THE JOURNAL

Illustration by Ms Choi Haeryung

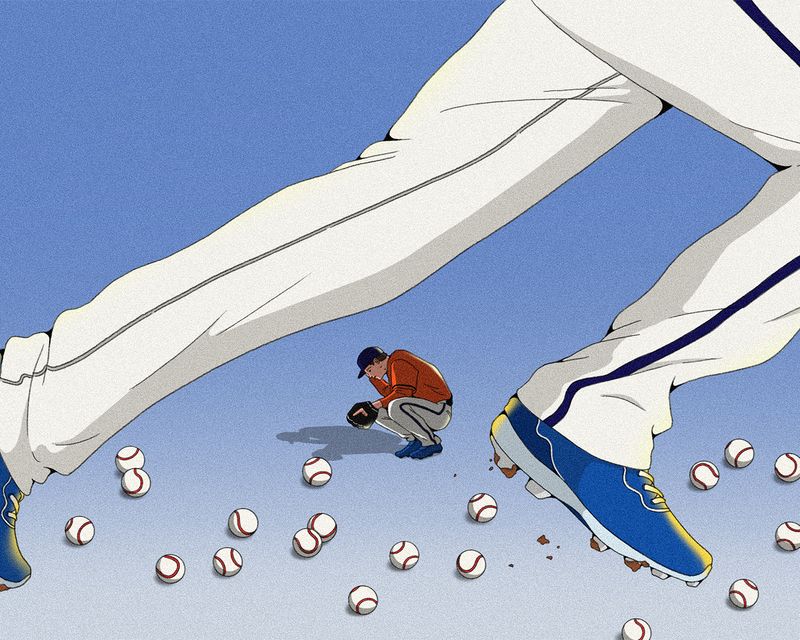

The pantheon of sports stars glitters with tales of icons who, as children, practised relentlessly to hone their skills. Grainy footage of Mses Serena and Venus Williams hitting balls over the net in Compton. Boyish Mr David Beckham crossing the dead ball into the goal. Young Mr Tiger Woods lofting golf balls onto the fairway. These images bolster the myth of the undiscovered talent, finely tuned to deliver sporting success. It feeds a dream that’s corralled by bodies such as the English Football Association (FA) and US National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), who have set up academies and institutes to gather young talent and “hothouse” their potential into elite-level performance.

On paper, it’s a recipe for success. But this is one model of supply and demand with darker consequences. Figures show that only two per cent of athletes playing in organised youth and college sport will ever play professionally. Yet, in the US, an NCAA survey found 64 per cent of Division 1 football players believe it was “somewhat likely” that they would go pro.

That is quite a distance from the reality, and one that’s often bridged by disappointment, as ex-Fulham FC Academy player and Wales youth international Mr Max Noble explains. “I was seven or eight years old when I was taken into Fulham’s football academy,” he says. “I went through the entire system, leaving school at 15 with no GCSEs because there was always this promise of an amazing career.” By the time he was 17, Noble was being given daily painkillers to make it possible for him to train. Then, aged 19, he was “released” by the club.

What followed was depression, isolation, resentment and uncertainty as he realised he was not even qualified to work in a local store. “You feel like you have nothing. I spent my twenties feeling like I’d failed – failed my dad, my family. It’s too much to bear at that age.”

The impact on each individual varies, but following the death by suicide of 18-year-old Mr Jeremy Wisten less than 18 months after his release from Manchester City, football faces a tragic reckoning with this realisation. The inquest into his death found that Wisten had found it difficult to readjust after being released. Shortly after his death, his father called for football clubs to give young people more mental health support. Manchester City is due to make an official comment following internal reviews, but the club’s academy director, ex-footballer Mr Jason Wilcox, has said it would be “extremely negligent” not to review their process and try to make improvements in the light of Wisten’s death.

Part of Noble’s self-prescribed healing process has included creating documentaries that tell his story and that of friends who have also been “let go” by academies. The process has been both therapeutic and galvanising, with hundreds of players DMing Noble to say they recognised their story in his. “The feelings expressed in the messages I’ve received have been almost identical – issues of abandonment, players feeling like they’ve been left with nothing, nowhere to go, no support system from the club, not even a phone call to see how they were getting on.”

Noble eventually pieced together all their stories and turned it into a charter for change. Drafted with law firm FieldFisher, its central tenet is “aftercare”, the idea of a universal system that offers psychological support to every child that goes through the academy system. It’s gained the support of the Labour Party, which has led to positive talks with the Premier League. “We met early in the new year, they said they’re happy to implement almost all of the points, across the board, from July,” Noble says. “That is a massive success to me.”

“You take the most disciplined, purposeful life, with years of success and progress… You are defined by being an athlete and feel special”

Noble has also launched a clothing brand, Certified Sports, to generate funds that he uses to provide psychological support to former and injured athletes. “Being able to talk openly has helped me,” he says. “It’s made me feel less crazy – which was how I felt five years ago. Now I don’t need to seek anything to make myself feel better or forget what I’m involved in because I’m really proud of what I’m involved in. I’m in a happy place in my life now.”

It’s a shift in perspective that sport psychology and mental performance consultant Dr Caroline Silby sees as a key challenge for athletes transitioning to “civilian” life. “You take the most disciplined, purposeful life, with years of success and progress… You are defined by being an athlete and feel special. After years committed to this athletic quest, the struggle to embrace the unknown without athletic participation as an anchor is real. Suddenly athletes must find pleasure in ‘being’ versus ‘achieving’.”

Dr Silby speaks from experience. She’s an ex-figure skater who was part of the US national team and now heads up their sport psychology and mental performance. As an athlete, Silby was lucky enough to count Dr Bruce Ogilvie, one of the fathers of sport psychology, in her support network. “With his guidance, I came to understand that sport was about more than medals and team uniforms. It was about ‘figuring yourself out’, what makes you tick, what gets you engaged and challenged and what gets you motivated and happy.”

That mindset resonated with Mr Lewin Nyatanga. “I focused on the process over the end result, which helped me deal with external pressures,” he recalls. “And I tried hard to always have the thought that I play football, not I am a footballer.”

Nyatanga retired at 29 and baffled pundits who couldn’t understand how the Welsh international, who had played alongside Mr Gareth Bale and held the record as the youngest player to make their international debut, could willingly walk away from the game. “I had achieved everything I set out to achieve and the sacrifices and struggles didn’t seem worth it anymore” Nyatanga says. “I lost my ‘why’.”

Nyatanga now runs his own personal training business and is helping others take a more holistic approach to wellbeing. “I sometimes wish I knew as a 16-year-old what I know now as it would have helped a great deal,” he says. “Instead, I am now paying it forward. We sometimes forget the ‘health’ in health and fitness. A lot of the focus seems to be on how you look and your physical performance as opposed to how you feel.”

Perhaps the hardest change to reconcile with is the abrupt end of a career through injury. It’s a low that Mr Jay Williams experienced after a near-fatal motorcycle accident left him facing years of rehabilitation and ended his career at 21, after only one season playing in the NBA with the Chicago Bulls. Williams, who had been national champion at Duke University, was number two pick in the 2002 NBA draft and had appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

“Beyond birth and death, transitioning out of sport for athletes is perhaps the most significant change they will face”

“In that moment, there’s a level of disappointment because I love basketball,” Williams told The Pivot Podcast. “But it was more that I had put myself in that position to jeopardise not only my dreams, but my parents’ dreams. That was the thing that led me to depression more than anything.

“Also, I was what I did. I was a basketball player. I had never really had any experiences that forced me to think about who I wanted to be, or what I wanted to stand for – I was too busy trying to achieve my goals.”

Like Nyatanga, Williams has since found a way to redefine himself beyond “basketball player”. Today, he combines entrepreneurship and being CEO of Special Events for Rising Stars Youth Foundation with his work as an NBA analyst and radio host on ESPN.

The ability to pivot is testament to an ex-athlete’s resilience. “Beyond birth and death, transitioning out of sport for athletes is perhaps the most significant change they will face,” Dr Silby says. “Interestingly, most transitions – for example, divorce – have an associated anchor for people, such as a job or children. Yet for most athletes, the transition out of sport hits them when they are just getting started on their adult lives. They have not explored other aspects or dimensions of their personality and can feel as though they will never be as good at anything else in their lives as they were at sports.”

Today, Mr Drewe Broughton is one of the UK’s leading high-performance coaches as the founder of The Fear Coach, working with big businesses and elite athletes. Yet, by his own admission, when he hung up his football boots after a career that included more than 500 club appearances, it was bittersweet. “When I stopped playing, I felt my identity was gone,” he says. “I was asking myself: who am I?”

Broughton’s retirement from the game coincided with the Professional Footballers Association referring him to Sporting Chance, the addiction clinic founded by former Arsenal defender Mr Tony Adams. It was the first step in a process that had him “hold up a mirror” and get painfully honest with himself through therapies that included treatment centre addiction recovery, 30-day therapy, inner-child workshops and silent retreats.

“I’ve done a lot of self-work,” he says. “In addiction recovery, they say addiction is a mood alterer. Well, football is the biggest mood alterer I’ve ever had. I’ve tried a lot of things and nothing touches football – playing in front of thousands of people – most of us would never say there is an issue with being a footballer, but I think a lot of players are addicted.”

Broughton brings this realisation back to the need for care of the athletes. “I’ve sat with 14-year-old academy players and said: ‘Put your hand up if you would rather die than not be a footballer.’ All hands start going up and I say that’s good because to do this, you need to care that badly. But we then have a huge responsibility to help these players navigate that pressure. And that is what’s not happening.”

That responsibility is one those involved in the set-up of elite sport, and those of us enthralled with it, could do well with embracing as we collectively push for better care of our athletes during and after their careers. “Communicating to athletes that your support of them is based upon who they are as people rather than how they appear or what they accomplish transforms the pursuit of excellence from a daunting task to a realistic goal,” Dr Silby says. “As members of the sport community, it can be powerful to ask ourselves how we can ‘be’ to consistently contribute to creating culture and community that provides a safe haven for those around us to compete, challenge and change.”