THE JOURNAL

Watching two professional ballet dancers rehearse, up close, feels like spying on something steamy. Breasts are heaving, muscles are bulging and, if you listen closely, you can hear breaths quicken as the action speeds up. Most romantic entanglements, however, are not rehearsed over and over for weeks, and do not typically take place in large, well-lit rooms, while five or six people look on and a pianist scores the movements. But, at London’s Royal Ballet, they allow 20 to 30 people to watch, wearing headsets, peeking into the studio through a long horizontal window designed for such voyeurism, while Mr William Bracewell and Ms Fumi Kaneko work out the kinks of Twinkle, a new short ballet.

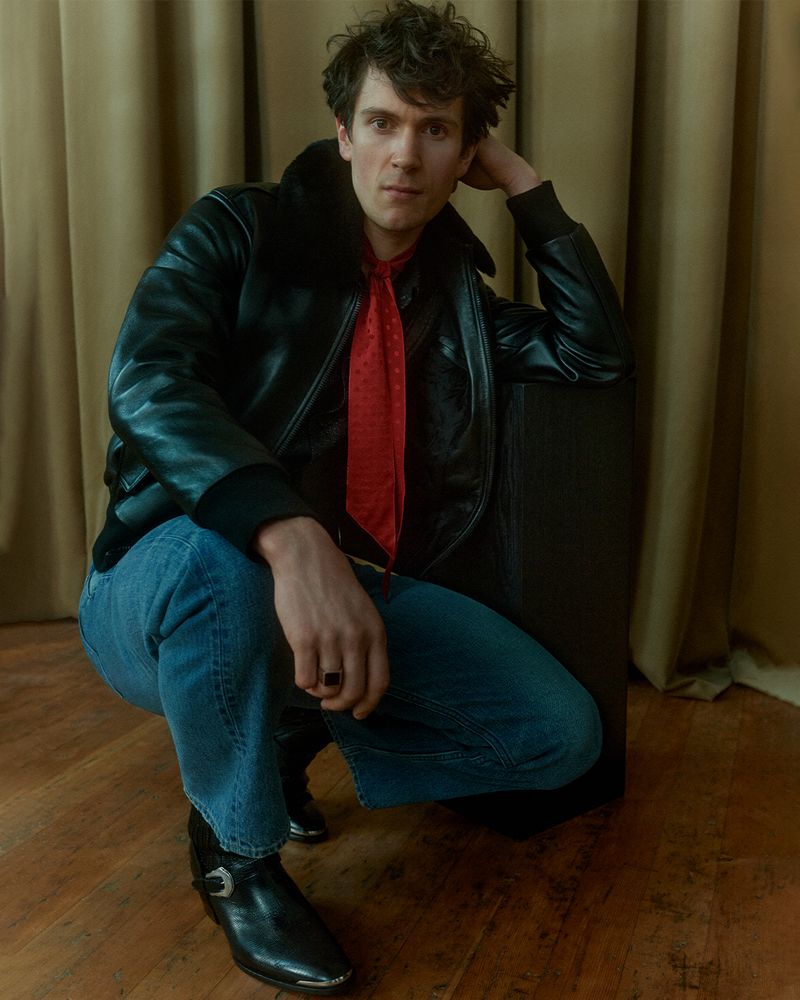

Bracewell, a principal dancer with The Royal Ballet, and the first person of Welsh descent to achieve such a title, is also an actor, an artist and a sportsman. He’s all of these things at once while dancing ballet. This is evident in the effortless way in which he hoists Kaneko into the air, over and over again, while collaborating with the choreographer Ms Jessica Lang on this new piece. The apparent ease with which the dancers move (he: lifting and leaping; she: balancing on toes) belies the gruelling physical work that got them to this very moment.

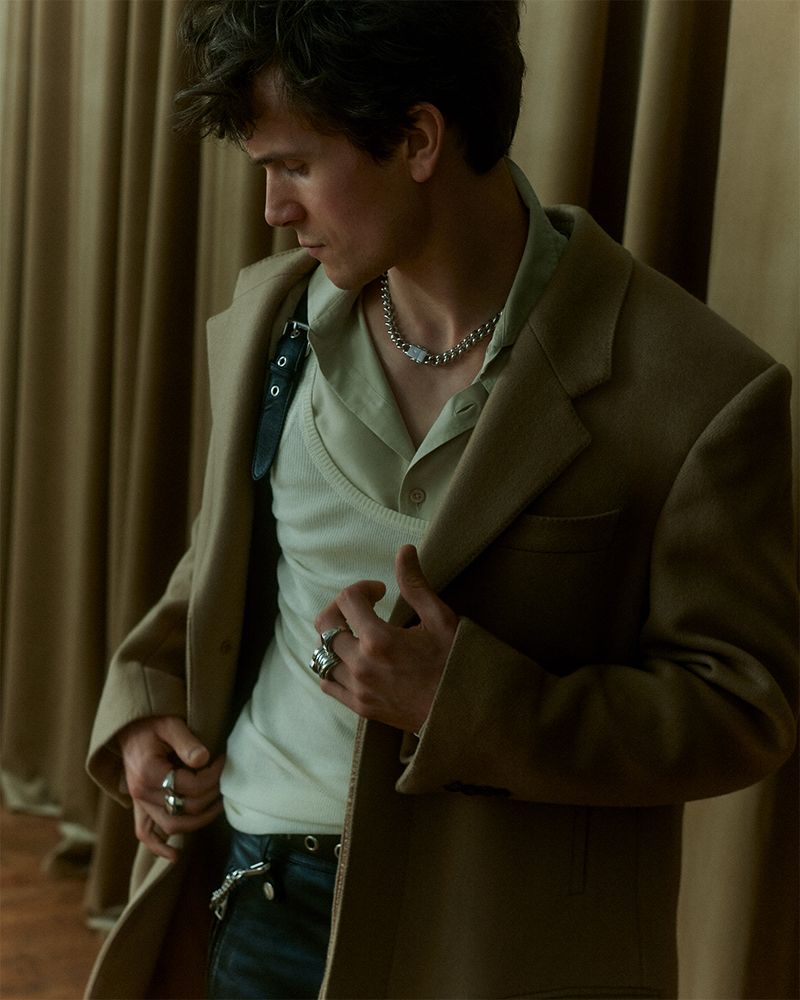

Bracewell is soft-spoken with enviably wavy hair and biceps cut from marble. He weaves through the labyrinthine studios and back rooms of the Royal Opera House carrying a workout bag with a protruding, torturous-looking spiked foam roller. His workdays begin at around 9.30am and include a mix of ballet classes, run-of-the-mill exercise (weight training, Pilates) and rehearsals. On rehearsal days, they end at 6.30pm, on performance days, after 9.30pm. Almost every moment of almost every day – they have class every day except Sunday – is spent in motion. It’s a physical schedule that explains why ballet dancers are so incredibly fit – and why their careers don’t often extend past the age of 40.

Bracewell is 32. “There is a limit, there is a timeframe,” he says. “In terms of high-impact principal roles for men, if you’re 40, 45, you’re doing really well.” Dancers must face their retirement much earlier than most working adults, and plan what’s coming next. It’s something he was forced to contemplate earlier than anticipated after a back injury left him bedbound a few years ago. “That was a really interesting but challenging and scary physical and mental experience,” he says now.

He went from constant activity to being unable to move for six weeks. “My brain has really blanked out big portions of that time. I remember snippets of my mum and my boyfriend being there.” After one day of prescription painkillers, he switched to ibuprofen. “I remember trying to explain to my mum that I wanted to watch the X-Men films, but it took me 15 minutes to get it out. I hated it.”

After this period of bed rest, Bracewell was back in the gym with the physio team at the Royal Ballet, working hard to regain what he had lost. He was also, quietly, exploring his options for a life beyond dancing. “I started to shadow some of the artistic team and understand how this building works,” he says. “I would have been telling myself I was just keeping busy, but there was an element of, ‘If I don’t make it back, I need to…’” He trails off, wincing at what might have been.

Injury is inevitable in the world of professional ballet: so much so that the big companies will have departments dedicated to supporting injured dancers, much like professional sports teams. “It is valued here, the rehab process,” Bracewell says. “It’s part of the job.”

Because he’s a principal dancer – the highest rank within a dance company – Bracewell only performs the big shows once or twice. His latest turn as De Grieux in Manon was a two-time affair, and he will perform in the upcoming four-month run of Swan Lake only five times. The dancers in the corps (the supporting dancers who do not play the starring roles) will dance in almost every performance.

“I think it’s so much harder [to be a corps dancer],” Bracewell says. “Maybe it wouldn’t have been enough [to keep me in this career].” Being a soloist and a principal means being able to take on some of the most renowned roles in the industry – Mr Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, for example, has been running since the late 1800s. Most dancers never become soloists or principals.

“I don’t know if you’d be able to put the amount of work in if you didn’t love it,” Bracewell says. And he loves it. He even found some unusual joy during his injury rehab: “Pushing so hard on a bike to get my cardiovascular strength back that I, like, vomit… I mean, I kind of loved that part of it.”

He talks about learning a new part like any Hollywood actor, only it’s more interesting to listen to (no blah-blah-blah about “craft”). “Sometimes, things come along and you’ve seen them done for years by the greatest dancers, and you start rehearsing, and you think this is terrible and I’m terrible.” Dancers rehearse in studios lined with mirrors, so they’re constantly watching themselves make mistakes or make beauty. It’s like being in a mirrored fishbowl.

While they are rehearsing Twinkle, he and Kaneko are observing their own movements, Lang and her husband and collaborator Mr Kanji Segawa are taking mental notes and Lang’s assistant records the whole thing on an iPad. Tiny adjustments – “look to the side instead of forward” – change everything and their muscle memory is astounding.

After a run, Lang will say, “Yes, that’s perfect, do what you just did,” and Bracewell and Kaneko will simply do it again. Bracewell lifts Kaneko above his head so many times, he would be forgiven for doing that thing the rest of us do when working out: stopping and shaking out his arms while ruefully mouthing “I’m so out of shape” to the instructor. But they don’t stop and rest, and they don’t look tired, and they don’t look sweaty.

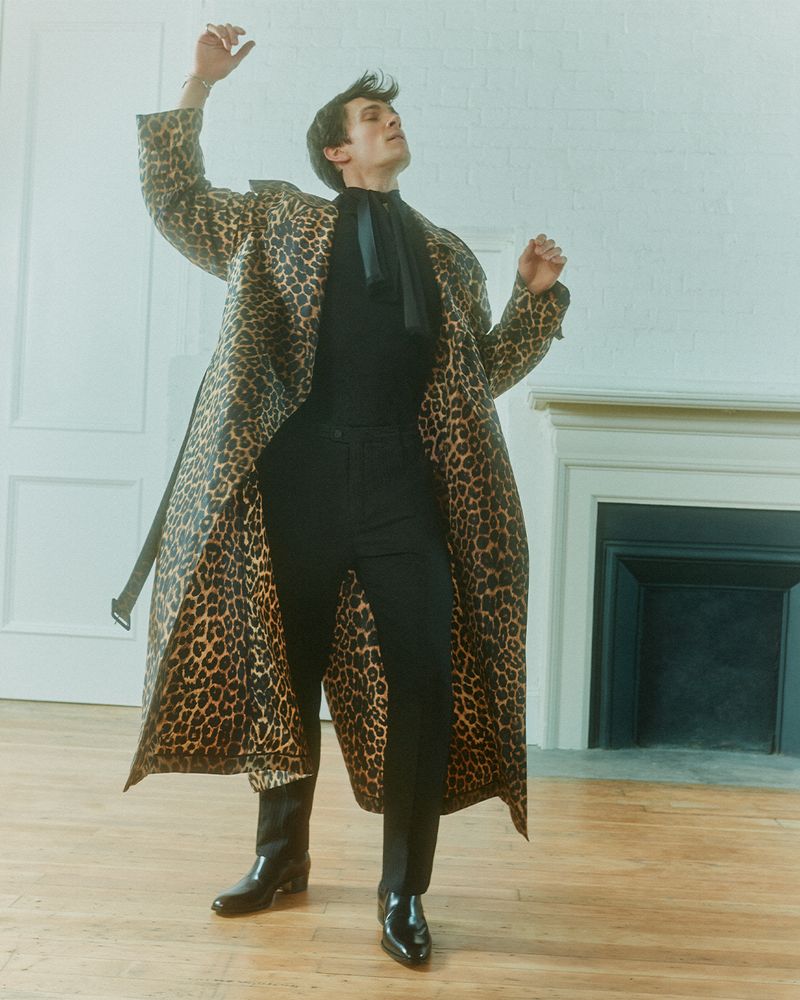

The roles of male ballet dancers are different from those of female. The men’s solo choreography tends to be more bombastic, more focused on leaps and spins and hops and twirls. The women spend a lot of time on their toes in pointe shoes, contorting their bodies into graceful mid-air commas. As such, their bodies tend to be conditioned differently – both male and female dancers are basically all muscle, but women are willowy while the men are, it must be said, hench.

Though Bracewell’s back injury was exacerbated to the breaking point by a day full of partnering, he acknowledges that the ladies might be doing an even more extreme sport than the men. “She’s very much more in the riskier position purely from the injury perspective,” Bracewell says. In Manon, he danced for the first time with a ballerina named Ms Yasmine Naghdi. Near the end of the final act, he throws her, spinning, into the air countless times. It’s both exhilarating and terrifying to watch. “I danced with Alessandra Ferri last season, and she was 60,” he says, of the Royal Ballet, American Ballet Theatre and La Scala Ballet alumna. “You’ve never seen anything like it, she was outdoing us all – completely fearless.

“There’s no reason [ballet] can’t be as popular as really huge sports,” Bracewell says. The “players” certainly train as hard and the competition is just as fierce, if not more so. He’s a pretty good case study for putting more boys into dance classes instead of football training camps. Sure, the money isn’t quite so good, but ballet is certainly more beautiful than the Beautiful Game and the retirement choices tend not to veer into the spending-all-ones-money-and-going-down-in-flames category.

“Some people completely change directions and retrain in psychology, or move into another form of art,” he says. His boyfriend, Mr Andy Monaghan, also a ballet dancer, has become a florist and still dances in a smaller company. “I very much subscribe to the idea that if I’m going to work, it has to be something I feel passionate about and which I love.

“I know there will be some sort of artistic expression in there. Half of me thinks I want to stay in the dance world and push it forward and find out where it can go and make it really relevant and sing its praises.” (Perhaps the first step is to invite more people to the rehearsal peep show.)

“But maybe I’ll say: that was incredible, but I want something a bit quieter…” He pauses. “Or do I thrive on this level of workload and pressure? I think that’s to be discovered, I love pushing myself. I can’t see that stopping.”

Mr William Bracewell performs in Swan Lake on 15, 28 March, 1, 27 April and 11 May; roh.org.uk