THE JOURNAL

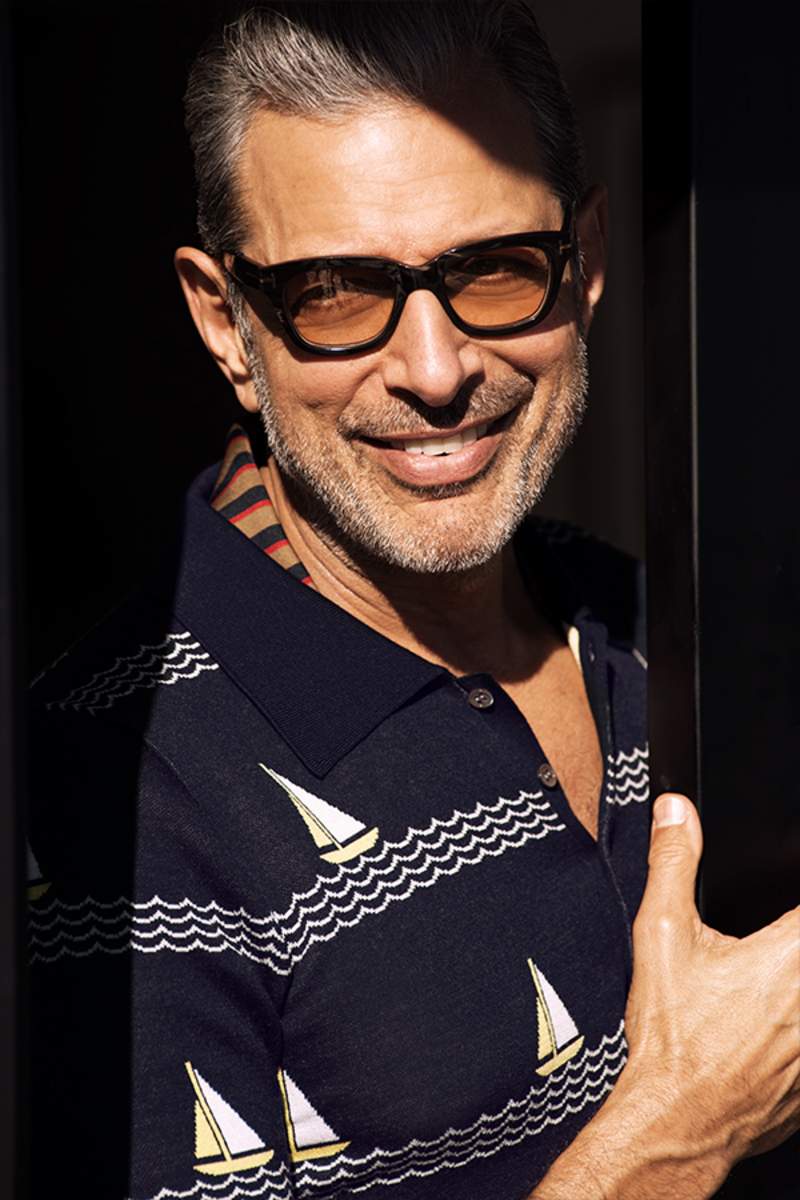

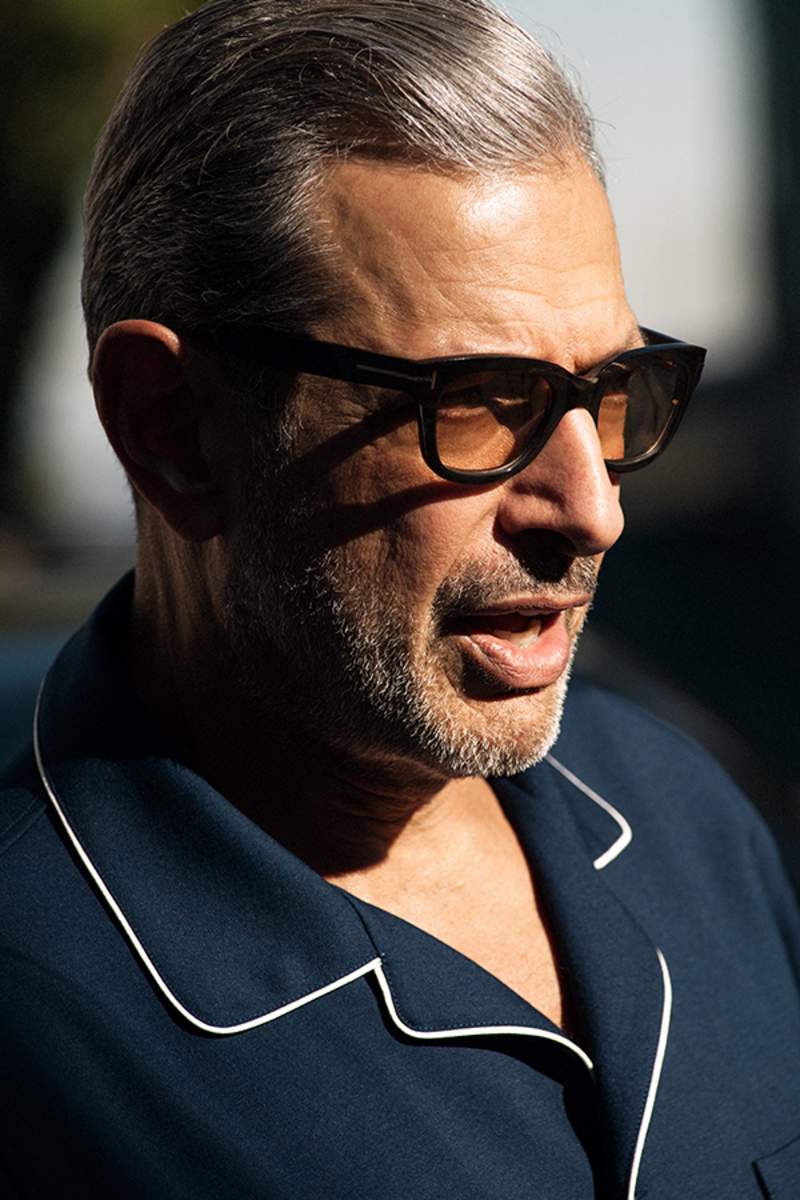

Mr Jeff Goldblum is less of a 64-year-old man than a 6ft 4in happening. And, on the balcony off a mid-century modern living room somewhere in the Hollywood Hills, flooded with enough whiskey-hued light for a Rat Pack drinking session, he is happening before our very eyes. Sockless on set in loafers, a polka-dot suit and a “barely there” tie, his hair is an impeccable whoosh of silver-grey somewhere between vintage pewter and arctic fox. He has the kind of drug-free euphoria of a man who has just woken up from a power sleep and found himself 20 years younger.

Mr Goldblum is the surprise new poster boy for style-conscious sexagenarians. “Yeah, I feel like I’m blooming right now. I’m very much like a pregnant woman,” he mumbles. Goldblumian ruminations are sound-pockets of sheer charisma. “I’m enjoying life no end, and more and more as we go along. And I feel like I am getting better at things. I have palpable results.”

“I certainly like to improvise, challenge myself. I consider myself a student”

Mr Goldblum less responds to questions than takes you on a kind of free-wheeling, wow-inducing Beat road trip. He takes “living in the present tense” quite literally. It’s a rollercoaster joyride, paced by alternating stumbling, stuttering, grappling and tsunamis of eloquence; his pupils buzz like bluebottles searching for the next idea upon which to land.

He is a man so singular, he has turned being himself into an art form. From his “I am an insect who dreamt he was a man” speech in Mr David Cronenberg’s 1986 cult sci-fi thriller The Fly to his Holstein Pils lager ads in the 1990s, he is the master of the monologue, always, seemingly, giddily improvised as if a chain reaction of epiphanies were happening in real time. His offbeat performances, maladroit magnetism and unique talent for the indefinable grey zone between humour and gravity made him an oddball leading man. His talent has often been overshadowed by the sheer CGI magnitude of some of his films (Mr Goldblum has a knack for box office gold – Jurassic Park and Independence Day were two of the most financially successful blockbusters of the 1990s). But his transformation from the geeky Seth Brundle, a man whose humanity is dropping off along with his body parts, into Brundlefly has the brilliance of Mr John Hurt’s Elephant Man. Post-millennium, his shamanic eccentricity has made him a natural muse to Mr Wes Anderson, with turns in The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou and The Grand Budapest Hotel. Yet he seems to have avoided the quicksand of self-parody. There is something fluid, shape-shifting about Mr Goldblum; he’s both indisputably himself and ever-evolving, improving.

Riffing on… Tonight, he is playing his weekly slot at The Rockwell in Los Feliz, with his jazz quartet The Mildred Snitzer Orchestra – named after his mother Shirley’s friend who lived to 100 years old. An accomplished pianist, he improvises in each set, every one of which is kept secret from him by his own band. He likes to be kept on his tapp-y toes. In 1995, he directed a short film that was nominated for an Oscar called Little Surprises – a phrase which has become his mantra. For Mr Goldblum is a yogi in a jazz body: if he wrote a self-help book right now, it might be called Zen And The Art Of Piano Keys. “I certainly like to improvise, challenge myself. I consider myself a student.” He has turned his acting training in the 1970s, an offshoot of Stanislavski's Method under Mr Sanford Meisner, not only into an improvisational musical method but a kind of all-embracing life philosophy. “Meisner said, ‘If you work constantly, it’s going to take 20 years before you can even call yourself an actor.’” That’s the way it is with piano, with everything, he says. “That’s how organic and slow-cooking this process is. It’s not any microwave effort.”

The slow-cooked Mr Goldblum is a sophisticated dish. In addition to all the jazzing, he has become the surprise master of distinguished, achromatic dressing. It helps that he is an enviable mix of stature, brawn and lank with the torso-to-leg ratio of a king crab. Currently, he’s all brainiac beatnik in Tom Ford horn-rims, and biker jacket and classic lace-ups by Saint Laurent. It’s all a long way from his 1980s Hasselhoffian days. And there are more comely improvements. Time, and a beard, have better balanced the dynamics of his face: the intense eye contact and fleshy lips were once almost too overpowering for a youthful complexion and under-pronounced chin. The Spock-like ears that somehow suggest a higher intelligence – and had him cast as series of apocalypse-defeating scientists – now seem less nerdy, more at home with six decades of experience.

And if I had worried this might turn into a Goldblumian version of a Mr Robin William-style performance interview, complete with competitive lexicon, I was wrong. There is an underlying steadiness to Mr Goldblum. “I like to extemporise,” he says, balancing a plate of lentils and black rice on his knees. (This rather cramps his hand-gesticulating. Mr Goldblum is fascinated with hands: he likes to examine other people’s upon meeting. As a precaution, I am freshly manicured.) “But I value the whole lost – but recoverable, important, spiritual – portal of deep listening.” Not only to me, he says. “But to the buzz of the silence in the room.” This is delivered in such deep, hypnotic tones that I feel like I’m listening to a meditation tape.

“Well, I like a spontaneous, vibrant… life. But a lot of that is up to me. You can’t expect doves to fly out at every moment”

Last night, he even discovered a new method of meditating. “I tell you, I had the best bath I ever had.” There follows a meandering account of being in the tub with his “delicious and adorable” infant son Charlie Ocean, which takes in his child’s new realisation that soap shouldn’t be eaten – “I think he kind of understood that in a more refined way.” It is so gorgeously delivered that I don’t care that it takes 15 minutes. “Having Charlie Ocean is a continual opportunity for surprise. The talent is having a childlike wonder of any moment no matter how small.” Having his first child at the age of 62, he tells me, has been a catalyst for his autumnal renaissance. “Every day is a kind of a creative adventure.” Charlie Ocean is Mr Goldblum’s toughest crowd. “Even if he knows a joke that I do. It’s got to keep growing, evolving.”

Charlie Ocean’s mother is 33-year-old Canadian gymnast Ms Emilie Livingston, a Pan-American champion in rhythmic acrobatics who competed in the 2000 Olympics. She is now an aerial acrobat and contortionist, and from her showreel on YouTube, we can see she’s universally double-jointed. Oh, and she speaks French. How did he woo her? He befuddles around, coy with a goofy grin. “Oh, I don’t know. I guess I got lucky…” He says he met her at his local gym on Sunset Boulevard doing “a remarkable headstand”. (They married in November 2014; Charlie Ocean was born, rather serendipitously, on Independence Day the following year.)

Mr and Ms Goldblum call each other Peaches and Patches (something to do with his sketchy chest hair) and share a love of music. Mr Goldblum does an hour of singing and piano on his Fender Rhodes or his Yamaha Baby Grand every morning – often with Charlie Ocean perched on his lap, wearing his father’s pork pie. Music is his “tonic”; his singing, a kind of elixir of youth. “Peaches has a wonderful voice. We sing together. And I always catch her humming in the shower.” And an aerial acrobat must be the perfect match for a man who likes surprises. “Well, I like a spontaneous, vibrant… life. But a lot of that is up to me. You can’t expect doves to fly out at every moment.” Nor your wife to descend from the ceiling on a rope, I say. “No, even if she can and does. She has a rig at home. She constantly surprises and entertains me.”

There have been other enlightenments in the last year. He has had to accept The US’s new president-elect, for instance; Mr Donald Trump was more than a “little surprise” to Mr Goldblum, a staunch Democrat. He campaigned for Ms Hillary Clinton in the swing state of Ohio. The loss was “painful”, he says. Climate change is the “issue” at the forefront of his mind. He’s just watched Mr Leonardo DiCaprio’s documentary Before The Flood. Fortunately, if it comes to it, Mr Goldblum is good in an apocalyptic crisis, at least in his films. He seems to have a keen sense of the fragility of our lives on Earth. His elder brother, Mr Rick Goldblum, died of kidney failure at 23 when Mr Jeff Goldblum was 19. “None of us live forever. Even if you live to 100 in the cosmic calendar, that’s a blink of an eye. I’m open to living, but I’m open to dying, too. Monks sometimes meditate in morgues. It’s all very fleeting. We will be here and not here.”

“Having my son is a continual opportunity for surprise. The talent is having a childlike wonder of any moment no matter how small”

Mr Goldblum was born in 1952 into a Jewish family in West Homestead, a suburb of Pittsburgh. His father, Dr Harold Goldblum, was a doctor who had dismissed his own thespian urges in boyhood. His mother, Ms Shirley Goldblum, was a former radio broadcaster. One of three children, Mr Goldblum took piano lessons from an early age and, as a teen, secretly looked up cocktail lounges in the Yellow Pages, and called around for pianist vacancies. But being a jazz musician was secondary to his big dream: every morning he wrote, “Please God make me an actor” in the condensation on the shower door. At 19, he moved to New York and enrolled in Mr Meisner’s classes at the Neighborhood Playhouse where alumni included Messrs Dustin Hoffman and Sydney Pollack. It was 1970 – quite a year to move to the city. “But I wasn’t such a nightlife person. I was loose enough in my own way. I got involved with yoga and Eastern philosophies early on and was interested the therapeutic aspect of acting.” In 1971, the year his brother died, Mr Goldblum took mescaline a few times, and LSD once. “It made me think in spectacular and miraculous ways, but it was brain messy. I wanted my full wits about me. I was very serious about acting.”

He got his first break in the chorus of the Broadway rock musical Two Gentlemen Of Verona, and lost his virginity at 18 on opening night, “a double whammy”. He moved to California in 1974, where he was cast by Mr Robert Altman in California Split and Nashville, and by Mr Woody Allen for a Hollywood party scene in Annie Hall, and enrolled in a number of self-awareness courses. “After which, I sat down to real therapy. I have seen a wonderful woman for the last few decades, Luanda, who I’ve sought out at landmark passages in my life, like getting in and out of relationships.” (He has been married to Ms Geena Davis, and thereafter spent 20 years dating a litany of beautiful women, including Mses Laura Dern and Lydia Hearst.)

Mr Goldblum was once called “a Wagnerian superlover” by an American critic. “Maybe vulgarian, but nothing Wagnerian or even super,” he chuckles. Ms Livingston was “cautious” of him at first: “She’s not a casual type.” And before meeting her, “he wasn’t ready” to become a father, but, when she brought up having a baby, after the relationship got serious, “I thought: the way she is saying it – it isn’t untrustworthy. It didn’t make me feel like she had some agenda.” He suggested they talk it through with Luanda and did for a year. She officiated at their wedding.

He is “more equipped to be father” now he is older, he says. He enjoys the domestic routine of nesting, which means they are in bed by 9pm every night and up at 6.45am. When they are not on their side-by-side treadmills at their gym at home, Peaches and Patches are singing, grocery shopping or hanging out with Woody Allen, their red-haired standard poodle. It’s all about simple pleasures. Despite lucrative blockbusters and commercials work, Mr Goldblum is not a man who has ever choked on his bank account. He is learning to live, he says, with “less and less stuff”. So he’s a Buddhist in Saint Laurent, I tease. “My clothes are very pruned down.”

He must feel sartorial pressure being in the Mr Wes Anderson gang. “On The Grand Budapest Hotel, we all took over a wonderland of a hotel in Gurlitz in Germany, over the border from Poland, in midwinter. We all had dinners together every night. Wes is like Robert Altman in the way that the process of shooting is like an art piece in itself.” Mr Goldblum is working on Anderson’s new project, “a stop-motion film about dogs” in the vein of Fantastic Mr Fox, also voiced over by Mr Bill Murray (surprise, surprise) and Mr Bryan Cranston. But his next release is Thor: Ragnarok, out in January. Rather fittingly, he plays Grandmaster, the oldest and wisest cosmic being in the Marvel universe.

Mr Goldblum has been around, but he’s not the kind of old Hollywood jazzer who reminisces about erstwhile cronies. In the Goldblumiverse, there is always someone new to be excited about. This summer, he went on a “boat trip” organised by Microsoft’s Mr Paul Allen to Vietnam and Malaysia for 10 days, along with Mr Stevie Wonder and Ms Chrissie Hynde. Also there was Mr James Watson, now 88, one of the duo who unravelled DNA in 1953; Goldblum played him in 1987. “When I saw him, he said, ‘I didn’t want you to play me in the movie. I wanted John McEnroe.’ Someone said maybe he meant John Malkovich, so I suggested this and he said, ‘No, I mean McEnroe. You remember there was a scene where you played tennis? He would have done a better job.’”

This weekend, he and Peaches are attending an honorary event at the John F Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts along with Mr Al Pacino and the Obamas. “I’m cherishing every last day of his presidency. I can’t imagine the Herculean effort it’s taken to do everything he’s done.” He’s also jacked up about seeing Mr Pacino again. “Oh, Pacino. What a man!” They’ve never worked together. But perhaps they will one day, I say; I mean, in Weisnerian terms, Mr Goldblum’s only just qualified for the job description: “actor”. As he puts it, “I’ve got miles to go before I sleep.” Suddenly, it’s as if he’s just coming up on a double espresso. I would like to run his sweet riff in full, but alas, you know, suffice to say, it kind of, you know, ends like this: “…and I feel like I’m on the threshold of something, you know? My best work. I just feel I, I, I… might be able to do something better than I have ever done.” And tonight, he will play the best jazz piano of his life.