THE JOURNAL

The Swedish interior architect embraces colour at work and in his London home .

We have out-grown ornament, we have struggled through to a state without ornament. Behold, the time is at hand, fulfilment awaits us. Soon the streets of the cities will glow like white walls!”

Thus thundered the modernist architect Mr Adolf Loos in his landmark 1913 essay “Ornament And Crime”. Today, 106 years later, one suspects that Mr Loos might have been rather disappointed had he found himself in 21st-century Parsons Green in west London. A genteel mixture of red-brick Victoriana, leafy public commons and Edwardian townhouses, this district feels a long way from the strictures of Loosian modernism. Glowing white walls, it certainly isn’t.

Fitting, then, that it should be here that an architect of a different stripe to Mr Loos has set up home. “I don’t ever want to feel plainness,” says the Swedish-born interior architect Mr Martin Brudnizki, sipping espresso at the breakfast bar perched in the centre of his kitchen. To his right, delicate botanical illustrations cover an entire wall, each clipped from a mouldering book of flora and fauna that Mr Brudnizki rescued from obscurity. Behind him, a set of large windows look out over London, the view shaded by a growing curtain wall of fresh green plants. “I’ve never believed in the minimal cube,” he explains calmly. “I believe in detailing the cube.”

Mr Brudnizki founded his eponymous London-based studio in 2000, extending operations to New York in 2012. Over the course of nearly two decades, Mr Brudnizki and his team have become renowned for their luxuriantly eclectic interiors – spaces that carefully cherry-pick elements from across la belle époque, Art Deco, Art Nouveau and mid-century modern. The studio has crafted interiors including the aquatic-inflected brasserie of fusion restaurant Sexy Fish; the drawing room-like space for the The Academicians’ Room at London’s Royal Academy; and, most recently, a pleasure-garden inspired refurbishment of Annabel’s private members’ club on Berkeley Square, to name but three.

In Mr Brudnizki’s work, materials, colours, patterns, architectural styles and textures mix freely, finding pleasure in an aesthetic of lavish melange. “I like mixing things up, because I find it much more interesting than when you try and make everything match,” says Mr Brudnizki. “We’ve had classicism, we’ve had modernism, we’ve had minimalism and maximalism. These styles are now all in the public domain, and what’s great about the present moment in design is that you can do whatever you want as long as you can conceptually back it up.”

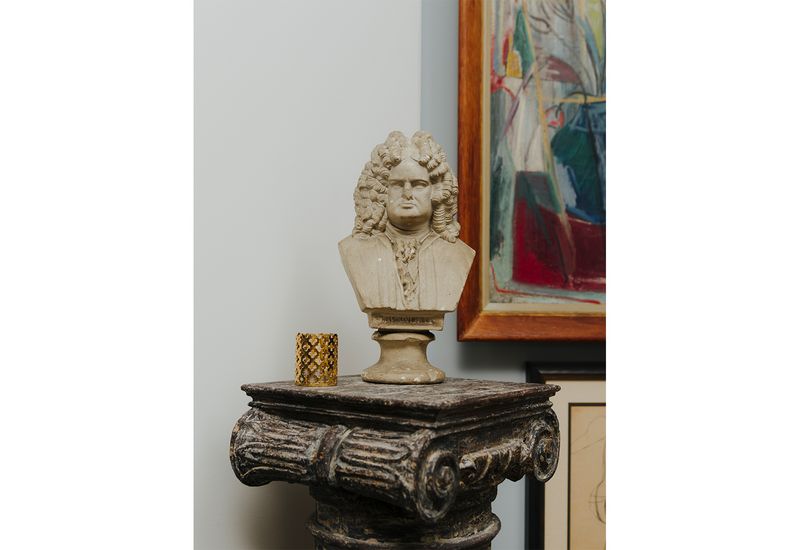

It is in this spirit of eclecticism that Mr Brudnizki has designed his own space, the top floor of a Victorian mansion block that he shares with his partner Mr Jonathan Brook. The pair have lived in the flat for nearly five years, having radically reorganised the space when they moved in. Today, the flat is designed so that not an inch is wasted, the rooms set up as pocket sanctums of sculpture, artworks, tchotchkes, books and textiles. It is a space in which a Bauhaus lamp inherited from Mr Brudnizki’s grandfather rubs shoulders with a classical bust of Mr George Frideric Handel; where a delicate wooden lady’s table is a happy companion to robust leather campaign chairs; and where shelves crammed with curios, books and photographs glow softly from the light of lamps nestled within.

What was the flat liked when you moved in?

A wreck. It hadn’t been touched in forever, although it was in a beautiful building. I like the fact that it’s Victorian and quite simple, because that ensured my approach to the interior design would have to be simple, too. What really drew me to it, however, is the view out of the kitchen over the city. The estate agent showed it to me before it went onto the market – he was hoping that someone with a vision would buy it and redo it to make the most of that view.

Did the idea of designing your own space appeal to you? Professional chefs, for instance, often say they can’t bear to cook at home

I know how I need something to work for me, but when it comes down to picking fabrics or colours, I almost go blank when doing it for myself – the remit becomes so broad. So, I thought about how I need to live, which is very important with real estate in London because it’s so expensive. All the space needs to work for its money, so we use every part of this two-bedroom flat every day. There’s not one single area that’s not used. When I moved in, I wanted to think about how to evolve my life and how I wanted to live now. So we created a separate dressing room because I wanted to separate the space’s functions, without making it unsellable in the future. That felt important because this is not the last flat I’ll have. This is not where it ends.

Typically when you think of Scandinavia’s design tradition, it’s a cool, studied minimalism that comes to mind. But your designs and this space are very sumptuous…

If you remove everything from one of my spaces – the colour, the patterns – you end up with a linear diagram that is actually quite simple. My approach – the lines that I draw – are quite minimal, but we always match that to dressing the space. We do that in a very architectural way, so the spaces still feel clear. People can go to Annabel’s, for instance, and understand that space immediately. There’s a lot to look at, but you can understand it.

Within contemporary architecture, there is often a certain snootiness towards ideas of dressing and ornament. Where do you think that comes from?

It’s the conflict between classicism and modernism that emerged in the 1920s. Art Deco, however, was a great moment – both classicists and modernists like it because it serves as an in-between area, and I think we’re now coming back to that kind of openness. In that sense, I really enjoy the hospitality work we do, because it’s about creating a world for people to enjoy themselves. You need to make it the best experience you can, because that’s what we do as a business – we craft experiences.

How do you achieve that?

I like layers. You have the architecture, which is simple and has colour, finish and texture, and then you can layer things like furniture, art and lighting. In our living room, for instance, there are four lights in the bookcase, so at night the room glows vey dimly. Then the bookcase is full of books, objects and photographs, because these are the layers that make a space a home and which make it interesting. A home is about me, and this is something I can do in design that is about me – it talks about what I like to read and watch, and my family and friends.

There’s a lot of mixing materials within your work – wood with marble, metal and lacquer, for instance

I like to create a mixture, and mixing materials is part of that. I could happily put a Bauhaus lamp next to a classical column, for instance, and then put a very modernist piece of sculpture on top of that. Layering is important for that because this space needs to be my refuge. When I come home, I still want to be stimulated. I can decompress here, but still feel I’m feeding my soul.

How does that design ethos carry across into the clothes you like to wear?

I would wear a striped shirt, and then a polka-dot tie, and then colourful Missoni socks. And I would mix two or three colours together – blue, burgundy, a little bit of green. The only time I wear black, for instance, is when I wear black tie. It’s such a sad and hard colour. Dressing is very important because it can set me in a certain mood. For some weird reason – and this is not done intentionally – when I dress to go to a presentation, I wear something that is connected to the scheme I’m presenting. I have always found that clothes are very important in my career and job, even before you’ve shown anything you’ve done. It sets a tone about your approach and detail. Your thought is how you dress.