THE JOURNAL

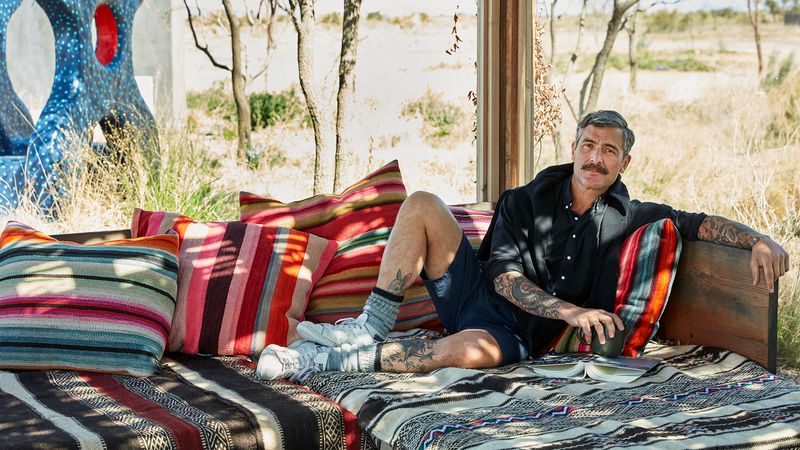

“I’m so energised by the remoteness,” Mr Douglas Friedman says. “I love the desert. I love to drive. Out here, it’s my fantasy”

The first time Mr Douglas Friedman came to Marfa, Texas, it was under less than ideal circumstances. The newest member of the MR PORTER Style Council was there on a romantic getaway, but the chemistry was fizzling. The July weather was scorching, the air humid. The days he dropped in, Monday and Tuesday, are when almost everything in the sleepy, high desert settlement is closed.

“All things considered, it wasn’t great,” Friedman says. Despite all that, the trip touched something deep within him: a love of adventure, nature, and wide-open spaces, and the romance and mystique of the desert. “I left consumed with the idea of this little town,” he says.

“Donald Judd figured it out, and I’ve figured something out here,” Mr Friedman says

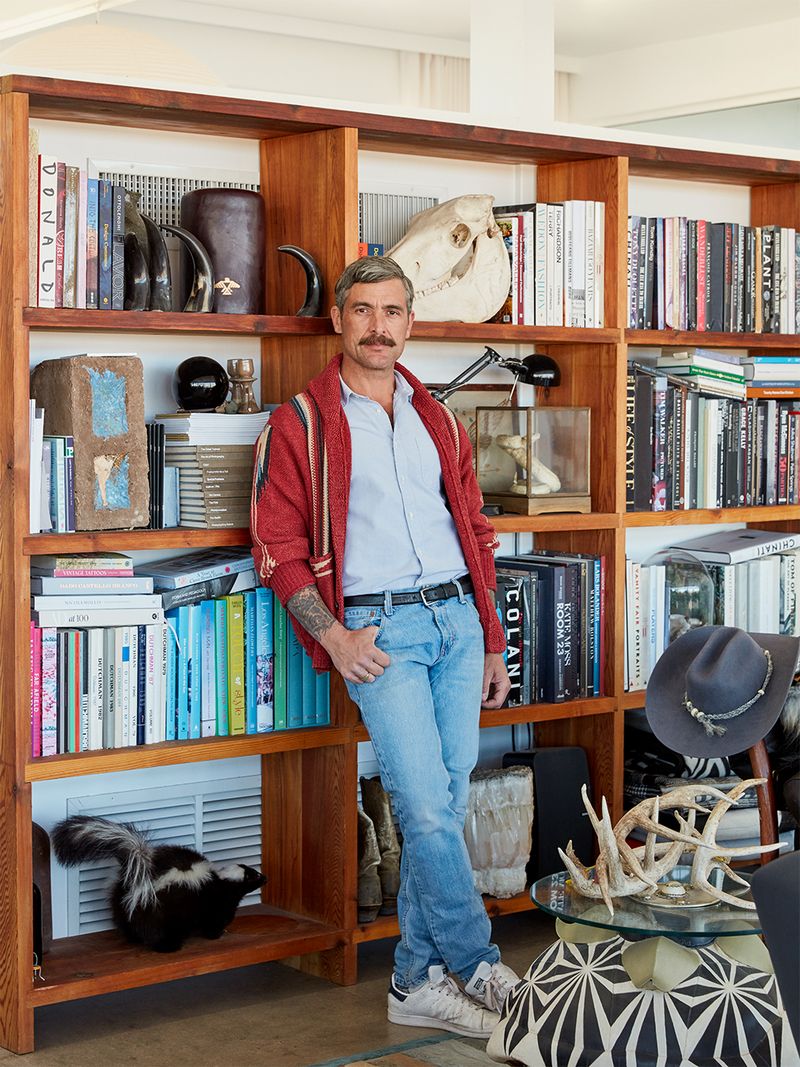

“Can we not call it eclectic?” Mr Friedman says of his decor. His preferred phrase is “wabi-sabi funk”

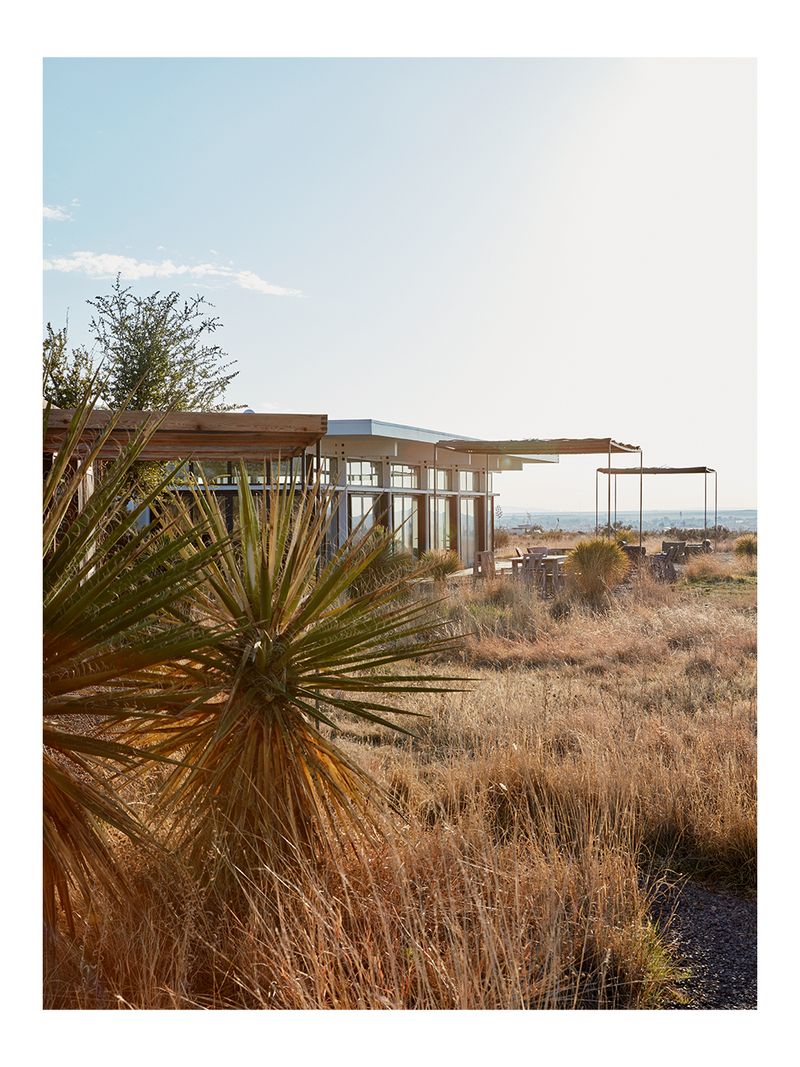

The house is built from insulated panels (SIPs), with all wiring hidden from view

This might sound surprising coming from Friedman. The stylish, mustachioed and heavily tattooed fashion, interiors and travel photographer is very much the modern archetype of an urbane man about town. He’s annoyingly handsome – like a Tom of Finland illustration come to life. He has a coterie of fabulous and creative friends while his job brings him elbow-to-elbow with New York’s elite power brokers.

Still, when Friedman returned home, suddenly all of his friends were abuzz about Marfa: at a dinner, the domestic goddess Ms Martha Stewart recalled featuring the town in a 1996 issue of her magazine; Mr Trey Laird, the influential art director, was building a house there; and Mr Stefano Tonchi, the art-savvy magazine editor, sang its praises. So, when Laird and his wife Jenny invited him to return, Friedman jumped at the opportunity and convinced his pal, Ms Ally Hilfiger (artist, author, and, yes, heiress to the Tommy Hilfiger empire), to tag along. Together they rented a convertible and donned cowboy boots and ponchos, and it was on that fateful trip that Friedman decided to buy land there.

“I was swept up by it,” he says. Marfa may be two flights and a three-hour drive from New York, but the photographer goes as often as work allows: “I’m so energised by the remoteness. I love the desert. I love to drive. Out here, it’s my fantasy.”

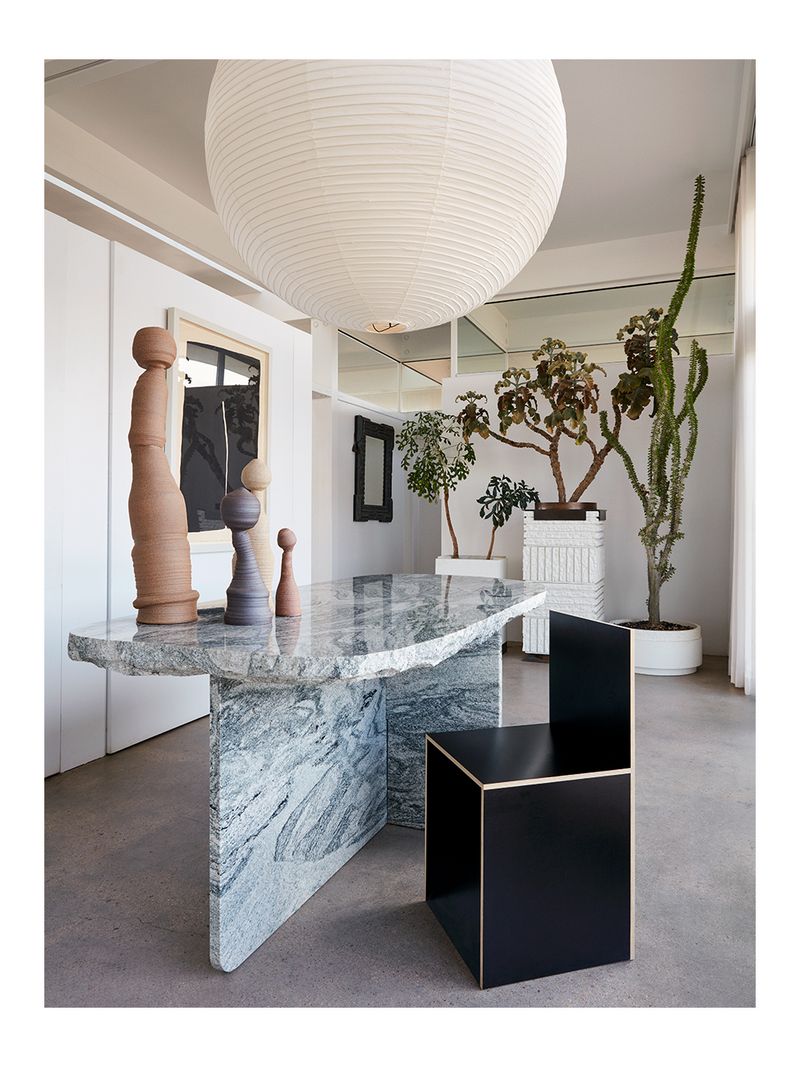

“Those are finds, real finds, and I’m proud of those,” Mr Friedman says of his Donald Judd chair, Noguchi lantern and raw-edge black travertine table, which he recovered himself

The minimalist architectural imprint provides a backdrop for Mr Friedman’s more expressive impulses, with treasures accrued during his travels placed alongside pieces found locally

Friedman is part of a long line of creatives who have been drawn to this small, seductive village. Originally founded as a railroad water stop in the 1880s, the town has gained an outsize presence for its diminutive size. First when the Mr James Dean and Ms Elizabeth Taylor epic Giant was filmed there in the 1950s and two decades later when it beckoned a wave of high-profile artists from New York, most notably Mr Donald Judd, who founded the contemporary art museum the Chinati Foundation there. Ever since, it has lured urban creatives with a case of wanderlust and those looking to lose themselves in the Texas plains. Oh, and of course there’s the legend of the Marfa lights, the otherworldly, mysterious luminescence that dances across the empty vistas at night.

Friedman recalls the first time he saw this humble plot of land, just three miles outside of town. Ms Mary Farley, his real estate agent and a local legend (the ex-wife to artist Mr Matthew Barney, Farley had a role in the 2012 Mr Larry Clark film Marfa Girl), had saved it for last.

“She played that trick with me where she showed me, like, a hundred things that she knew weren’t right,” he says. “And then, at the end of the day, when that light is raking across the landscape, and it’s so seductive, she was like, ‘You know, I may know of something that’s not on the market yet…’”

“I wanted the space to reflect, I guess, my brain in some weird way. And I think it does”

It was there, looking at those achingly beautiful vistas that stretch over 10 acres, that Friedman began to consider his dream home. His fantasy was an Airstream and a couple of chairs, but then he got more ambitious about it. And so Friedman began to build what would become a sleek white box covered with vast, angular planes of glass.

The clean, airy facade is inspired in part by Judd’s legacy of stark and functional artworks, but also the practical requirements of erecting a home from scratch in such inhospitable environs. The house is essentially a modified jigsaw puzzle of structural insulated panels (known as SIPs) that were shipped to the desert (sometimes driven in by Friedman himself) and built on-site by a local contractor, Mr Billy Maginot.

That streamlined energy extends to the interior construction, where any mechanical systems – wiring, vents and the like – are hidden from view. Even in the matte black kitchen, a modular design by the Danish design firm Vipp, conceals the refrigerator and dishwasher.

The shaded lounging couch covered with bright Bolivian textiles, with artwork by Mr Brett Douglas Hunter (behind)

The house is made for indoor-outdoor living, best evidenced by the oversized al fresco dining table and a shaded lounging couch covered in festive Bolivian textiles in vibrant hues, offset by joyful sculptures from the artist Mr Brett Douglas Hunter. There’s an elegant pool and hot tub, by ModPools, which arrived on a flatbed truck from Canada and was plopped into a hole in the ground by crane.

And while there’s an effortlessness and serenity to the end result, it belies the heartache and hardship that went to making it. “No one tells you – no one warns you – how stupid your ideas are,” Friedman says with a laugh.

Well Friedman has made it and then some. While the minimalist exterior and architectural imprint may harken back to Marfa’s artistic lineage, the decor is bustling with personality and Lone Star charm. In fact, the whole venture bristles with a tension derived from the push and pull between Friedman’s desire for simplicity and his more, shall we say, expressive impulses.

The house is made for indoor-outdoor living

“No one warns you how stupid your ideas are,” Mr Friedman says of building the house

In addition to help from local purveyors of home goods, Garza Marfa, Friedman rounded out the home’s decor with special treasures that have accrued during his travels and placed together in a harmonious discord.

“Can we not call it eclectic?” he bemoans. His preferred phrase is “wabi-sabi funk”.

Travelling around Texas has yielded its own trove, such as a rugged Don S Shoemaker chair he has in his bedroom, which he bought at a steep discount, or a black travertine table he came across when it was covered in mould and dirt, which he then revived with a trusty power-washer. “Those are finds, real finds, and I’m proud of those,” he says. He even got his Donald Judd chair, finally, which sits under a Noguchi lantern and next to a raw-edge stone table.

Friedman approaches his house less as a fixed tableaux and more of a living organism that’s always in flux, allowing him the flexibility to shuffle pieces out and others in. But the real magic of what he has achieved is in creating a home that is, in and of itself, a feast for the eyes, but also spotlights the remarkable energy of Marfa.

The pool and hot tub were brought from Canada on a flatbed truck and installed with a crane

“You’re almost a mile high, and it’s ringed with mountains,” he says of the locale. “But it used to be the bottom of the ocean. So there’s fossils and things. There’s the Marfa lights. Marfa was always a place where people gravitated toward. It’s always been a thing. Donald Judd figured it out, and I’ve figured something out here.”

What Friedman’s figured out, exactly, is hard to put into words. In the decade he’s owned this place, it’s become an obsession of sorts: “Like, every blade of grass, every tree, every nail, every pebble. I thought about it, I considered it. I nurtured it.”

He’s had to learn to live with losing things, like the jasmine he loved that was killed in a recent storm. But that’s life in these conditions. “It’s not easy at all to live here,” he says. “It’s physically and emotionally hard. But it’s worth it. I don’t know if I could be anywhere else right now.”