THE JOURNAL

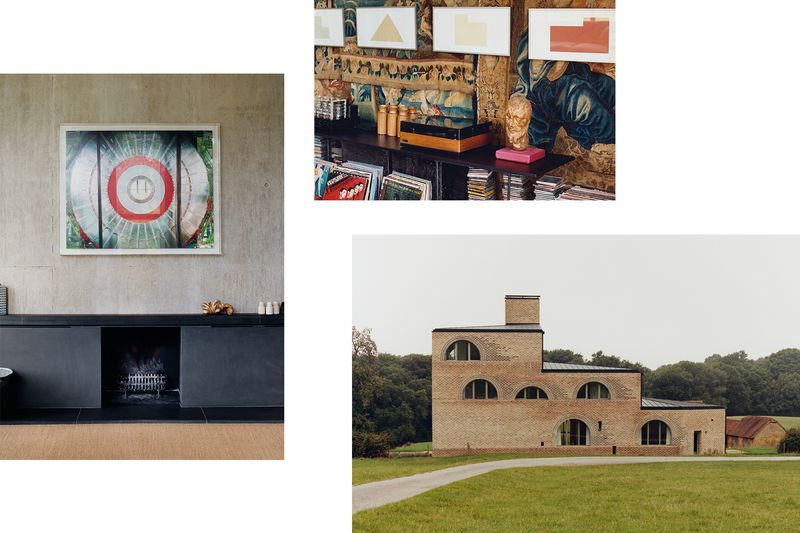

Architect Mr Adam Richards at home in Nithurst Farm, West Sussex, UK

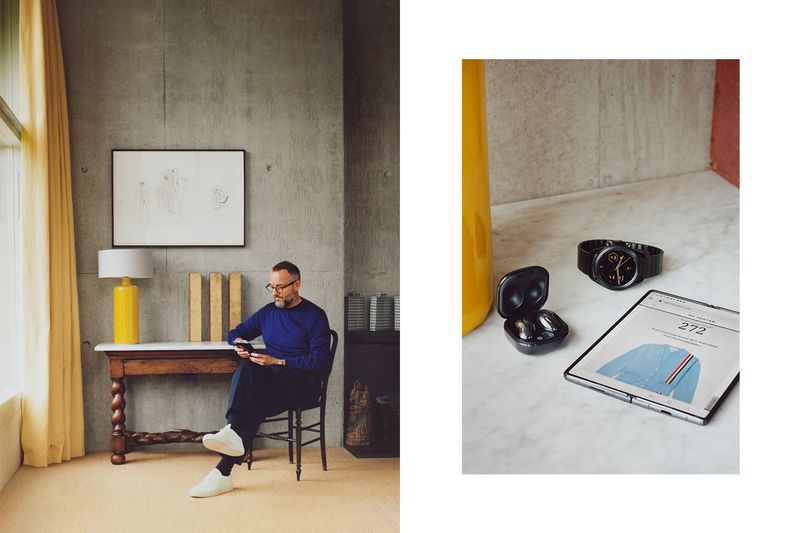

While millions of us have spent the past few months adjusting to the realities of working from home – brewing our own coffee, turning dining room tables into desks, and learning to live without the screen space of our dual desktop monitors – it’s safe to say that few, if any, have done so in quite as much style as the architect Mr Adam Richards. Not only is he armed with Samsung’s latest folding phone, the versatile Galaxy Z Fold2, but he’s got the “home” part of the WFH lifestyle nailed, too.

Nestled in a valley in the Sussex countryside and shrouded by ancient woodland, Nithurst Farm, the home he shares with his wife, Jessica, and their three children, isn’t visible from nearby roads. That’s for the best, too, because the sight of it would surely cause any passing traffic to slow to a crawl.

“I imagined it as a framework for the whole of our lives: somewhere you could host a fantastic dinner party, but also strip down a motorcycle”

Viewed from a distance, this spectacular three-tiered structure resembles the well-preserved ruins of a Roman villa, the brick arches framing its windows bringing to mind classical architecture. But move closer and its sharper edges come into focus, lending it the air of an old Victorian power station or engine room. As a home office, it’s certainly an arresting backdrop for Zoom meetings.

It’s something of an odd sight amid the green, rolling hills of rural England, but that’s not to suggest that it feels out of place, or as if it was just plonked there yesterday, as is the case with so much contemporary architecture. On the contrary, there’s a real permanence to this house, a sense that it has been there for centuries.

Mr Richards has every hope that it will live long into the future, too. “I wanted to design a building that would last 500 years,” he says. “We’re in a national park, a heavily protected landscape, and we’re surrounded by buildings that have been around for that long or longer, so I think it’s appropriate to think long-term.”

If the building’s brick exterior aims for something approaching timelessness, the interior, with its smooth concrete walls that nod to the work of Mr Tadao Ando, feels decidedly more modern. Indeed, if there is an overarching theme to this project, it is the coming together of seemingly disparate design influences to create a coherent whole, something best summed up by a wall display in the house’s main sitting room, in which a collection of 17th- and 18th-century tapestries forms a backdrop for a series of contemporary geometric prints.

The sitting room itself has a curious backstory, in that it was partly inspired by one of Mr Richards’ favourite films, 1979’s Stalker. In this Soviet-era art house classic from the iconic director Mr Andrei Tarkovsky, three men traverse a desolate landscape known as “The Zone” in order to reach “The Room”, a place where one’s deepest desires are supposedly granted.

The visual influence of this film is felt quite literally in the hallway dominating the centre of the house, which is modelled directly on the antechamber leading into The Room, the setting for the climactic scene in Mr Tarkovsky’s film. A striking space, its cavernous proportions suggest a church, while the concrete on the walls lends it the tough, post-industrial feel of an abandoned factory.

(As Mr Richards points out, Mr Tarkovsky was directing Stalker at a time when the ruins of 20th-century industrial spaces were just beginning to be appreciated for their beauty, in much the same way that Romantic poets had found beauty in ruined abbeys in the late 18th century.)

But what of “The Room” itself? As anyone who has watched Stalker will know, the men never actually enter; it is left largely for the viewer to decide what lies within. “It’s a mystery, but I saw it as a challenge or an invitation,” says the architect. “I didn’t feel that I had to emulate Tarkovsky’s room. All I really wanted to do was create the most beautiful room I could, a place where my own wishes could be met.”

The architect’s personal version of “The Room” is indeed beautiful, with views looking out over the nearby woods, but it’s also functional. This is an ethos that runs the entirety of Nithurst Farm. “I imagined it as a framework for the whole of our lives: somewhere you could host a fantastic dinner party, but also strip down a motorcycle,” he says of the main living space. “What I like in design are things that can have multiple uses, but also, crucially, multiple meanings.”

Indeed, the building now serves not only as a home for Mr Richards and his family but also as a place of work. This much was true even before Covid-19, when he was spending two days a week working from his office on the farm and the remaining three at his architecture practice in east London’s Shoreditch. The spread of the virus, and the subsequent lockdown, merely “consolidated something that was already happening”.

Nevertheless, the sudden change from working part-time in the office to working full-time from home has not been without its challenges. “We’re still on a learning curve and trying to fill the gaps in terms of what we are and are not able to do,” says the architect. “But it has been a fascinating experiment, and it’s made us all aware of just how much technology has made possible.”

Mr Richards’ experience of the past few months is hardly unique. While it’s always tempting to believe that we’re living through an era of exceptional progress, this is inarguably true of 2020, especially with regard to our changing working habits. The recent trend towards flexible and remote working has been turbocharged by the spread of Covid-19, with a McKinsey report published in April showing a massive surge in demand for the top video communication apps during lockdown.

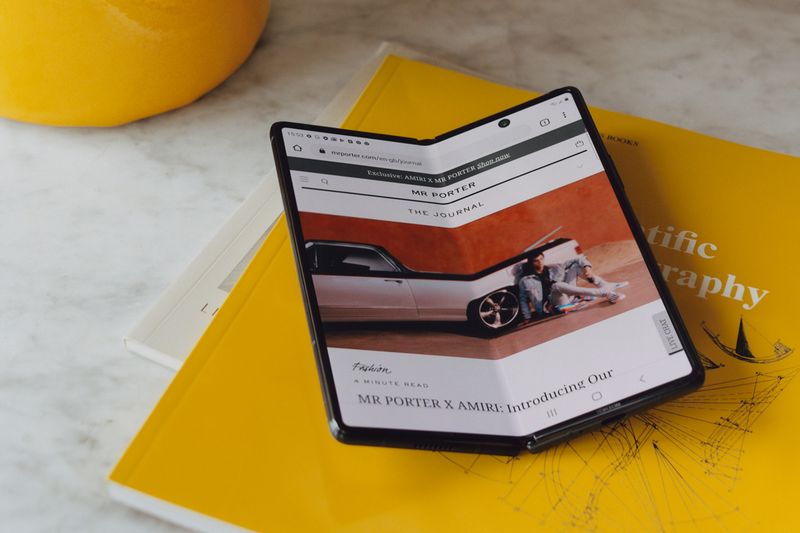

In this context, products such as the Galaxy Z Fold2, which offers the flexibility and productivity boost of a larger screen in a pocket-friendly smartphone package, seem increasingly compelling. Samsung’s new device follows on from the brand’s pioneering Galaxy Fold, which we profiled last year. If the original Fold was a bold leap into the unknown, the new Fold2 is an assured second step, further refining this radical form factor with a 6.2in front screen and improved multi-window functionality that makes it easier than ever to switch between apps. It’s a multi-tasker’s dream, in other words, and a serious life upgrade for remote workers who have found themselves spending more time working from their phones.

In the current climate, innovations like these are more than just desirable gadgets: they represent real progress. After all, if we are to finally break the chains that bind us to the office and the drudgery of the daily commute, we need tools that allow us to be just as effective at home – or, indeed, anywhere – as we would be at our desks.

Still, Mr Richards isn’t quite ready to abandon the office altogether. “I still miss certain things,” he says. “I especially miss sitting around the table with a big sketchbook and discussing ideas with my team.”

But does he expect certain working patterns to be retained once the pandemic is over? “My guess would be yes,” he says. From the rural idyll of Nithurst Farm, that doesn’t seem like such a bad thing at all.