THE JOURNAL

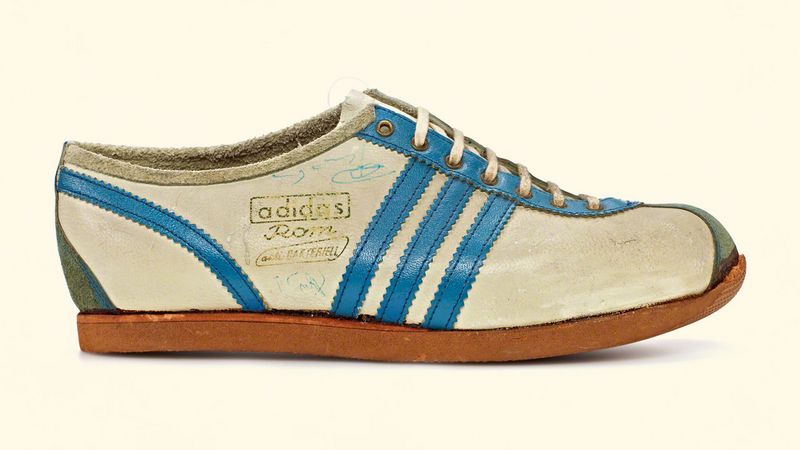

Adidas City Series Rom, 1960. Photograph courtesy of adidasArchive/Studio Waldeck

This month sees the release of the Malmö Net Spezial, the latest iteration of the long-running adidas City Series – an adidas range featuring individual shoes with discrete designs named after and inspired by international cities. In the technologically advancing, hype-driven world of modern sneakers, for any shoe collection to still even be available while deep into its seventh decade is a remarkable achievement. For it to be relevant, still upgraded and eagerly awaited by collectors is even more so.

Less a conventional pack and more a sprawling family of shoes, the multiple versions of the City Series have given it an almost unrivalled flexibility and longevity. And while they have perhaps been less celebrated and acclaimed than other headline-grabbing models, much of what we now think of as the norm in trainer culture, design and releases was first established by these shoes and the designers behind them.

The story of the City Series goes back as far as the Rom (or Rome), a training shoe released by adidas in the late 1950s in an Italian-style blue-on-white configuration ahead of the 1960 Olympics in the country. “Nothing much really happened with other city releases until about 1968, when the brand changed the name of its Jaguar sneaker to ‘Athen’ for the Mexico Olympics, paying homage to the birthplace of the modern and ancient games,” says Mr Jockey Wyatt, founder of Liverpool’s Transalpino store and label and a longstanding vintage dealer. However, these early, sporadic releases would kickstart a series of shoes in the following years, a variety of sneakers with the same low profile and simple design, each modified and individualised for each great city they namecheck.

“The City Series was not actually created as a series of shoes,” says Mr Bobby Mac on the topic of the somewhat ad hoc roots of the shoe. A trainer collector, consultant and archivist, he has worked on a series of adidas exhibitions in Manchester and Blackburn, the Laces Out trainer expo and the ZX: Roots Of Running book, as well as a volume focused solely on the City Series. (He also had a shoe, the McCarten SPZL, named after him in 2017 as part of adidas’ sought-after Spezial line of new models inspired by deep archive pieces.)

Adidas City Series Athen, 1985. Photograph courtesy of adidasArchive/Studio Waldeck

“Early 1970s, you had rare shoes like the Kingston and Vienna,” Mac says, detailing the period when the individual shoes fully coalesced into a definable range. “Adidas then produced a shoe to coincide with the 1972 Munich Olympics called the München 72. The Athen were produced alongside other low, flat suede shoes such as Tobacco – named after Tobacco Caye, a tiny island in Belize – plus other low suede shoes like Trimm Star and Mexicana. This was all gearing up to the start of the European city models, the shoes that we now call the City Series: shoes like Brüssel, Malmö, Stockholm, Bern, Dublin and Berlin to name a few.”

Mac points out how exotic they would have looked to UK consumers at the time compared to the rest of the market. “These shoes had clashing colourways, bright orange leather stripes on velvety black suede, yellow on blue, blue on yellow, orange on blue, greens, reds and so on. They would have really stood out in a sports and leisure shop amid the brown shoes, cricket bats and hockey sticks.”

Back then, most brands were still largely thinking of their sports shoes purely in terms of athletic function and expanding into mass production. Meanwhile, adidas were early on the trends which have come to dominate footwear to the present day – individualisation, localisation and limited availability. “It was one of the first series that used localisation as the key theme,” says Mr Joss Long, sneaker buyer at MR PORTER. “It gave communities and cultures a shoe that was truly theirs, representing their city in name and aesthetic.”

From early on, the shoes were associated with discerning football casuals, especially in the north of England. “The first City Series shoe worn by terrace lads would have been the München with the Trimm Trab sole unit, which were originally brought back to these shores when football fans headed into Europe following their teams,” says Wyatt.

Adidas City Series Vienna, 1964. Photograph courtesy of adidasArchive/Studio Waldeck

Other collectors point to the Stockholm and Montreal as key shoes in their areas at the time. Mr Dave Hewitson of the 80s Casuals label and author of The Liverpool Boys Are In Town highlights how the recession gripping Britain in the early 1980s meant sports retailers commonly favoured cheaper adidas models such as the Mamba and Nastase. Young British football fans were only alerted to the existence of more expensive and hard-to-find models by trips to European fixtures (specifically Liverpool’s clash with Bayern Munich in 1981, which took thousands of English fans direct to the home of adidas).

The München quickly became a sought-after, more elitist alternative to the cheaper, more readily available models in the UK. “We did not know about a European or a North American ‘City Series’ of trainers,” says Hewitson of the time. “No internet, no books on the subject and no advertisements on TV meant we bought what we liked. We made our own choices and the München just seemed to fit in with that period.”

Where they can still be found, these original models have proved to be highly coveted collectors’ items. “As a vintage retailer, the main shoe I would always look out for from a business point of view would be the Dublin, Stockholm and Brussels designs,” says Wyatt.

One thing that becomes quickly clear when researching the City Series is how occluded its history is. In itself, this is not so unusual – many fashion and athletic brands have patchy archives and myths build up around them based on half-memories, blurred photographs and second-hand reports. But in this case, the diffuse nature of the range and adidas’ historic habit of using localised and semi-autonomous production centres makes the problem especially acute.

Adidas City Series Dublin, 1980. Photograph courtesy of adidasArchive/Studio Waldeck

Mr Peter O’Toole is an English illustrator who has worked extensively with adidas (even co-producing a signature shoe, the Quotoole, alongside esteemed German adidas collector Quote in 2014), and who produced a graphic print in 2011 cataloguing and displaying the entire City Series – and featuring a staggering 98 different shoes. Talking about the scale of the project quickly gives a glimpse of the complexity of the series’ history.

“There are variants to certain models, like the Hamburg with the light and dark soles, the Wien Mark II which had a different toe box to the original. The Bern Mark II had a completely different sole unit. Also you had shoes that were manufactured in different countries and had the same name as existing City models but were completely different,” O’Toole says.

Further complicating things, a later series of City shoes were built around the identities of North American cities, utilising a more classic running-shoe profile. The City Series now spanned not just cities and continents, but entire sports and styles.

But, in the big picture sense, the City Series shines. When considered in its totality, the line’s cohesive identity reveals itself more easily than when fixating on the specifics of individual models: most model’s prioritise quality of materials over visible technical flourishes, pair colourways and stripe tones with a graphic designer’s exacting sensibility and have detailed finishes which reward close examination (for example, the shaggy suede of the Hamburg or the textured sole of the London).

While the shoes often feel more like cousins than direct descendants of one another, the shared metropolitan, modernist aesthetic distinguishes them and partly explains why they’ve remained a constant building block of outfits for men who like understated, but carefully considered style.

Adidas City Series Hamburg, 1982. Photograph courtesy of adidasArchive/Studio Waldeck

The City Series’ ongoing relevance has been ensured by a particularly astute reissue programme over the past decade or so. “I remember, in around 2008, there was a resurgence in interest in the City Series with the younger generation,” says O’Toole. “For the first time, I saw reissue trainers go for more money than the original models and I knew something had changed.”

Wyatt saw similar shifts taking place from the early 2000s onwards: “The City Series reissues from then became very popular with football lads who were not old enough to be around in the early 1980s,” he says.

Rather than just a straight reissue, some City shoes have also been reinterpreted: as part of the Spezial series, with the original Montreal rebirthed as the Hochelaga; a Mundial and Size collaboration in 2020 produced the Liverpool, Córdoba and Havana; a Tricolour-coloured Paris appeared in limited numbers in 2012 to mark a store opening in the French capital, before it reappeared in the summer of 2020 more widely.

For City Series enthusiasts, this seems to be a golden period. Mac points to a marked increase in the quality of reissues and remodels currently available. “I think that City models have never been made so good,” he claims. “If you look at Wien, Amsterdam, Napoli, Torino and even the niche Frankfurt, they were all strong reissues. Since the start of Spezial in 2014, City Series have been stepped up.”

But as much as this build quality has elevated the shoe’s standing – and despite the multifarious colourways, finishes, sole variations and hidden details – a large part of the City Series’ longevity comes down to its unflashy nature. “It’s the simple, iconic design,” says O’Toole.

“I think the answer is its simplicity,” says Mac. “It’s not a technical shoe and this has always been reflected in the price point, its clashing colours, its gum sole and the ability to dress from the feet up. I know many, many lads who have dressed for the day around whatever pair of City trainers they’ve picked out.”

In a market swamped by novelty, hype and innovation, this in itself becomes a unique selling point. As Mac concludes: “They can be matched with anything.” And long may they continue to be so.