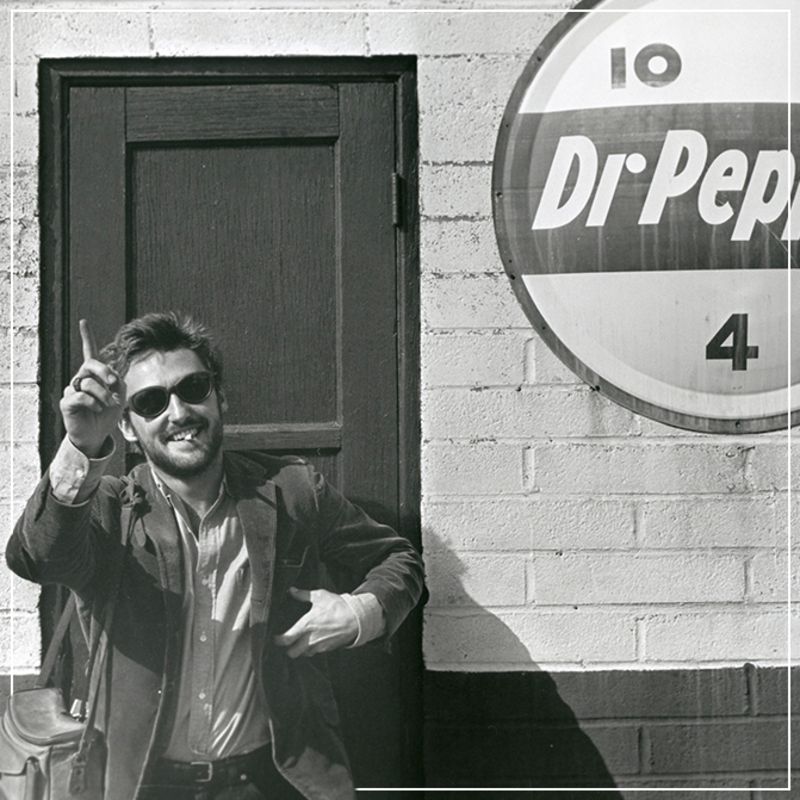

Los Angeles, 1965. Photograph by Mr Robert Walker Jr courtesy of the Hopper Art Trust

It’s ironic that Mr Hopper – here the epitome of dishevelled prep – should be pictured next to a sign for the carbonated drink that once boasted, in an ad slogan, that it was “free from caffeine and cocaine”, two things, along with alcohol, that Mr Hopper never fought shy of embracing. Looking back in the sober late 1980s, he described his former self as a “semi-psychotic maniac” who thought little of consuming half a gallon of rum, 28 beers, and three grams of nose candy – per day. Mr Hopper’s penchant for letting it all hang out – facilitated, as The New York Times put it, “by acid trips, a gun fetish, a tendency to overshare with journalists, and bouts of physical violence” – may have contributed to his very public meltdowns, but also enhanced his most indelible performances, from his burnt-out stuntman in 1971’s The Last Movie to the speed-freak photojournalist in 1979’s Apocalypse Now. As with many of Mr Hopper’s more outre characters, it’s hard to tell where life ends and art begins.

Get the look

GO CRAZY IN LOVE

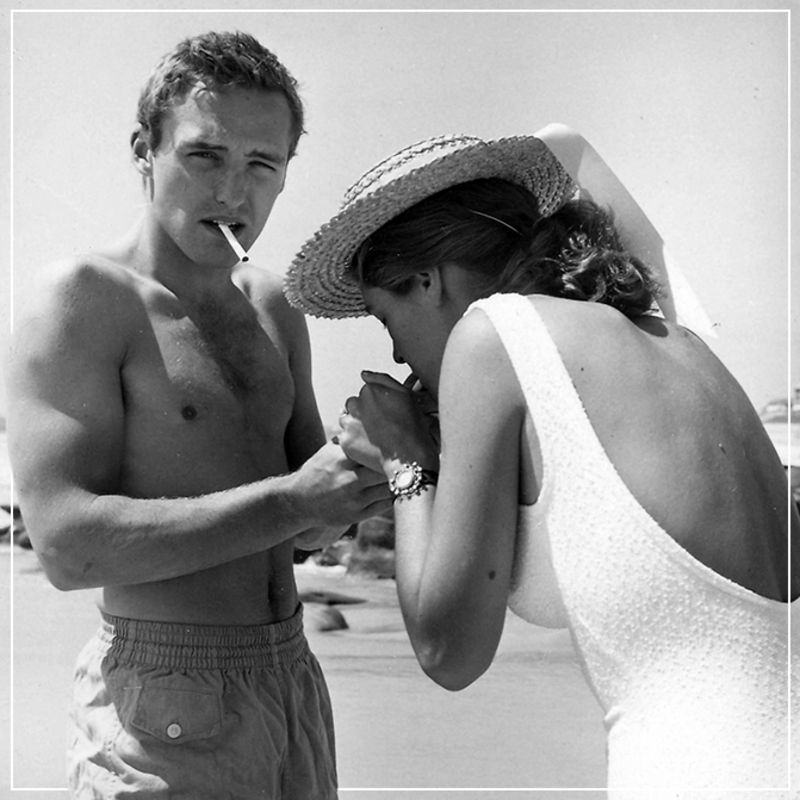

Mr Dennis Hopper and Ms Kim Tyler. Photograph by Globe Photos/ZUMApress.com

Mr Hopper had no problem getting ladies’ attention – as is plain to see above, he certainly was quite a sight in his swimming trunks – but he did struggle somewhat with keeping them on side. In fact, his personal life was as turbulent as his professional one; he was married four times and fathered five children. His first marriage, to Ms Brooke Hayward (whose mother, Ms Margaret Sullavan, had once been married to genuine Hollywood royalty in the shape of Mr Henry Fonda), broke down amid physical altercations and Mr Hopper’s penchant for falling asleep, drunk, while clutching a lit cigarette, thus repeatedly setting soft furnishings ablaze. He famously split with Ms Michelle Phillips, a singer in The Mamas & The Papas, after eight days of marriage: “Seven of those days were pretty good,” Mr Hopper once said. “The eighth day was the bad one.” Even in his twilight years, the flame still burned: so bitter were the divorce proceedings between Mr Hopper and his fifth wife, Ms Victoria Duffy, that he sought a restraining order against her, even though he was dying and virtually bedridden at the time. “Dennis had a tendency to fall in love with any girl who stood in front of him,” a friend of Mr Hopper’s elaborated to Mr Biskind.

Get the look

BE A REBEL WITH A CAUSE

Los Angeles, c. 1960. Photograph by Mr Robert Anzell/Everett Collection/Alamy

Mr Hopper and Mr James Dean were near-contemporaries; at 18, Mr Hopper found himself playing opposite Mr Dean in Rebel Without A Cause, and being heavily influenced both by his Method approach to acting (“we had a teacher-pupil relationship,” he said; “I had to learn to really drink the drink, not act drinking the drink”) and his reluctance to take direction (in an early Western, Mr Hopper deliberately mangled 87 takes of a single line after disagreeing with director Mr Henry Hathaway on how to play a scene). He also took some sartorial and presentational cues from his mentor, if this early publicity still is anything to go by. Witness here the Mr Dean-esque windbreaker, the Boulevard of Broken Dreams-esque soulful stare, and the nonconformist pop of the argyle socks. When he heard of Mr Dean’s premature death in a car crash, Mr Hopper said he “flipped out… I think I hit my agent… I really believe in destiny, and that didn’t fit in”.

Get the look

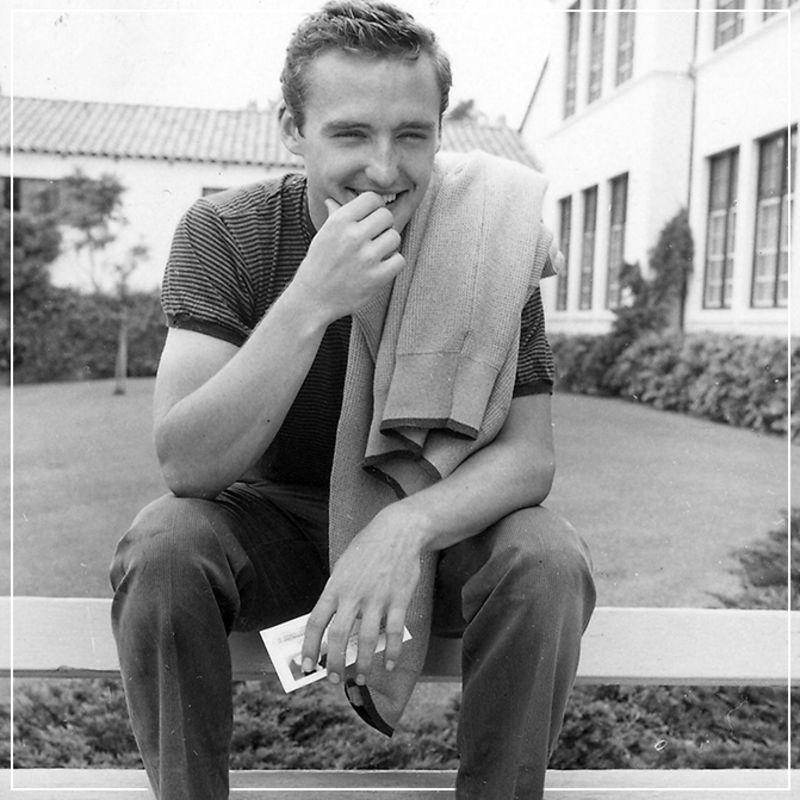

LET FASHION FOLLOW YOU

Photograph by Globe Photos/ZUMApress.com

When he was periodically blacklisted from studio lots, Mr Hopper would revert back to the art world, painting and sculpting as well as photographing and immersing himself in the exploding LA art scene of the mid-1960s, hanging out with future big names like Mr Ed Ruscha and Mr Robert Irwin, who were represented by the influential Ferus gallery, as well as appearing in some experimental films of Mr Andy Warhol’s, including The Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys. At such times, he would also revert to what his friend style writer Mr Glenn O’Brien called his “natty artist Angeleno look… bohemian, slightly strange, and surprisingly neat,” exemplified here by the striped tee, beat-up chinos, desert boots and – yes! – an artfully draped sweater. “Dennis Hopper didn’t follow fashion,” wrote Mr O’Brien, “it tended to follow him on his zigzag path through pop culture. But his look always had one very special quality. It was slightly unsettling.”

Get the look

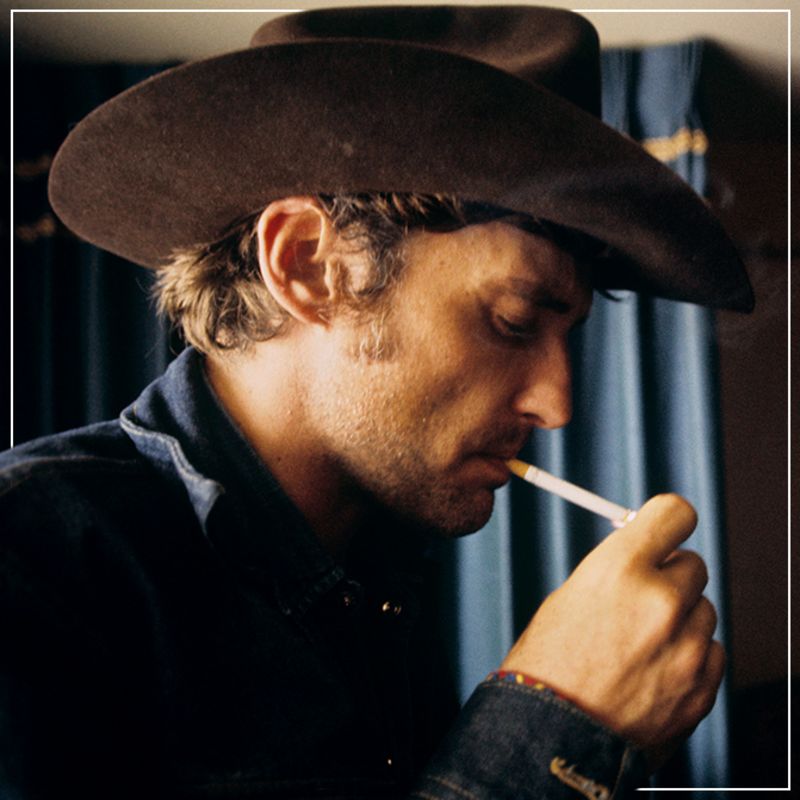

BE AT HOME ON THE RANGE

Los Angeles, c. 1969. Photograph by Mr Bruce McBroom/mptv.com

Mr F Scott Fitzgerald opined that there are no second acts in American life, but Mr Hopper didn’t appear to get the memo; after sobering up in the mid-1980s, he went on to play some of his most celebrated roles, including the mad bomber taunting Mr Keanu Reeves in Speed, and the gas mask-clad sexual psychopath Frank Booth in Mr David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (he telephoned Mr Lynch to demand the part, saying, alarmingly even for Mr Hopper, “I am Frank Booth”). As Frank, Mr Hopper wore Western-style shirts with silver collar points, and Mr Hopper was faithful to his patented bad-seed-son-of-the-cattle-baron look throughout his life, explaining that “all my Kansas uncles and grand-uncles, when they made it, they got a Stetson”. Mr Hopper became a regular patron of Nudie’s, North Hollywood’s renowned cowboy tailor, and once wore a white Stetson to the Academy Awards, prompting his erstwhile father-in-law, Mr Henry Fonda, to opine that he should be “spanked” for his effrontery.

Get the look

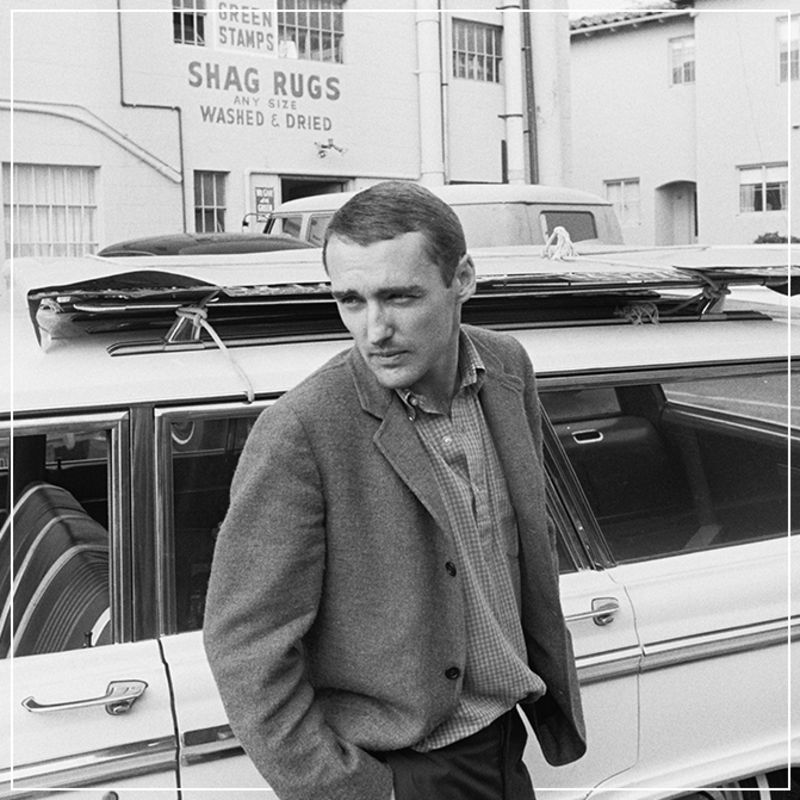

ALWAYS SNAP, CRACKLE, AND POP

“Snap, Crackle…”, self-portrait, Los Angeles, 1963. © Dennis Hopper, Courtesy of The Hopper Art Trust

It was Mr James Dean who suggested that Mr Hopper should start taking photographs, and “to look at the world through a frame”, advice Mr Hopper seized on with gusto. Between 1961 and 1967, he shot around 10,000 images, using high-speed black-and-white film for immediacy, shooting only in natural light and, as Mr Dean also counselled, choosing to “never crop, but use the still full frame”. Mr Hopper himself wrote that “I started at 18 taking pictures, I stopped at 31... I never made a cent from these photographs… but they kept me alive.” Mr Ed Ruscha calls Mr Hopper’s portfolio “a virtual dictionary of the city of Los Angeles”. Alongside capturing his friends and fellow luminaries (Mr Paul Newman, Ms Jane Fonda), Mr Hopper also turned his lens on himself, defining his image down the decades, “a strange blend of psychic volatility and explosive potential mixed with formal, polite, almost tranquil gentility,” as Mr Glenn O’Brien has it, and which can be seen in this self-portrait from 1963, in which a soft wool blazer and button-down overshirt fail to dampen Mr Hopper’s tumble-dried fervour.