THE JOURNAL

MP Massimo Piombo Neruda Grey Double-breasted Semi-lined Jacket Coming soon

It’s not easy being this good: the private battles of one of the Grand Slam’s brightest stars.

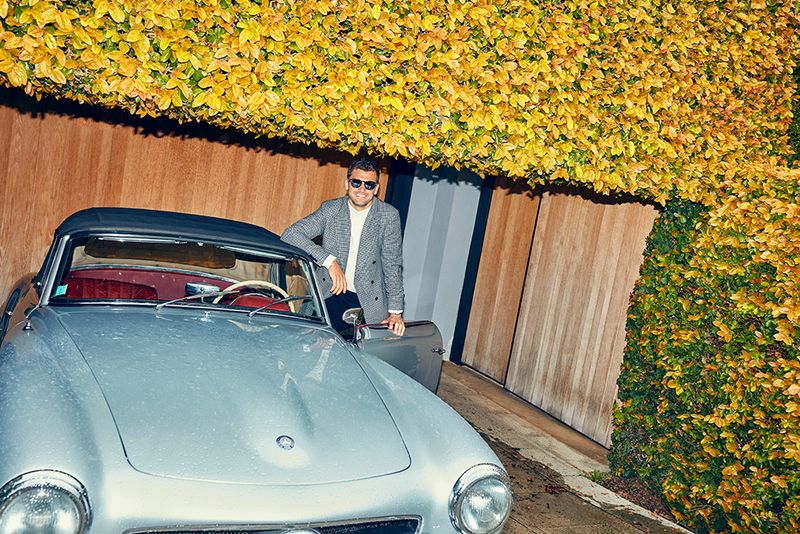

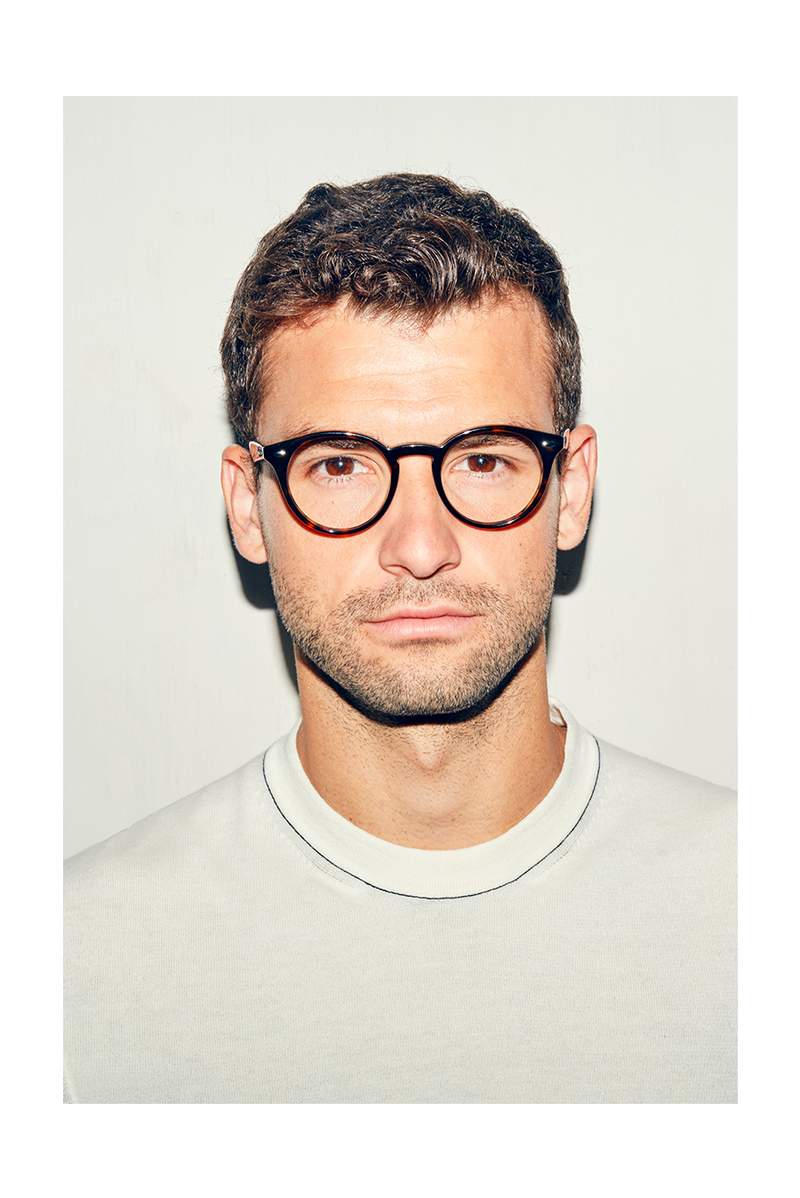

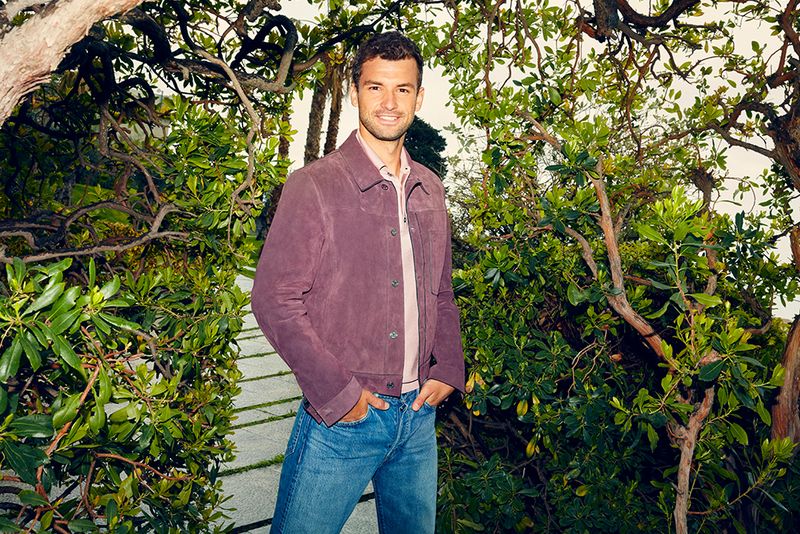

Mr Grigor Dimitrov strides through the foyer of the Royal Monceau hotel in Paris looking much like you’d expect a multi-millionaire professional tennis player to look. Tall with a purposeful gait and decked out in navy blue Nike, he has the permanent tan of someone who travels the world in pursuit of his first Grand Slam win. Yet one detail marks him apart.

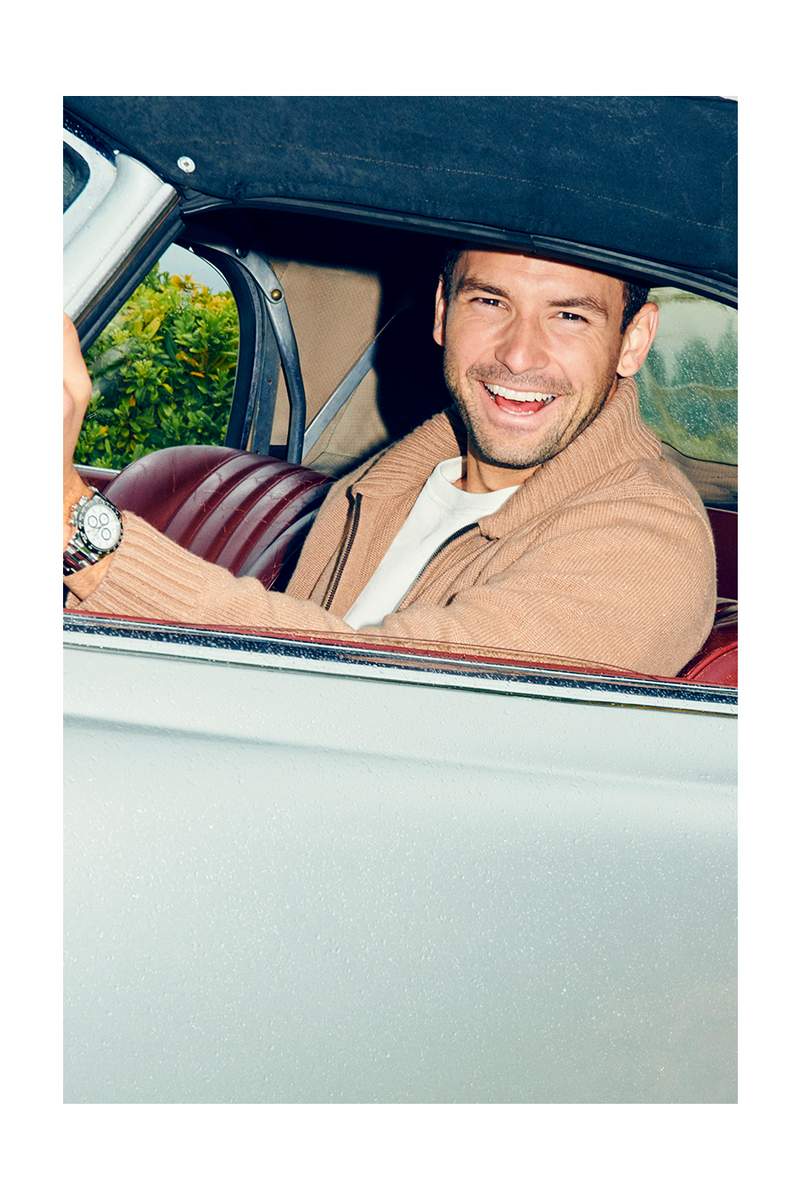

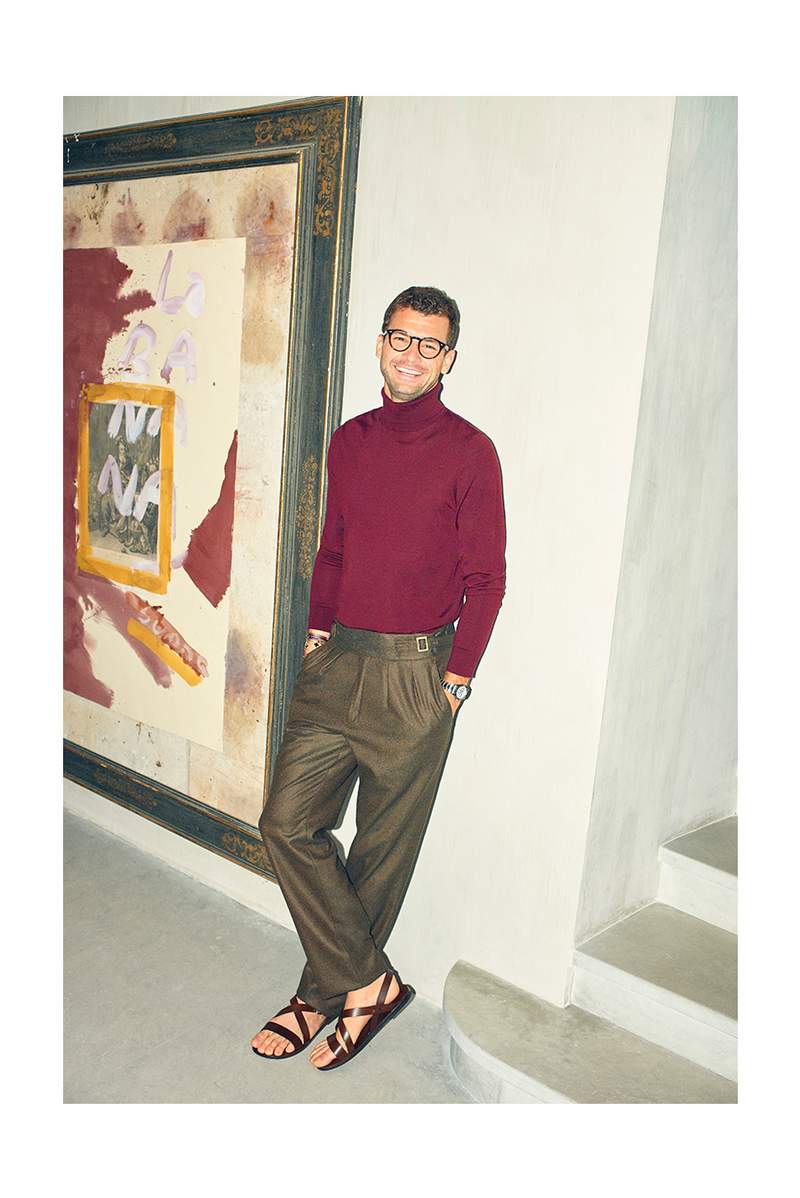

On his right wrist, Mr Dimitrov, the world number six, wears a small store’s worth of bracelets. These range from the luxe – Van Cleef & Arpels’ classic motif and a chunky, bent-nail-shaped Cartier Juste Un Clou – to homely, hippyish threads and a cross given to him by his mother. They are Mr Dimitrov’s signature. “A lot of people say, ‘Oh man, I love your bracelets,’” says the 27-year-old Bulgarian in his multinational accent, the consequence of going to live in Barcelona at the age of 12, then Paris and then Monte Carlo to pursue his dream. They also represent his ethos. “In order to be irreplaceable, you must be different, you know?”

Mr Dimitrov always wears his bracelets, even when he’s playing tennis (they’re covered with a sweatband). He is a wildly talented player, one of the few considered capable, eventually, of deposing Mr Roger Federer or Mr Rafael Nadal. His biggest win last winter, at the season-ending Nitto ATP Finals in London, confirmed that. On the court, everything seems perfect, uniform and elegant. Mr Dimitrov is a classically handsome player who has all the shots. Off the court, though, you get something surprising, mixed, someone who struggles to settle in one category. “I love Rick Owens,” says Mr Dimitrov, a dedicated follower of fashion. “Nobody would think that I love Rick Owens.”

We meet at the Royal Monceau on the eve of Roland-Garros, which tennis naïfs dub the French Open. Mr Dimitrov stays at the five-star hotel during the tournament, as do other members of sporting royalty. “There’s Olympia,” he says, as Ms Alexis Olympia Ohanian Jr, baby daughter of Ms Serena Williams, floats past in the arms of her grandmother. Mr Dimitrov is rumoured to have dated Ms Williams before moving on to a much longer relationship with her arch-rival, Ms Maria Sharapova. Now, though, he is dating the pop star Ms Nicole Scherzinger.

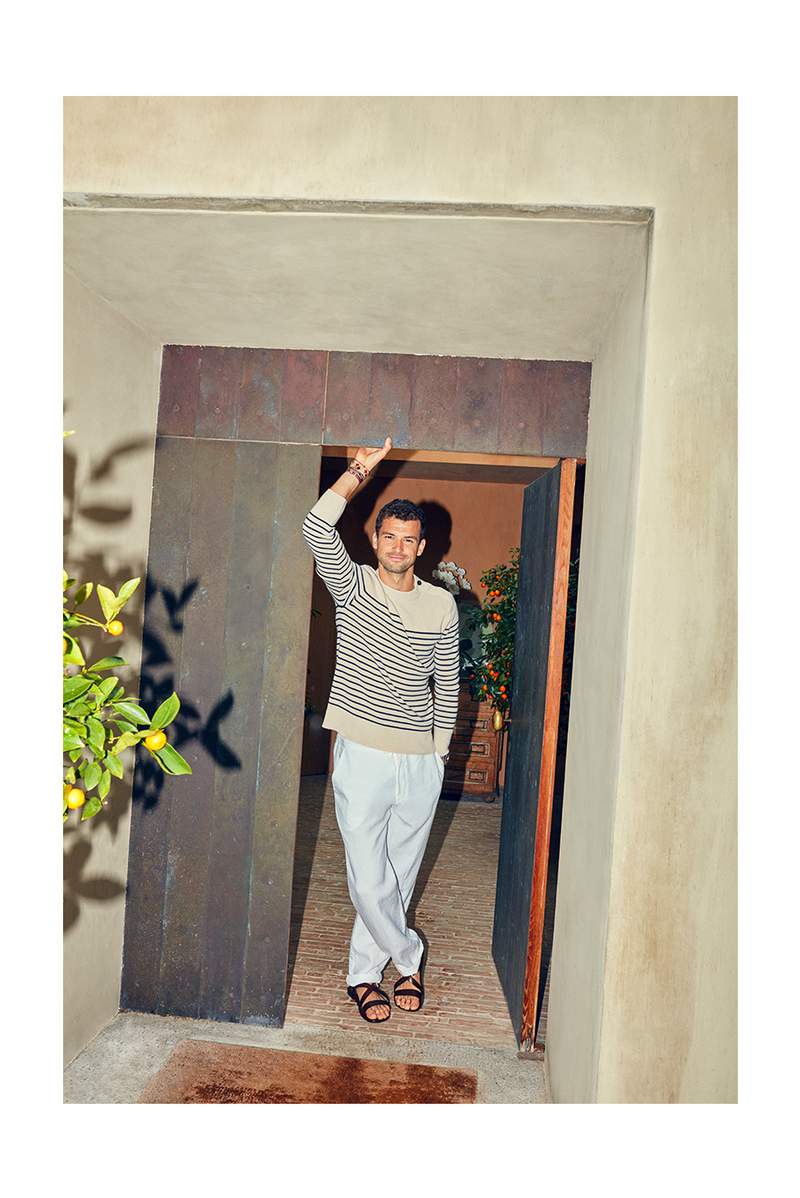

“It’s not easy,” he says. “The schedules are very heavy. But she’s doing a better job than I am of being able to come to most of the places I’m at.” The life of a tennis star is set to a relentless, fixed rhythm as they play across the globe from January until late November. They have four weeks off, then start all over again. “It’s insane,” says Mr Dimitrov, who spends the short off-season at home in Monte Carlo. “Then again, it’s our choice.”

Mr Dimitrov is chatty and relaxed, unassuming. “I’ve always been a very easy-going person,” he says. “I don’t want to say gullible, but when I saw someone, I always thought that person is the way they present themselves. But then with time and experience, I learned that’s not entirely true.”

Mr Dimitrov is having a solid 2018 after a fantastic 2017. It’s what was always expected of him, but it hasn’t been a smooth journey. After reaching the top 10 in 2014, after a stellar junior career, Mr Dimitrov suffered a vertiginous slump. In the summer of 2016, at the Rogers Cup in Toronto, things were at a low ebb. In the second round, he was a set down to the Japanese journeyman Mr Yūichi Sugita and was down 5-4 in the second-set tie-break.

“I’ll never forget that moment,” he says of a dizzying rally, which ended with Mr Sugita lobbing Mr Dimitrov at the net. “While the ball was flying, I was looking and I said to myself, ‘Don’t hit it between the legs. Just try to win the point.’” So he did. He ran back and hit a straightforward, simple – winning – lob. “And that point changed everything for me.”

The problem with having the luxury of choice is that you sometimes end up making the wrong one. Mr Dimitrov can hit pretty much any shot with ease. Indeed, he is well-known for trick shots, hit from between his legs or behind his back. They’re the moments we love to replay on YouTube, but they win you about 0.01 per cent of matches. Mr Dimitrov has finally accepted this, in no small part due to his coach, the Venezuelan Mr Dani Vallverdú, whom he first worked with that week in Toronto.

“In a way, it’s always been that,” he says. “It’s picking the right shot at the right time. And in order to do that, you need to be so clear in your head. It’s not as easy as everybody thinks.”

Brioni Cashmere Zip-through Sweater With Shawl Collar Coming soon

Mr Dimitrov’s downswing is easy to sum up. Having worked for so long to get to the top, the wheels finally came off. “I stopped with my coach,” he says. “I lost my ranking. I basically sucked at tennis. On a personal level, I was fighting with people and I went through my break-up [with Ms Sharapova]. And I was tired, simple as that. I was tired of everything, one by one, falling apart.”

Even when he was depressed at home, though, growing a “big beard” for months on end, Mr Dimitrov had an innate mental toughness that he could draw on, the product of growing up in the city of Haskovo in southern Bulgaria, the only child of Mr Dimitar and Ms Maria Dimitrov. His father, a fine tennis player himself, taught him the sport. He was tough but loving (“a real man”), and schooled his son in the whole game, not least the mental aspect.

“The majority of decisions, I’ve always taken by myself,” says Mr Dimitrov. “I even remember the first contract I ever signed. I was 13 or 14 years old. I got off the phone and my dad said, ‘What’s it going to be?’ He said, ‘It’s your choice. It’s your life.’ So you can understand that I like to take decisions on my own.”

Mr Dimitrov’s affability runs up against a stubborn single-mindedness. He refuses to say he has “sacrificed” anything for the game (“I don’t see it that way”) and he isn’t sentimental about leaving home at 12 in order to improve his game. “For me, it was not a problem,” he says. “I never, never missed it.” Part of this has to do with growing up in a “very tough neighbourhood” where “even just getting to school was a tough task”. Ask him where he would be now without tennis, and he says, “I’m getting the shivers, big time. I’m not sure I’d want to know.”

Once Roland-Garros is over (he lost to Mr Fernando Verdasco in the third round), Mr Dimitrov will head to Wimbledon, which holds fond memories for him. He won the junior title there in 2008 and reached the semi-finals in 2014. He will rent a house in the area with Mr Vallverdú and his parents will come and visit. He is looking forward to his mother’s home cooking. He will, as he has learned, keep things as simple as possible. He will also face his toughest opponent. “Sometimes, I have to beat myself first in order to beat the other guy,” he says. “And that sucks. I’m not gonna lie. But that’s me. And I don’t want to shy away from that.”