THE JOURNAL

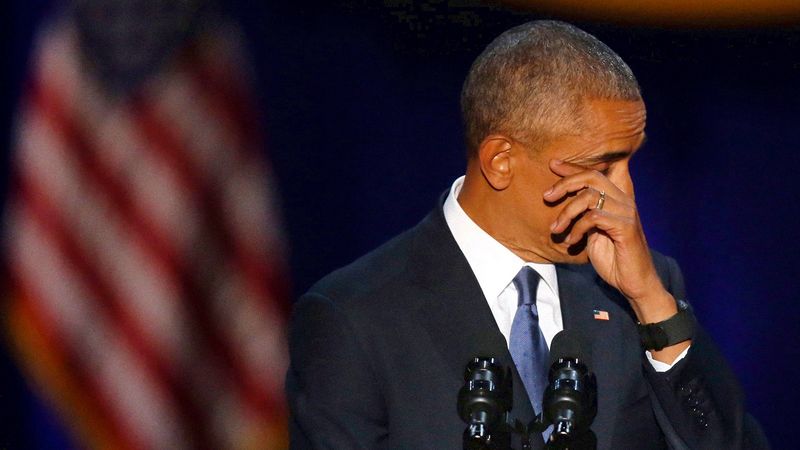

Mr Barack Obama wipes away tears as he gives his presidential farewell address at McCormick Place in Chicago, 10 January 2017. Photograph by Mr Charles Rex Arbogast/Shutterstock

It’s around 10.00am on a Tuesday in early 2021 and I am stood in my bathroom, staring back at myself in the mirror, trying not to cry. I’ve already been awake for five hours, I’m yet to have a shower and I’m supposed to be at work. And, very probably what has brought me this close to the edge, I’m also teaching phonics, the English language stripped back to its most basic compounds, to an uncooperative five-year-old boy: my son.

I’m not alone here. Well, I am – there’s no one else in the bathroom. (That’s a joke, by the way, to defuse tension. Which, as it turns out, might be part of the problem. But we’ll get to that.) In many respects, I am lucky to have a job – one that I love. And also a family during this trying time, even if, due to the sudden closure of his school, I am now forced to teach one of them, who also isn’t happy about the arrangement. There’s a multitude of reasons many of us have found ourselves in a similar place over the past year. But, these days, it’s not like it even takes this particular set of frustrations to bring me to tears. Bank adverts, Pixar movies, Marvel trailers – all of them now have me welling up. And that’s before we even get to Mr Keith Brymer Jones.

A self-styled punk-rock potter, Brymer Jones is one of the judges on The Great Pottery Throw Down, a show that has been running since 2015, but really struck a chord over its recent fourth run. Think of it as The Great British Bake Off with clay instead of cakes. However, if Brymer Jones is the Mr Paul Hollywood figure of Pottery Throw Down, what is really telling is that Hollywood’s trademark crushing handshakes are jettisoned in favour of a very different representation of masculinity.

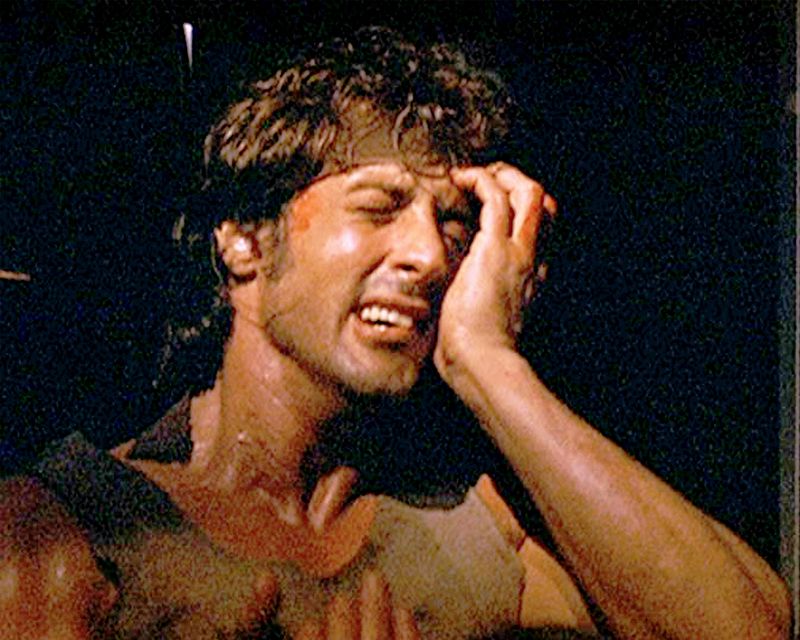

Mr Sylvester Stallone as Rambo in First Blood, 1982. Photograph by Paramount Pictures/CBS via Getty Images

“I get emotional,” Brymer Jones told The Guardian earlier this year, “because it’s a craft I love. It is my life. When I see a potter communicating their creativity via something they’ve made, I can’t help but cry. You’re watching imagination come to life. It’s so special.”

Brymer Jones’ tears might come from a very different place to those of us overwhelmed by the pandemic, but they have become emblematic of a modern depiction of men. Not that men haven’t cried before, or even haven’t been shown crying – from John Rambo in 1982’s First Blood to Mr James Van Der Beek’s much memed blub in Dawson’s Creek, popular culture is awash with tough (and not so tough) guys pouring their hearts out.

We’re also used to non-fictional men crying, notably in the sporting field (from Mr Paul Gascoigne to Mr Andre Agassi) and even off it (Mr Michael Jordan at his induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame). However, there is still a sense of artifice clouding this. Psychologists argue that this setting, sport itself, allows men to display emotion without anyone batting an eyelid, so to speak.

“No doubt the open conversations from sportsmen like Michael Phelps about his anxiety and addiction offers a high-profile role model for these conversations,” says Dr Zac Seidler, a clinical psychologist, men’s mental health expert and director of mental health training at Movember. “But the pressures are unique and many men excuse these guys’ emotions as they are in a totally different world. It’s also a hyper masculine space in many instances where crying alludes to effort or success.”

This analysis could also be extended to President Barack Obama, a politician noted for weeping on numerous occasions during his tenure in the highest of offices, or Mr Kanye West, when supporting his friend Mr Virgil Abloh following the latter’s first show for Louis Vuitton. Perhaps what is remarkable, then, about the men we’re now seeing on screen shedding a tear is not just that they are “real”, but that the stakes are considerably lower. Shows such as Queer Eye, The Repair Shop and The Great Pottery Throw Down seem to be packaged with this emotional charge factored in. And yet a man breaking down still feels like a spectacle.

“Men are more likely to suppress expression of their emotions... Or use humour to regulate them”

“There never was and never will be a time where a woman crying on TV is a sight to behold,” says Dr Seidler. “I look forward to having the same expectation for men. Guilt and shame are really prominent emotions for many men in public life and we are seeing these trigger crying on TV in our politicians and celebrities alike.”

To reduce this all to biology, humans have three basic types of tears: basal, to stop our eyes from drying out; reflex tears, which are a response to irritants (the old onions excuse); and psychic or emotional tears, which we’re dealing with here. The latter have a different chemical makeup to basal and reflex tears, containing more protein-based hormones. Mr Charles Darwin – a man, it should be noted – once dismissed them as “purposeless”, but science has come around since.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of crying is its function in eliciting an empathetic response from other humans, and this is certainly what these reality shows are plugged into. We are hardwired to feel sympathy for those displaying vulnerability. However, vulnerability is traditionally not something men have been good at dealing with.

A 2011 study affirms what most of us already suspect: men cry a lot less than women. Where women were noted to cry anywhere between 30 and 64 times a year, for men, the frequency is more like five to 17 times. There are biological reasons behind this – testosterone is known to inhibit crying, while prolactin, a hormone generally seen in higher levels in women, may promote it – but that’s not the whole story.

“This is a consistent finding even in cross-cultural studies across many different countries,” Dr Lauren Bylsma, assistant professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Pittsburgh, notes of the 2011 report. She is something of an expert in crying (in that she studies it rather than she’s really good at it). “We don’t know the exact reason, but it is likely a combination of biological, psychological and socio-cultural. Women tend to be more emotionally expressive in comparison to men and are more likely to suffer from problems with depression and anxiety.”

Messrs Kanye West and Virgil Abloh embrace on the runway at the end of the Louis Vuitton SS19 show, Paris, 21 June 2018. Photograph by Mr Laurent Vu/Shutterstock

“There is plenty of evidence to show that young boys actually have a wider emotional spectrum than girls,” says Dr Seidler. “When masculine socialisation starts to creep in around the age of five, you see a distinct shift in their emotional expression as sadness, vulnerability, fear. Thus, crying becomes aligned with femininity and a weakness in their eyes. The world starts to respond to boys in different ways, respecting stoicism and expecting emotional restriction. The vast majority of boys strive to live up to this, to their own detriment.” In short, this is not just a thing that I have to face in myself, but also one that my son is only just beginning to encounter, and that we need to tackle together – after phonics, obviously.

“The stigma of seeking emotional support, such as going to therapy, has been reducing for both men and women,” says Dr Bylsma. We’re all going through this. “But [it’s] perhaps a bigger change for men.”

And that’s the crux: men have so much more ground to cover, which is why this shift seems so much more pronounced. “Men are more likely to suppress expression of their emotions – particularly vulnerable ones, such as sadness or fear – perhaps due to social or cultural factors,” says Dr Bylsma. “Or use humour to regulate their emotions.” (I’m certainly guilty of that.)

“It’s evolutionarily useful to tell yourself and others that you need an open ear or support, it saves lives”

The catharsis reached through crying is “essential”, says Dr Seidler. “We all know that feeling when we just need to let it out. Crying doesn’t have ramifications on others like punching a hole in a wall or drinking excessively to release the pressure,” Dr Seidler adds. “It’s evolutionarily useful to tell yourself and others that you need an open ear or support, it saves lives.”

It is perhaps ironic, given that women are more prone to crying, that there is evidence to suggest that men are likely to get more out of crying. Or, at least, it doesn’t make them feel as bad. “Men [tend] to feel less physically depleted after crying compared to women,” Dr Bylsma says. Although, in truth, she adds that there is a lot more research to be done. “Many studies only focus on crying in women and don’t compare to men, so this is a limitation of some studies.” (A nod to Ms Caroline Criado Perez’s_ Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias In A World Designed For Men_ here – this is one area where we know more about women.)

How does Dr Bylsma suggest approaching another man who is clearly upset? “Listening and showing empathy, understanding and support and not trying to invalidate the crier’s emotions would be critical. Using humour or distraction could be seen as invalidating unless the person was specifically seeking a distraction away from their emotional distress.”

And this is no less true when confronting our own feelings. To return to where we started, me in the bathroom, making a joke of trying not to cry, perhaps the question shouldn’t have been “What drove me so close to tears?” Rather: “Why did I hold back?”