THE JOURNAL

Sculpted from bronze, this limited-edition, automatic 72-hour power reserve diving watch is one for the ages.

Watchmakers have long experimented with the latest materials – titanium, ceramic, even nano-tube carbon have made their way onto our wrists. Steel is the functional mainstay, while gold symbolises wealth, or retirement. But it’s taken almost half a millenium to get around to trying bronze, despite its innate attractiveness.

In its day, bronze was the high-tech material; tin was mined and smelted, then added to molten copper to create bronze alloy, which then had to be shaped in a mould. It literally changed the landscape and, by turns, global society, allowing for the transition from stone weaponry to metal, as well as the armour to block said weaponry. It also made for new art forms, upscale homeware and jewellery – such as gorgets and torque, metal collars worn around the neck – considered so precious that they often ended up as grave goods. This jewellery might not have ticked, but it appreciated the potential and appeal of bronze nonetheless.

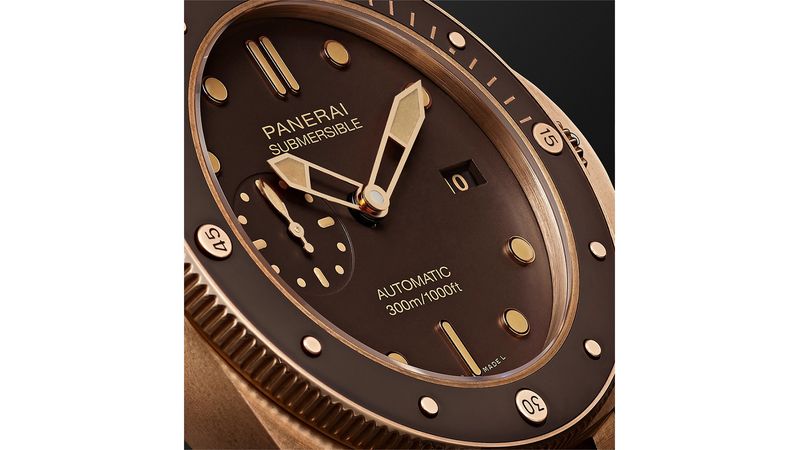

Jump forward many centuries and Italian watch brand Officine Panerai – a company known primarily for the macho functionality of its rugged timepieces – now launches its Submersible Bronzo. This automatic, 72-hour power reserve diving watch, currently available in limited numbers from MR PORTER and Panerai boutiques, steps up the tech by using a brown ceramic dial with either a leather or rubber strap, but its exterior is otherwise 161 grams of heavy metal. It’s ideal for getting you down to its operating depth of 300m somewhat faster than planned.

Panerai has something of a history in bronze. The Bronzo was first released in 2011 – a 1950 three-days reserve, olive-dialled model – and created a stir not just for being the first sports watch to feature a chunky 47mm case entirely made out of bronze, but also for offering that bronze with a just-so time-weathered effect. No wonder all 1,000 pieces of that limited edition were rapidly snapped by devoted fans, the Paneristi, in particular, or that Panerai sought to build on that success two years later with another Bronzo, this time with a power-reserve indicator, and then in 2017 with a blue-dialled version. A benchmark of their special desirability, all command significant premiums on the secondary market.

Of course, Panerai is not the only maker to have embraced this lustrous metal over the past few years. But most have entered the bronze age only tentatively, then been somewhat surprised by the positive response. In part, the reluctance stems from the inevitable patination – brass, for example, needs frequent polishing to wipe back the murkiness caused by exposure to temperature fluctuations, friction, humidity and even the air (or at least the oxygen in it). This cuts against the long-held association between prestige and all things gleaming.

Maybe this is why it took a while for the legendary watch designer Mr Gérald Genta to propose the first production watch in bronze, back in 1988, with the Gefica Safari. And perhaps it was a comment on its inevitable limited commerciality that, unlike in 2007 when the model was re-issued, it was only available to his friends. Yet Mr Genta’s reasoning for selecting bronze wasn’t just aesthetic. He wanted a watch to wear on a safari trip to East Africa: unlike steel, bronze is a poor reflector of light, thus would not give the hunter’s presence away to his prey.

In a Panerai watch, the choice of bronze might well stop the Bronzo’s wearer becoming prey to a passing great white. Indeed, back in 1985, the company ran with this idea by producing a prototype specialist piece in bronze for the Italian navy. Diving watches, after all, are what Panerai has always really been about – and its later return to bronze for commercial models was with good reason.

Sure, for most wearers, it’s undoubtedly the distinctive look of bronze that is its first appeal. Yet both varieties of bronze – copper mixed with tin, and the cheaper, more modern version that sees copper mixed with the more plentiful aluminium – are stable and strong; not as chemically inert or hard as steel, but not far off. Bronze is closer to plastic than steel, making it easier to work and more able to carry fine details. It’s also anti-magnetic. What’s more – and this is where the choice for a diving watch makes most sense – it’s a marine-grade alloy, which is to say that it can be used in salt water, indefinitely, with almost no signs of corrosion. Really, all diving watches should ideally be made of bronze.

That’s why, from the weight belt and glove seals to, most distinctively, the helmet, the equipment worn by deep-sea divers was, historically, made of bronze’s more malleable cousin brass – at least until the 1960s. It’s why many ship instruments, from bells to porthole pictures and bridge compasses to telescopes, were made of the same material, too. This fact gives contemporary watches in bronze something of a retro-futuristic, steampunk feel.

Of course, there’s bronze and there’s bronze. Top-flight makers the likes of Panerai don’t just select this earliest of civilisation-making metals and leave it at that. It is micro-sandblasted, bead-blasted, brushed and even undergoes deliberate oxidation to get that particular finish and tone. Through this, bronze attains the status of precious metal that it once had.