THE JOURNAL

Illustration by Mr Jori Bolton

They exited their cars two by two, like the animals coming off The Ark. Some people in Ubers, others in large saloon cars driven by harried-looking chauffeurs. No one came on the bus. But then this was Mayfair in February 2022.

By the time we reached the entrance to the party on Grosvenor Square, I could already feel the light twinges of disquiet, a certain excitement, but still that chill hand of anxiety knotting up my stomach. I felt like a stranger in a foreign land, which was absurd – I’d spent so much time at so many parties in this bit of London.

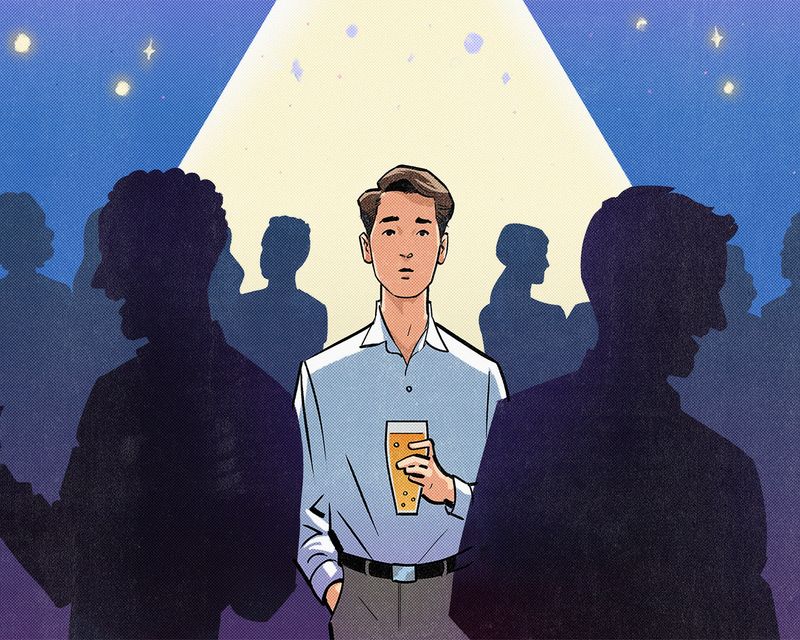

We pressed on beyond the people with iPads taking names at the door, and then down the big marble staircase. Suddenly we were navigating the crowd: everyone was shuffling and pushing and waiting and drinking to a back-beat of air kisses and shouted hellos. “How nice to see you again, darling… It’s been years. Oh, you do look well.” It was at this point that I decided to get a very strong drink and drink it very quickly. It occurred to me that I hadn’t been around this many people, so many strangers, for the last two years.

During the pandemic, we had packed up and shipped out of London, swapping a Hackney flat for a rickety cottage in the country. We went from spending most nights at parties to wearing slippers and stoking a log fire. Like the rest of the country, we began to see strangers not as sources of fun and interest, but as vectors of disease that threatened to put us out of action and into quarantine. It was “stranger danger” all over again, except that now it wasn’t about accepting Werther’s Originals from men in rain macs, but avoiding absolutely everyone.

After so long in isolation, can we go back to our old selves – our more friendly, better personalities that we save for the outside world? What happens when we lose the knack for connecting with people we don’t know? It’s these questions that form the bedrock of a recent book called Hello, Stranger: How We Find Connection in a Disconnected World by Mr Will Buckingham, who is something of an expert on meeting strangers. His book tells of the experience after his partner died, and how he sought solace in travelling to different countries – from Myanmar to the Balkans – recounting the many pleasures and pitfalls of meeting people along the way.

“What is interesting about interacting with strangers is that sense of not knowing what is going to happen… But also there’s that opportunity for newness and new possibilities”

One thing Buckingham is very clear-eyed on is that the fear of unfamiliar people is not insuperable. And how overcoming that fear can lead to enormous pleasures. “What is interesting about interacting with strangers is that sense, when you meet somebody, of not knowing what is going to happen,” he says. “This is why strangers can be slightly alarming, but also there’s that opportunity for newness and new possibilities that comes with unfamiliar people, because your world and the stranger’s world are necessarily not the same so when they meet your world has to open up and you can conceive of new possibilities that didn’t exist before. That is the pleasure.”

What about social media? Has it proved itself a useful means to meet and interact with new people, or has it just entrenched mutual suspicion of the other? Both, says Buckingham. “Twitter, for instance, has opened up the possibility for connecting with people and finding communities, so there is definitely a very strong positive side to that,” he says. “But there is also tribalism. I suppose that the oppositional nature of Twitter can lead to divisions becoming entrenched and that is obviously a huge problem.”

Buckingham doesn’t, however, suggest throwing open all the doors to your life. “What I would suggest is giving that desire to connect more space – let your curiosity come out a little more. Try small experiments to open up a little bit more – and see what happens if you don’t allow fear to win out,” he says.

In the book, he suggests playing with that mixture of fear and curiosity and seeing where it gets you. As he points out: “There are 8 billion people on the planet and we each tend to know on average about 150 of those people at most. So, you are not going to run out of people to practise with. There is simply no way to keep strangers at bay, so why try?”

Back in Mayfair, I bump into an acquaintance I haven’t seen for years. They then introduce me to their friend and a whole domino fall of acquaintanceship is made in that large dark room. At first it feels a little strange, a touch trying. It is a matter of being out of practice. Years of isolation, I suppose, do have that effect. But I persevere. As Buckingham makes clear – you can’t just expect to naturally find that sense of friendliness, you have to cultivate it, you have to take the social risk that is endemic to all interactions. And so I do. And, you know it feels good, it feels like a gamble that has paid out. Buckingham is right and I’m glad for his advice.

I leave an hour or so after I arrive, a little taller, a little more confident and a little more my old self. Though probably with a headache on the way in the morning.