THE JOURNAL

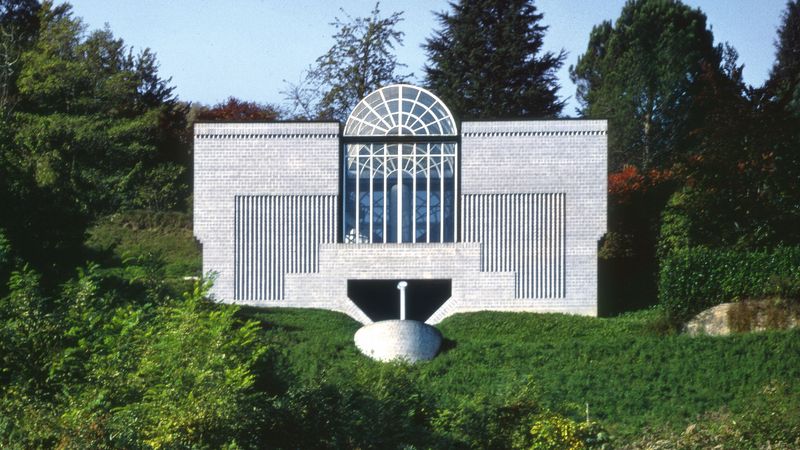

Residence in Origlio, Switzerland, by Mr Mario Botta, 1982. All photographs courtesy of Thames and Hudson

Meet the rule-breakers who defined mid-late 20th-century design.

“Postmodernism is the most provocative, most controversial, most varied and least understood term in the panoply of 20th-century design.” Thus Ms Judith Gura sets out her stall in Postmodern Design Complete, her splendidly comprehensive survey of postmodernist design. Postmodernism, Ms Gura notes, may have been the darling of 1970s and 1980s architecture and design, but pinning down with any precision what it actually was is a fraught business. The essential problem is one of variation. There are numerous postmodernist designers (although, curiously, few will today admit to having been disciples of the movement), but most are little like one another. Despite having been the scourge of rationalists and functionalists the world over, postmodernism itself was a sweated-down hotpot of disparate ingredients: a preference for everyday materials, a desire to collage historical references, an anarchic use of pattern and colour, and a healthy disregard for the strictures of modernism, to name just a few. From within this mélange, considerable variety could be found. To mark the release of Postmodern Design Complete, MR PORTER is delighted to share its guide to three of the movement’s most genre-bending practitioners, all of whom feature in Ms Gura’s masterful overview.

Mr Hans Hollein

Retti candle shop, Vienna, by Hans Hollein, 1966

Replete with a sly surrealism and a delight in visual puns, Mr Hans Hollein’s architecture and product design are a Dada-suffused joy. His Retti candle shop in Vienna has an aluminium façade with a stylised cut-out doorway that can be read as either the silhouette of an ionic column or a resplendent phallus beckoning the visitor inside, a curiously fitting entrance for a shop in the city Mr Sigmund Freud called home. Indeed, this interest in classicism and flair for irony-laden historicism was typical of Mr Hollein, who eschewed the knockabout aesthetics of much postmodernism in favour of a more refined architecture that nonetheless moved the discipline on from the constraints of modernism – an approach that won him the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1985. Telling of Mr Hollein’s lightness of touch was his decision to pursue his education in the USA, where he studied under and met past masters such as Mr Mies van der Rohe, Mr Frank Lloyd Wright and Mr Richard Neutra. While there, Mr Hollein opted to drive around the country in a second-hand car, determined to visit every town in the USA called Vienna. For the record, there are seven.

Mr Shiro Kuramata

“How High the Moon” armchair, nickel-plated steel mesh, edition of 30, for Vitra International, by Mr Shiro Kuramata, 1986

The difference between modern and postmodern design is sometimes explained as the difference between objects that reveal their making process and those that obscure it. If this is the case, then Mr Shiro Kuramata’s design is a fine example of the latter style. His 1976 Glass Chair is a series of solid glass slabs glued together in such a way that the structure appears impossibly delicate. The 1986 How High The Moon armchair borrows the form and scale of a classic club chair, but is executed in a steel mesh that leaves its form airy and gauze-like. For his celebrated Miss Blanche chair, he encased imitation roses with a transparent Lucite frame, transforming the piece into a kind of frozen floral aspic. While other postmodernists obfuscated through a superabundance of ornamentation, clashing historical references and decoration run amok, Mr Kuramata’s use of material, colour and form was quieter. His work treated processes and materials with a straightforward honesty. The complexity of his objects, and the sense of disbelief they provoke in the viewer, was entirely down to the originality and daring elegance of his ideas.

Mr Mario Botta

Residence in Origlio, Switzerland, by Mr Mario Botta, 1982

When is a postmodernist not a postmodernist? When they are Mr Mario Botta, of course. A former assistant to arch modernist Le Corbusier, Mr Botta’s work eschews the kind of play with colour or explicit historical sampling that defined many of his contemporaries’ designs. Instead, he favours robust geometrical forms and monochrome patterning, as in his celebrated 1995 SFMOMA building in San Francisco, a red-brick, stacked box construction organised around a zebra-striped oculus. Indeed, within Mr Botta’s oeuvre there are numerous features that might lead one to mistrust the appellation “postmodernist”. His furniture designs for brands such as Artemide and Alias employ tubular steel and spare forms that tip their hat to Bauhaus, while his architecture has little of the improvisational quality that defines many postmodernist buildings. The architecture critic Mr Paul Goldberger once described Mr Botta’s buildings as “self-assured essays in geometry”. Nonetheless, it was no less a figure than Mr Charles Jencks, the theorist who initiated the use of “postmodern” within design and architecture, who saw Mr Botta’s work and its frequent use of traditional masonry as a fine example of “postmodern classicism”. Mr Botta himself, however, is less than keen to be labelled, having previously dismissed postmodernism as an “anything goes” movement that led to a profusion of “global Disneyland-architecture”.

Postmodern Design Complete by Ms Judith Gura (Thames & Hudson) is pubished on 28 September