THE JOURNAL

Sir Ranulph Fiennes in full cold weather outfit during his unsupported expedition to the Antarctic, circa 1992. Photograph by Sir Ranulph Fiennes/Royal Geographic Society/Getty Images

Why you will never be as tough as “the world’s greatest living explorer”.

Less known than his many achievements as “the world’s greatest living explorer”, Sir Ranulph Fiennes was once invited to audition for the role of James Bond. After Mr George Lazenby’s single abortive outing as the spy in 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, producer Mr Cubby Broccoli, according to the voice on the phone, was looking for “an English gentleman who really does these things”. “What things?” asked Sir Ranulph. “Shoot rapids, climb drainpipes, parachute, kill people, you know…” Alas, he was adjudged, in his own harsh words, “too young, most un-Bond-like and facially more like a farmhand”. (His third cousin Mr Ralph Fiennes would later play M opposite Mr Daniel Craig’s 007.)

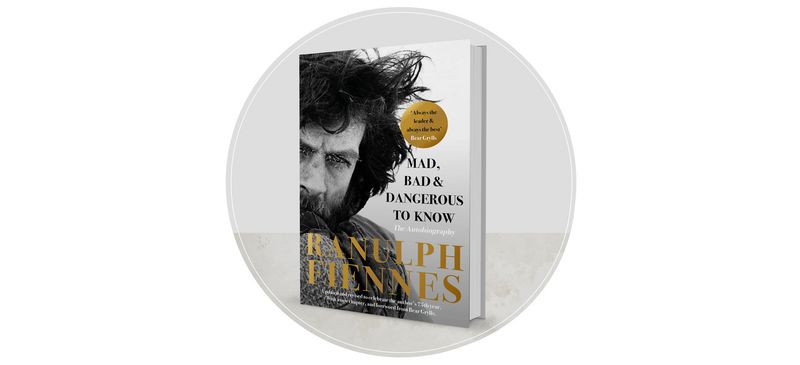

Sir Ranulph really did those things, though, as attested by his astonishing autobiography Mad, Bad And Dangerous To Know, which raises more eyebrows than Sir Roger Moore did. Originally published in 2007, the book has been updated to reflect the fact that Sir Ranulph turns 75 on 7 March this year and is still doing things, including running and planning expeditions. (Record guardian Guinness dubbed him “the world’s greatest living explorer” in 1984.) Wonderfully matter-of-fact about the hardships he’s endured, the feats he’s accomplished and the millions he’s raised for worthy causes, he’s made of stiff-upper-lipped stuff, as these chapters from his must-read life story demonstrate.

He passed SAS selection, becoming the youngest captain in the army. Shortly after, an old Etonian friend enlisted him to protest a dam built over a trout stream in a Wiltshire village by 20th Century Fox for the filming of 1967’s Doctor Dolittle, using explosives left over from Sir Ranulph’s demolition training. A journalist tapped to publicise the stunt shopped them to a tabloid, which in turn informed the police, and Sir Ranulph was booted out of the special forces. His future father-in-law thus bestowed the “mad, bad” title given to Lord Byron upon his daughter’s suitor (of whom he was not approving).

Together with Mr Charles Burton, Sir Ranulph became the first person to circumnavigate the globe via both poles – suggested by his wife and initially dismissed by him as impossible, before he eventually and grudgingly acceded. (Ah, marriage.) After 14 months, over 100,000 miles and one shot polar bear, Sir Ranulph and Mr Burton returned to Greenwich, London, and received the Polar Medal. Mr Burton later floated the idea of a first unsupported crossing of the Antarctic continent on foot, which Sir Ranulph also deemed undoable at the outset, but nevertheless achieved with Dr Mike Stroud.

With Dr Stroud, “Ran” ran a record-breaking seven marathons in six continents (Antarctica was discounted due to weather conditions, so he ran in the Falkland Islands instead, and thereby South America twice) in seven days – a scarcely credible coup even before you consider that he was 59, or that he had suffered a heart attack and undergone emergency bypass surgery four months previously. He’d signed up for the challenge before his cardiac event and didn’t consider cancelling. None of his surgeon’s previous patients had asked if they could run a marathon after (Sir Ranulph neglected to mention that he was intending to run seven – two in the same 24 hours because of time difference), but the doc figured he’d be OK if he didn’t push it.

Perhaps most infamously, he cut off the ends of the fingers and thumb of one hand after they were frostbitten beyond repair. A month before surgery to remove the dead tissue, and prompted by a suggestion from his wife that he’d become irritable from the pain, he “decided to take the matter into my own hands”. He tried to prune his little finger with a pair of secateurs, but it hurt too much, so he purchased a set of fretsaw blades from the village shop, put his hand in a vice and DIY amputated the frosted tips over the course of a week. He still keeps them in a drawer of his desk, in a mouse-proof tin.

He summited Everest at the third attempt and the age of 65, having previously been thwarted by chest pains and bad weather. He’d hoped that climbing the world’s tallest mountain would force him to face and finally conquer his lifelong fear of heights, but was disappointed by the lack of sheer drops. So, with five semi-amputated digits, he tackled the notorious north face of the Eiger, nicknamed Mordwand or “Murder Wall” (a grim pun on its German name of Nordwand, or North Wall), which Austrian alpinist Mr Heinrich Harrer described as “an irrefutable touchstone of a climber’s stature as a mountaineer and a man”.

Choose your own adventure

The people featured in this story are not associated with and do not endorse

MR PORTER or the products shown