THE JOURNAL

He’s survived trips to both poles and a firing squad – explorer and Panerai ambassador Mr Mike Horn on derring-do and near-death experiences.

Where is Mike now?

So wonders the website of Mr Mike Horn. On previous form, the explorer could, frankly, be anywhere. Touching the clouds on an 8,000-metre peak. Swimming with sharks off Cape Town. Traversing South America (on foot), trekking the North Pole (in darkness), following the equator around the globe (solo, save for the occasional death squad).

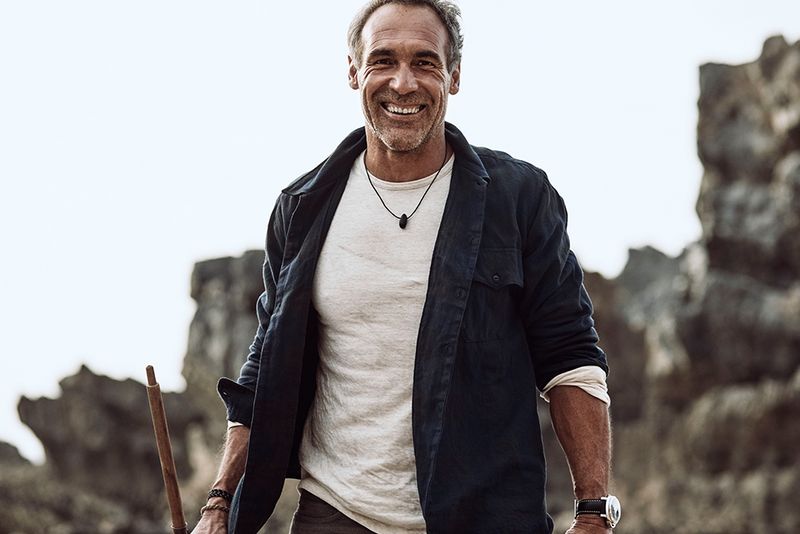

But right now, the 51-year-old is bounding up Adraga beach in Portugal, at dusk, shoeless and topless. Sturdy and broad-shouldered with a shock of silver hair, a smile to light up a polar winter and a handshake so firm, even being greeted by the effervescent Mr Horn is an adventure.

We are near the town of Sintra, on Portugal’s Atlantic coast. Mr Horn has spent the day being photographed, buffeted by autumn winds gusting from the ocean, all in the interests of assisting the long-standing sponsors of his daredevil adventures, the venerable Italian watch company Panerai, which has a long history of supporting yachtsmen and explorers. (It is also newly available on MR PORTER this week.)

Some middle-aged men would find that gruelling. Those middle-aged men haven’t sacrificed their fingertips to frostbite and count the amputations as “one of the perks of the job”. But most men aren’t Mr Horn, a father of two grown-up daughters who lost his wife to breast cancer, but was sincere in his offer that he die with her before she passed away. In fact, no man is Mr Horn, probably the world’s greatest living explorer.

The South African adventurer grew up roaming the wilderness beyond his Johannesburg backyard. As a teenager in the army, he had his first experience of the limits of human endurance. He nominates his father, a rugby-playing academic, as the hero who spurred him on to ever-greater heights. As the elder Mr Horn would tell his son: “If your dreams don’t scare you, they’re not big enough.”

His father, who died when Mr Horn was 18, wouldn’t be disappointed. This man with a degree in human movement science is currently in the middle of a two-year circumnavigation of the globe via both poles. He’s 17 months into the 24,000-mile odyssey. Is he on schedule?

“Ja, ja,” he shoots back in his thick accent, “simply because I crossed the Antarctic much quicker than I ever expected.”

For that leg of this epic undertaking he’s titled Pole2Pole, Mr Horn packed food for 120 days. Working from his base in the Swiss town of Les Moulins, he derived his calculations from previous expeditions undertaken by Norwegians Messrs Børge Ousland and Rune Gjeldnes. He figured he might do the 5,100 km in around 110 days, give or take. As it turned out, he completed the journey in 57 days.

“Fifty-six days and 22 hours!” he clarifies with a grin. He completed the leg in pretty much half the anticipated period. How exactly?

“I changed my biological clock,” Mr Horn replies matter-of-factly, as if talking about changing his socks. “Instead of having a 24-hour day like a watch would give you, I would have a 30-hour day.”

He could do that because at the southern pole he was operating in 24-hour sunshine, “and it never becomes dark”. Under “normal” conditions – that is, the kind of 24-hour day us mortals know – Mr Horn would sleep five hours, eat five hours and walk for 14 hours.

“But in a 30-hour day I sleep for five, eat for five – but I walk for 20. So every fourth day I gain a day. By doing that, by changing my biological clock and just spending more time out there, all of a sudden 57 days becomes a reality.”

Mr Horn is here on terra hospitable, 45 minutes outside Lisbon, taking a short furlough from his Pole2Pole exertions to update his sponsors on his global peregrinations. Key among those is Officine Panerai. Of all the watch companies with whom the dauntless outdoorsman could have partnered, why them?

“Because they believed in me from the start,” he states. The partnership began in 2001, when Mr Horn won the Laureus World Alternative Sportsperson of the Year Award. Afterwards, his compatriot Mr Johann Rupert, the chief executive officer of luxury goods company Richemont, owners of Panerai since 1997, approached the victor, unstrapped his own watch and handed it over. “From now on, you will only wear Panerai,” the CEO declared.

It was a marriage made in the extremes of the planet. For each expedition Mr Horn subsequently undertook, Panerai has made a bespoke watch, responding to his supplied specifications.

“For example,” he begins, “the temperatures that I will encounter. On an expedition like Pole2Pole, I was at -70ºC in Antarctica, and then I’m crossing the equator at temperatures of up to 40ºC.” Hence the new Panerai PAM 307, “a serious bit of kit” built to withstand excesses of temperature, and of pressure – by the way, this mountaineer is also a deep-sea diver.

“They have to make a watch where the oils don’t freeze,” he continues. “Liquid crystal freezes and in that scenario it’s very difficult to use any GPS – you have to heat up the liquid crystal screens before you can find out your location. You must be able to rely on your equipment. Because for me, obviously, the time is direction. The time is the position of the sun. The time is where I determine my north and my south and my east and my west.”

Panerai’s heritage offered foundational peace of mind. Established in Florence in 1860, its timepieces were initially targeted at sailors, specifically the Italian navy. These were precision instruments, beautifully crafted for sure, but prized for their reliability. As Mr Horn puts it in the elegant-but-forceful phraseology that has helped him develop a parallel career as a motivational speaker: “What I do, it’s not about money, it’s about life. Footballers or tennis players or a golfer – they would lose a match. We lose a life. And a life we don’t count in dollars. We count it in human relationships.”

Thus far, Mr Horn has been fortunate. Frostbite during his 2002-2004 Arktos trip around the Arctic Circle led to his thumbs being “rearranged and the bones cut out with laser,” he says blithely. It could have been a lot worse. “In our sport, if you can call it a sport, you’re lucky when you become old. Usually to lose a fingertip or two gives you the opportunity to still go out there and try again.”

Indeed, that highly-engineered steel has literally saved his life. “When I was climbing on Broad Peak [on the Pakistan/China border] in 2010, I used one of my Panerai watches as an anchor point. I wedged it into a crack in the rock, then put my rope round it, then abseiled down. I had no other choice – I was out of pitons [spikes] completely – and this watch was the thing I trusted the most [because] of the quality of steel they use. By using the watch in that way, I was able to get off the mountain. Otherwise I’d be stuck above 8,000 metres. And I’d been up there too long at altitude without oxygen. So it was this or die,” he says simply. “But I had to leave the watch there.”

Mr Horn cites another brush with mortality in his 20 years of epic explorations: an incident in Africa in 1999, during his Latitude Zero encircling of the globe.

“I was put in front of a death squad in the Democratic Republic of Congo. They shot the other guy that was caught with me. He was someone I’d met along the way – and maybe he really was a spy. I wasn’t, but we were associated.”

It’s a narrow escape he still doesn’t take for granted. Mr Horn considers himself having had a full life – full almost in the sense of being complete.

Indeed, when his wife was ill with the breast cancer that would eventually kill her in February 2015, “there was a moment when I said to Cathy: ‘I would want to die with you. The kids are old enough and on their way. I’ve done what I would have done.’”

In fact, her devoted husband continued, “if I could I would exchange my life with your life. I would die for you.” Mr Horn shrugs. “Because the moment that I survived that death squad was the moment that the rest of my life was a bonus. And it’s been ongoing for 17 bonus years.

“So when my wife got ill, I said, ‘F**k, this is not fair. I must die.’ And she said: ‘Mike, you mustn’t die. You’re made to live. Now you live for me. Just live for both of us.’”

As he readies for the next leg of Pole2Pole – up through the Himalayas and an attempt at Zemu Peak, which he describes as the last unclimbed mountain on Earth – that’s clearly a mantra Mr Horn will live until he can climb, dive, ski, sled or trek no more. Soon, he’ll be deep in expedition mode once more, consuming up to 12,000 calories a day, “the equivalent of what one person would eat in six or seven days. It begins with a lot of olive oil, macadamia nuts, fatty food to fight the cold. To have fuel in my tank to pull that sled. I’m a big meat eater! Chicken is like a salad for me!”

Still, he’s not entirely superhuman. He cheerfully concedes that he has a “rubber arm – even if I don’t feel like having a drink, it can be twisted!” What, then, did he do to celebrate his 50th birthday last July? Book a couple of DJs and sort out some dancing and boozing?

“Oh, if I was in a place where I could have a DJ, dancing and boozing, I’d do it! But it was nowhere close to that, so I had to make it exciting. So, I wanted to touch a rhino on the backside. I was stalking a rhino alone for about eight hours in Namibia!”

Then it was back home to sit on the couch in his sweats for a Game Of Thrones binge?

“I’ve never done that, ha ha! No, never! I don’t do Netflix and chill. But, hey, if they sponsor me,” globe-trotting, risk-taking, rhino-rubbing Mr Mike Horn hoots, “why not?”