THE JOURNAL

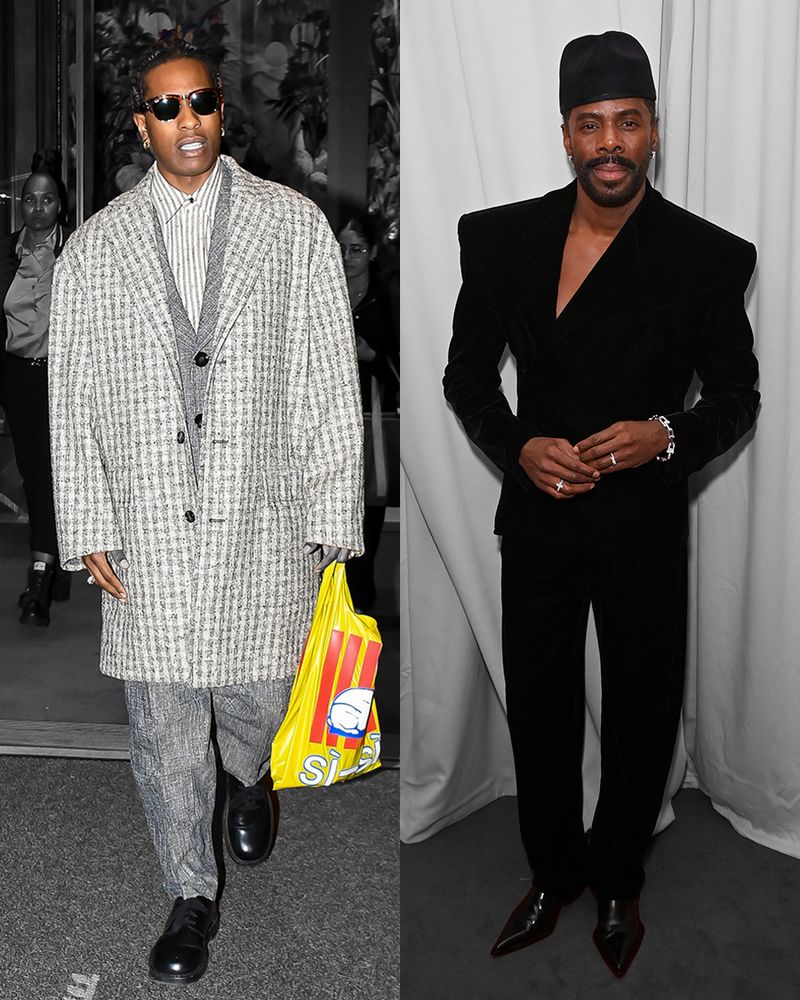

From left: A$AP Rocky in New York City, 4 October 2024. Photograph by Robert Kamau/GC Images via Getty Images. Colman Domingo in London, 16 February 2025. Photo by Alan Chapman/Dave Benett/Getty Images for British Vogue. Jeremy O Harris in New York City, 16 October 2024. Photograph by TheStewartofNY/Getty Images. Pharrell Williams in Paris, 2 October 2023. Photograph by Claudio Lavenia/Getty Images

You may have heard of Beau Brummell and his cohort of cash-rich friends in fitted suits and cravats, gallivanting around Regency London. Who you might not know are all the Black men who jolted the very essence of dandyism throughout history, breaking its codes and infusing it with a greater sense of rebellion. They are the ones celebrated in Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York’s upcoming exhibition, which explores the influence, identity and legacy of the Black dandy, as well as his profound and continuous impact on fashion. And at a time when the style contributions of Black people are so easily forgotten and shamelessly appropriated.

Dapper Dan at the Met Gala in New York City, 6 May 2019. Photograph by Neilson Barnard/Getty Images

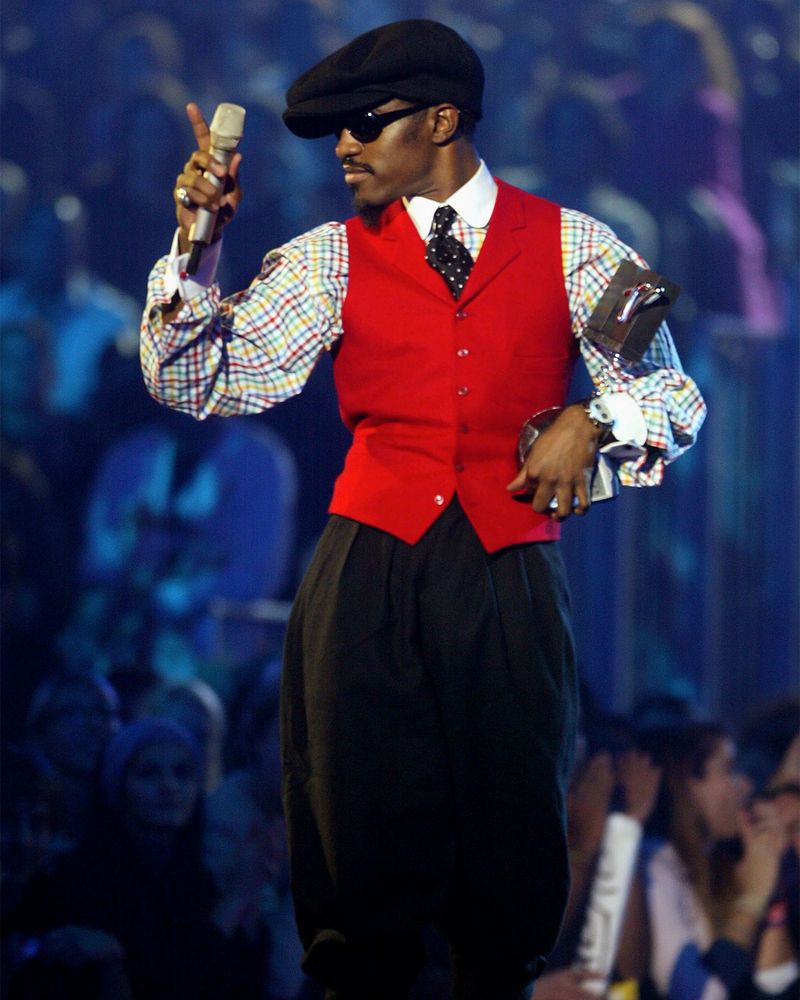

André 3000 of Outkast at the MTV Europe Music Awards in Rome, 18 November 2004. Photograph by Getty Images

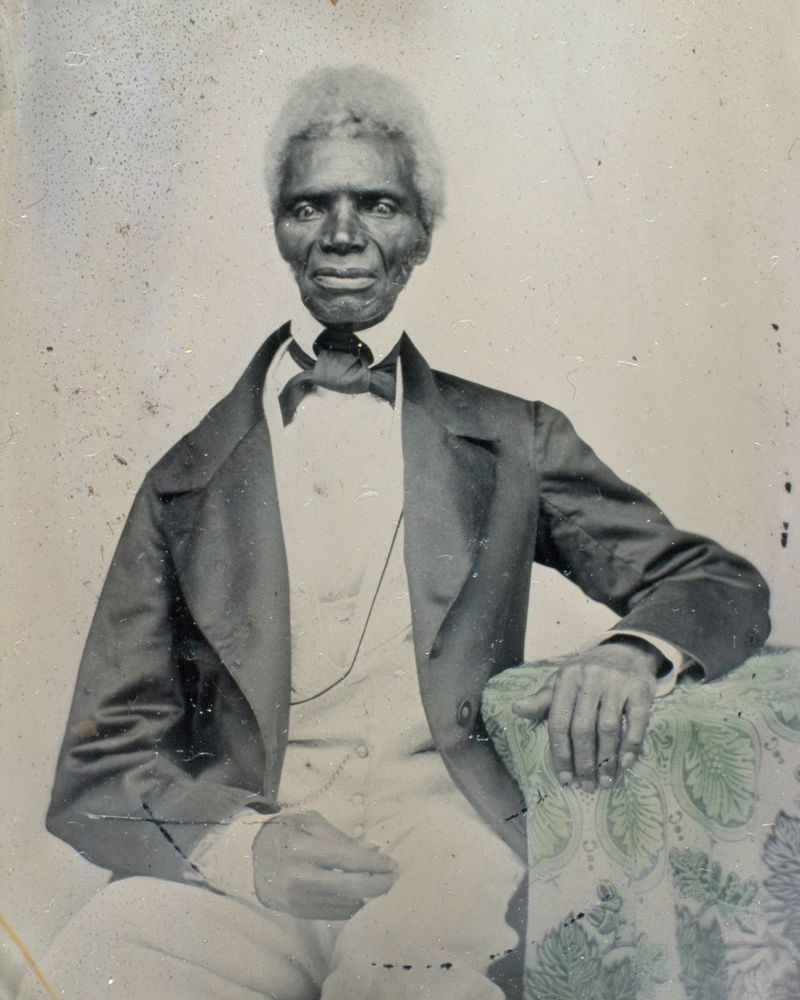

As with many subcultures, it all started with a deep need for self-expression and resistance. The Black dandy was born in the Antebellum South of the US, where enslaved people could only dress up for special occasions, such as weddings and mass. It’s incidentally also the origin of the colloquial term “Sunday best”, to hold onto a little bit of dignity in the house of God.

“The history of Black dandyism illustrates how Black people have transformed from being enslaved and stylised as luxury items, acquired like any other signifier of wealth and status, to autonomous, self-fashioning individuals who are global trendsetters,” affirms the exhibit’s guest curator, the acclaimed author and scholar Monica L Miller.

Self-emancipated Black man named Tom. Photograph by Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 1861-1865

Black dandyism spread globally in the 19th century, with liberated slaves – and their descendants in Paris, London and New York City – using clothing to reinforce their sense of freedom, humanity and taste. The uniqueness of the Black dandy resides in the ability to merge several cultures into one to create flamboyant attires composed of rich and colourful textures and fabrics.

During the Harlem Renaissance in the early 20th century, Black dandies would accessorise their gigantic-lapelled, ultra-high-waisted, wide-legged “zoot” suits like there was no tomorrow. We’re talking fedora hats, tie pins, bow ties, suspenders, silk pocket squares and anything that could provoke a double take. Too much was never enough, and experimentation and pride the central purposes defining Black masculinity. The over-the-topness of the look conferred admiration, yet was often ridiculed with an overt stench of racism.

The movement reached colonial Africa, morphing into its most exuberant form in the Congo region where the Society of Ambiance and Elegance (La Sape) appropriated the style ethos of the Black dandy with ostentatious verve in the early 20th century. This subculture enjoyed a revival from the 1970s and 1980s, with Congolese Sapeurs today regarded as respected style icons.

“Black dandyism is about having a level of pride and flamboyance, with a sense of refinery and a use of luxurious fabrications, colours and textures to solicit attention,” says the visual storyteller Harris Elliott, co-curator of 2024’s The Missing Thread exhibition and 2014’s Return Of The Rudeboy exhibition, both at Somerset House, and co-author of the latter’s subsequent book.

Patience Moutala, coordinator of the Red Devils group and member of La Sape movement, in Brazzaville, 17 March 2014. Photograph by Junior D Kannah/AFP via Getty Images

The celebration of Black dandyism in the Met exhibit salutes a major shift in culture by highlighting the work of pioneering fashion designers, including Dapper Dan, the late Virgil Abloh and Telfar Clemens, as well as the British designers Joe and Charlie Casely-Hayford and Grace Wales Bonner.

“Black dandyism is a powerful reclamation of identity, autonomy and self-expression,” Charlie Casely-Hayford says. “At its core, it subverts societal expectations and redefines what elegance and masculinity can mean. Through sartorial excellence, Black dandies have historically asserted their presence in spaces where they may have been marginalised, using clothing as a form of empowerment and storytelling. It is about the transformative power of clothing, not just as a means of expression, but to communicate identity, confidence and resistance. That is the driving force behind my work.”

Black designers infuse a modern take on tailoring into their work by swinging the rules to incorporate a whole lot of swagger. Up-and-coming names such as the London-based Bianca Saunders and the Paris-based Marvin Desroc, whose vision sit in the lineage of the greats that came before them, are also featured in the exhibit.

“When I started my brand, I was inspired by the dandies around me, my friends and the elegant ways in which they put their outfits together,” Saunders says. “But it wasn’t just about clothes, it was also about their mannerisms and how they express their personalities while removing the care of the European vision on their Black identity.”

For Desroc, Black dandyism style resides in “bold fabrics and eclectic prints matched with English tailoring, which is about surfing on the fine line between traditional dandyism and funk.” To which, sportswear is savvily incorporated today.

“Over the last few years, menswear has undergone somewhat of a renaissance,” noted Andrew Bolton, the curator in charge at the Costume Institute. “At the vanguard of this revitalisation is a group of extremely talented Black designers who are constantly challenging normative categories of identity. While their styles are both singular and distinctive, what unites them is a reliance on various tropes that are rooted in the tradition of dandyism, and specifically Black dandyism.”

Wales Bonner SS23

It has only been five years since the global Black Lives Matter movement erupted, and diversity and inclusion, buzzwords embraced to drive an ideological and structural evolution in Western societies, are being questioned.

“Before Black Lives Matter, there were small-scale conversations about the lack of diversity in the fashion industry,” Elliott says. “George Floyd’s murder changed that and made it OK to have those conversations without them sounding like sub-stories. So this exhibition, which was planned way before Donald Trump won the presidency, is going to end up more political and politicised than it already was as a topic now that the landscape is changing. It will garner more column inches online and in the press.”

Indeed, as the dismantling of DEI initiatives in the US signals a retrogression, the exhibit reinforces the contributions and influence of Black people in socioeconomic and cultural spheres. This recognition is crucial to ensure societal cohesiveness, for being seen, respected and accepted, should be our common purposes as human beings. That is exactly why keeping the essence of Black dandyism alive is paramount – because fashion is political – and the current climate settling in traditionally white spaces will insidiously take us backwards.

To dress is to speak, and Black dandyism speaks volumes at a time when diversity and inclusion are challenged ideals. Celebrity stylists have understood that in a post-Black Lives Matter world, the sartorial expression of their famous clients have a direct effect on the way Black men are perceived. They are key players, whose mission is to ensure the evolution and flourishing and preservation of the movement’s ethos, so that next generations of style aficionados can take ownership of their identity, reshape it and utilise it to convey political values to enrich the global conversation around fashion and luxury.

Today, Black dandyism is akin to a spirit more than a specific look or attire. It’s still, however, rooted in embracing the power of clothing to dare. To defy societal norms and subvert expectations by being unapologetically Black. Hip-hop culture influenced the movement and gave it a new flair by merging streetwear codes with the classical vocabulary, catapulting it to the forefront of the fashion scene.

Black slaves crawled so that the gentlemen of the Harlem Renaissance could walk, in turn enabling A$AP Rocky, Lewis Hamilton, Colman Domingo and Pharrell Williams – all co-chairs of this year’s Met Gala extravaganza – to run, push boundaries. To have fun with clothes on the red carpet and beyond.

Colman Domingo at the Bafta Awards in London, 16 February 2025. Photograph by Max Cisotti/Dave Benett/Getty Images

With Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, the Met repositions the powerful ways in which Black dandyism has shaped not only fashion and style, but culture in celebrating self-expression, sophistication and resilience across the world. The significance of the movement, through cosmopolitanism and creativity, is undeniable and the exhibit contributes to educating audiences by including an undervalued part of fashion’s current identity and history.

“Through a diverse range of media, this groundbreaking presentation will also celebrate the power of style as a democratic tool for rejecting stereotypes and accessing new possibilities,” says Max Hollein, the Met’s Marina-Kellen French director and CEO.

Long live the Black dandy.

Fine and dandy

The people featured in this story are not associated with and do not endorse MR PORTER or the products shown