THE JOURNAL

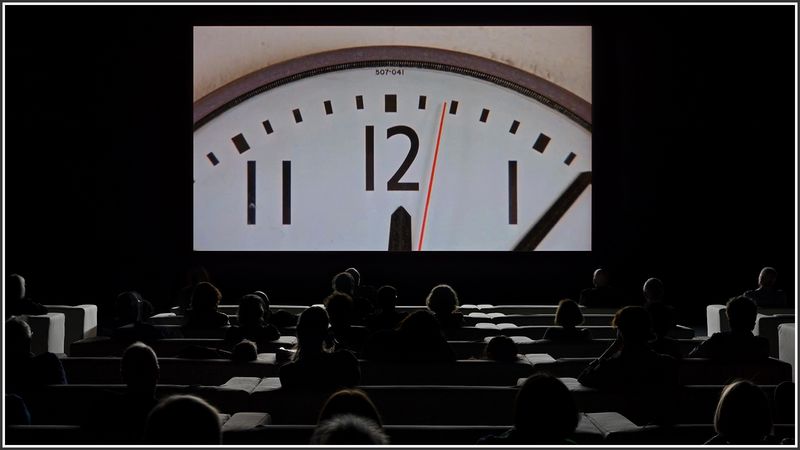

Mr Christian Marclay, The Clock, 2010. Installation view. © the artist. Photograph by Mr Matt Greenwood. Courtesy of The Tate

Whether you drop in for a minute or the full 24 hours, Mr Christian Marclay’s artwork is worth clocking for yourself.

Mr Christian Marclay’s artwork The Clock is a mélange. To sit before its screen – currently installed at Tate Modern's Blavatnik Building – is to witness a full 24 hours of cinema history, all told through a maelstrom of rapidly spliced clips drawn from the archives of arthouse, blockbuster, serial and romcom.

Mr Humphrey Bogart attempts to wake a sleeping woman; Mr Christopher Walken narrates the story of a wristwatch once hidden in his rectum; Ms Joan Crawford (as seems right and proper) drinks a cocktail; Mr Harold Lloyd dangles from the face of a department store; and Mr Tobey Maguire is fired from his job delivering pizzas and forced to rely upon his precarious second job as Spider-Man. The residents of Elm Street prepare themselves for bed, yet their inevitable assailant never arrives. “Life all comes down to a few moments,” says a young Mr Charlie Sheen, awaiting his interview on Wall Street. “This is one of them.”

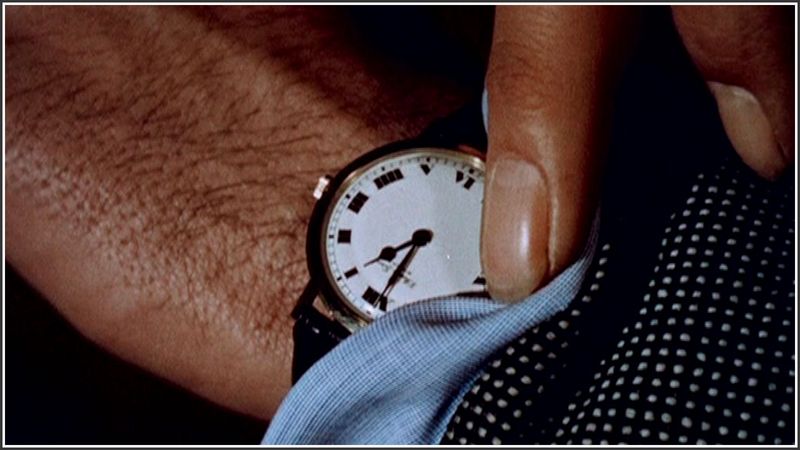

The Clock, which premiered in 2010 at London’s White Cube gallery, is built around a simple premise. As billed, Mr Barclay’s film is a functioning timepiece, faithfully tracking an entire day’s worth of time. Yet it is the work’s execution that delights: the day is measured out in clips that all feature either a clock or watch, each of which is precisely synchronised with real time in the gallery. At 10.50am in the Tate, and at 10.50am on-screen, a delightfully hammy Mr Jeremy Irons makes a phone call. We’re in Die Hard With A Vengeance, and Mr Bruce Willis answers the phone. There’s a bomb hidden somewhere in New York City, and if Mr Willis doesn’t meet Mr Irons’s demand of getting Downtown in exactly half an hour’s time, it will detonate. Meanwhile, visitors to the Tate sit safely in the dark of the gallery, cosied up as Mr Marclay’s artwork breezes past the threat of Mr Irons to continue gallivanting through cinema’s back catalogue. Until, of course, we reach 11.20am, at which point we welcome back Mr Willis.

Mr Christian Marclay, The Clock, 2010. Film still. © the artist. Photograph courtesy of White Cube, London and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

“I saw it back in 2011, but I’d forgotten just how democratic he is in his choice of cinema,” notes Mr Fiontán Moran, one of the curators at Tate Modern responsible for the artwork’s current showing at the museum. “You have clips from Columbo, clips from Deborah Messing’s film The Wedding Date. It really does go across the whole spectrum of cinema. Some people might know romcoms better than arthouse – and vice-versa – so every person’s experience will be different.”

Enabling this is an editing job par excellence – an extended masterpiece as precisely engineered as any mechanical clock. To create the work, Mr Marclay and a team of researchers sifted through thousands of VHS tapes in an act of video-shop drudgery. Trawling the tapes to locate the various times needed for the work must have proven challenge enough, but Mr Marclay has also cut the clips together with finesse. “He is aware that certain hours mean certain things,” notes Mr Moran. “Because midnight has a certain quality, for instance, the edit of the film changes at that time. It becomes a lot quicker, whereas at 3.00pm the edit is maybe not so dramatic. It’s something that is dictated by how cinema deals with time itself.”

The artwork was acquired by the Tate in 2012, in partnership with Paris’ Centre Pompidou and Jerusalem’s Israel Museum, but it is only now that the film has been able to screen at the London space. “It has to be shown in a very specific setting, and we didn’t actually have the right sort of space to show it until they built the Blavatnik Building two years ago,” explains Mr Moran. “Even though it’s a video piece, it’s very much made as an installation and it’s a communal experience. Once you’re in there you can spend longer than you would ever normally spend in a cinema, or perhaps shorter.”

Mr Christian Marclay, The Clock, 2010. Film still. © the artist. Photograph courtesy of White Cube, London and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

While few will ever see Mr Marclay’s work in its entirety, this is no barrier to the work’s enjoyment. “You don’t have to see the whole thing,” says Mr Moran. “There is no big reveal at midnight and it’s OK not to see everything. It’s more about your own personal experience, but it’s also an interesting record of the vast number of things that can happen within 24 hours. While someone might be having a great time at a party, somebody else is trying to stop a bomb going off, and somebody else is rushing to work. It’s a great testament to that variety, and the thing that unites the experience is very much an awareness of how people spend time.”

As part of the work’s debut at Tate Modern, the museum has organised a series of 24-hour viewings of the film (“If people go out to a club they can stagger in on their way home – if they wish,” notes Mr Moran), which will enable visitors to experience aspects of the work typically hidden behind museum closing times.

“Since the work was made, cinema has changed dramatically,” explains Mr Moran. “Most people will now very often watch things on their laptops or through Netflix. It’s a very different viewing experience to the history of cinema or TV that The Clock charts, which is very much a collective history from when people were used to going to the cinema or renting videos.” While the format of The Clock’s rapid cuts and meme-like snippets has found fresh currency as the lifeblood of social media and YouTube, Mr Marclay’s work is a more physical and substantial experience. Within The Clock, there is no option to fast-forward or repeat, and no ability to skip to the next clip: everything simply flows at its own pace.

Synchronise watches