THE JOURNAL

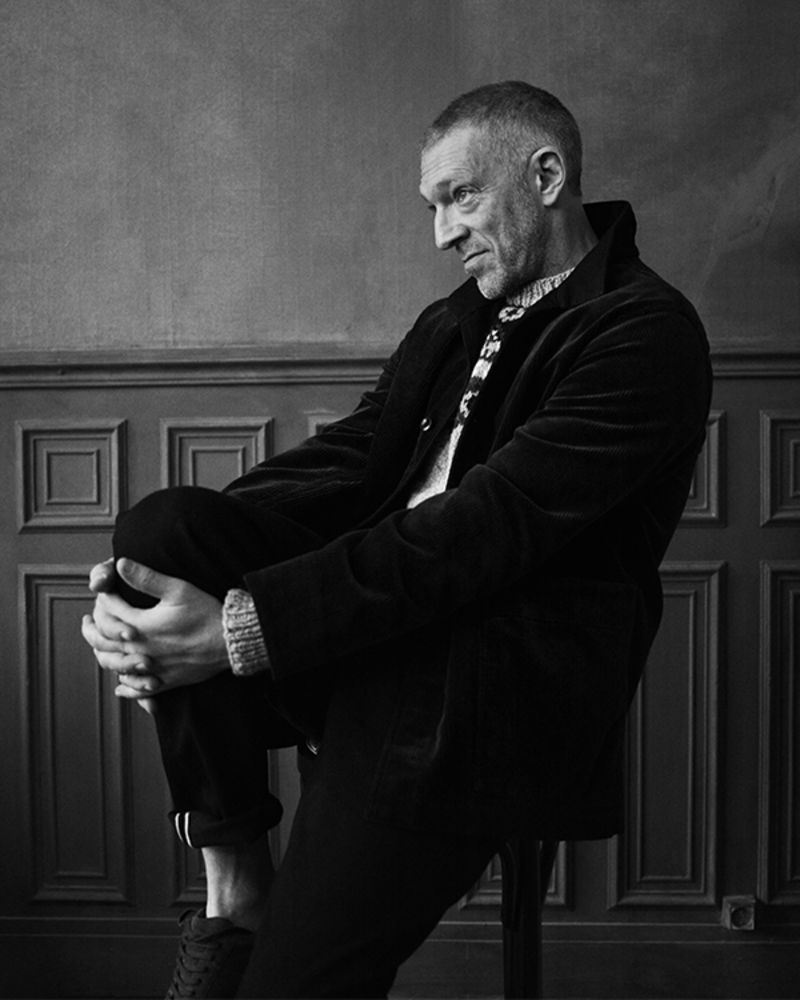

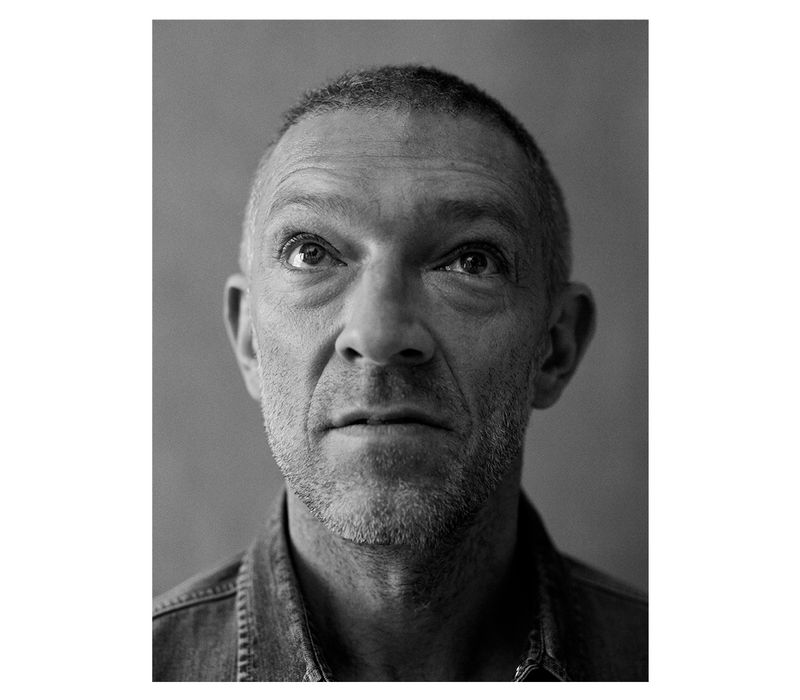

When it comes to French artists, it sometimes feels as though people only care about one thing: how French are they? How much sighing, how much shrugging, how many Gauloises do they smoke? In Mr Vincent Cassel’s case, the answer is clear as day. The 53-year-old movie star, whose film credits include the glossy Ocean’s Twelve and the gritty La Haine, is “soooo French”, he admits with a chuckle. “I’m as French as you can get.” He’s so Gallic, he even appeared in one of those mythic Renault Clio adverts of the 1990s as one of Nicole’s many boyfriends.

“I appeared for a second and a half,” says Mr Cassel when we speak, mostly in French, but with smidgeons of English, which he speaks fluently. The advert aired 25 years ago and he is quite tickled at the memory. “There’s no shame,” he says. “I’m very happy with it.”

Mr Cassel is not only classically French, he is also a classic movie star and they are few and far between these days. Consider his CV, which is stacked with arty, challenging roles for filmmakers such as Messrs Darren Aronofsky, David Cronenberg and Steven Soderbergh. Consider his private life – a marriage to Italian screen bomba Ms Monica Bellucci, which made them one of the movies’ most handsome modern couples, followed by a surprise recent second one to model Ms Tina Kunakey, who, at 22, is some 30 years Mr Cassel’s junior. (They’ve just welcomed a baby daughter, Mr Cassel’s third child. He has two with Ms Bellucci.) And consider the all-round attitude, which seems to sit somewhere between no f***s given and a regal courtesy. Par exemple, I was supposed to meet Mr Cassel in Paris after his MR PORTER photoshoot, but, when it finished early, he left and that was that. However, when we speak on the phone a day later, I get all his attention, a rapid-fire sequence of unflinching answers delivered with humour and, sometimes, charm. Basically, when he’s on, he’s on. When he’s not, he’s not. And it’s always been like this, apparently.

“I thought about this the other day,” he says. “I was on my scooter, going from one rendezvous to another, and I thought, I spend my days mostly as I did when I was 17. I get up in the morning and I run, I run, I run, I have loads of energy, I talk very fast, I think of 12,000 things at a time and then in the evenings I get home and I’m exhausted. Basically, it’s either cold or really hot. But lukewarm? I just can’t do it.”

Which brings us to Mr Cassel’s latest movie, Underwater. The film, which co-stars Ms Kristen Stewart, is a delirious aquatic action nightmare. They play well-meaning researchers who become trapped in an underwater rig in which they have been exploring the ocean’s beds. When the rig implodes, they must face assorted sea monsters and their own fear. Mr Cassel is typically succinct in summing up its appeal. “Adventure. Voilà.” The adventure of doing sci-fi, which he’d never done before, the adventure of working with a “modern young cultural icon” such as Ms Stewart and the adventure of “for the first time being offered a Hollywood film where I wasn’t the so-called baddie, but was instead a paternal, even reassuring figure”.

“You know, people say Parisians are snobs, always annoyed, always moaning about everything. It’s true. I am, too”

Mr Cassel has hit the nail on the head. Whether it’s in the Ocean’s franchise (he appeared in Twelve and Thirteen), in Jason Bourne or even in Mr Aronofsky’s Black Swan, where he helped make ballet look terrifying, he is often asked to turn up and look mean. He isn’t unduly upset by it. “We’re always a little bit the victims of what we represent, of the face we have, basically,” he shrugs. “I always tried to turn whatever it was that people gave me into something to my own advantage. When I’m asked to play a baddie, on paper that’s one thing. And then I go and try and do another.” Those louche roles are generally more to his taste, anyway. “What interests me is when you show what people don’t usually want to see in themselves,” he says. “You know, when you’re in a cinema and you see an actor do something and it speaks to you about something you want to hide.”

Mr Cassel has always felt like an “outsider” in France, even though he has lived there for most of his life, except for a few years’ residency in Brazil with Ms Bellucci before they divorced in 2013. This may seem surprising considering his level of success and his background. He is the son of a very famous actor in France, Mr Jean-Pierre Cassel. The two have had very different trajectories, however. Mr Cassel senior is known for his roles in charming comedies; his son, practically the opposite. Mr Cassel junior has rarely had anything positive to say about his childhood, which was apparently spent languishing in a sequence of unpleasant schools. Even a year spent in London, at the age of 11, when his father was acting in the West End, gets a pretty damning review. “A place where it’s always a bit cold, where you don’t eat very well, but where there were very nice chocolates.” Today, he freely admits that even when he followed in his father’s footsteps, he was trying to wipe them out, too.

“As they say in psychoanalysis, you have to kill your father,” he says. “So, everything that represented my father’s generation, for me, was totally excluded from my choices. I always made a point, right up until his death, to make films with people my own age. It was my generation before all else.”

The most obvious example of this is La Haine, which gave Mr Cassel his breakout role in 1995. The film, a commercial and critical hit, was a tough portrait of life in France’s harshest banlieues. You couldn’t get a clearer “up yours” to the cosy certainties of a previous era of cinéma français. “It was a way for me to integrate myself into my generation and to inscribe myself on it, too,” says Mr Cassel. Does he think he succeeded? “Yes!” A big, booming laugh.

Over the next quarter century, a solid stream of work in France and abroad followed, although Mr Cassel is at pains to point out that he has not made that many Tinseltown movies. “I think if I just made Hollywood films, I’d have stopped this job a long time ago,” he says. “Non, non, non!” He is prouder of his work in, for example, Mr Gaspar Noé’s Irréversible, one of the many films he made with Ms Bellucci when they were together. The film, which features a notorious long rape scene, was draining on every level. “I came out of it on my hands and knees,” he says. “But, you know, it was still a pleasure.” Is it more satisfying for having made that effort, then? He tuts.

“Life is hard enough as it is. If you can have fun doing things, that’s what I try to do”

“Oh, you know, that Judaeo-Christian complex where you need to suffer to do something good – I don’t believe in that,” he says. “It’s something I cured myself of a while back. I tell myself life is hard enough as it is. I prefer to suffer truly when there’s no other way. If you can have fun doing things, that’s what I try to do.”

This is Mr Cassel’s attitude towards Christmas, too. However much I prod him about the joys of the festive season, especially with a new baby at home (Amazonie, his child with Ms Kunakey, was born in April), he doesn’t take the bait. “The tree, the presents, the midnight mass – it makes no sense,” he says. He’ll spend Christmas in Brazil, where he still has a home, but he is not a grouch when it comes to family. His two daughters with Ms Bellucci are 15 and nine and, he says, “my career has never come before my kids”. Giving your children your time is the most important type of love, he insists. “Honestly, I don’t really obey any rules as to how I should bring up my kids. I really do it according to my personal conscience, according to the moment and I’m sure I’ve made some errors.” He often returns to that Mr Oscar Wilde quote, “Children begin by loving their parents; as they grow older, they judge them; sometimes they forgive them.”

Mr Cassel’s frankness is nearly always tempered by self-awareness and a dry wit. “You know, people say Parisians are snobs, always annoyed, always moaning about everything,” he says. “It’s true. I am, too.” And for all his talk of “killing” his father, he says they had a good relationship until his death in 2007. Mr Cassel feels his influence enormously now and says he gave him the best advice: “there are no rules”.

Then there’s getting married again, which he did last year. Mr Cassel hadn’t expected it after his divorce, but “it’s a wonderful thing. Once you’ve said, ‘I love you,’ sincerely once in your life, it’s hard to say it again because you think it might not have the same value. But actually, possibly, you find yourself saying it again and you believe it.”

That, and presumably he’s a different person now. “Ah, mais non! I don’t think people change,” he says. “I think that you learn to accept yourself, but I don’t think you change.” A Gallic shrug is almost audible down the line. “Definitely. Not completely, yet. But let’s just say there are fewer grey areas.”

Underwater is out on 10 January (US); 7 February (UK)