THE JOURNAL

Jay-Z and Mr François-Henry Bennahmias at the launch of the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore Jay-Z 10th Anniversary Limited Edition, Four Seasons Hotel in New York, 19 April 2005. Photograph by Mr Kevin Mazur/Getty Images

“We don’t give watches away,” Audemars Piguet’s ex-CEO Mr François-Henry Bennahmias once declared, back in the mid-2000s. What he meant by that was that although the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore was the hottest property in watchmaking, he had got it on the wrists of actors and musicians without spending a cent on “brand ambassadors” or pushing free watches in their direction.

The Offshore was a phenomenon – the “it-watch” of its time. And it was notable because AP had become the first watch brand to break into the underground of street culture, hip-hop celebrity, earning straight-backed Switzerland a genuine cool factor.

Partly it happened because Audemars’ Royal Oak was a 1970s sleeper of bling-bling, with an octagon of broad facets ripe for after-market, iced-out diamond “bust-downs”. But mostly because Bennahmias was mixing with the edgiest, brand-canniest of the West and East Coast scenes in his formative years running AP North America. He sowed the seeds for the “hype watches” of the 2020s. However, Bennahmias didn’t invent the it-watch, he merely turbocharged it. To know where the idea of a watch as must-have status symbol came from, you have to go back to the 1980s.

“One of the most ‘wow’ moments for watches in history was that first Swatch collaboration in 1986 with Keith Haring, when the artist and his Pop Shop on Lafayette Street in New York were still breathing,” recalls zeitgeist commentator, photographer and dyed-in-the-wool fashion scenester Mr Mark C O’Flaherty.

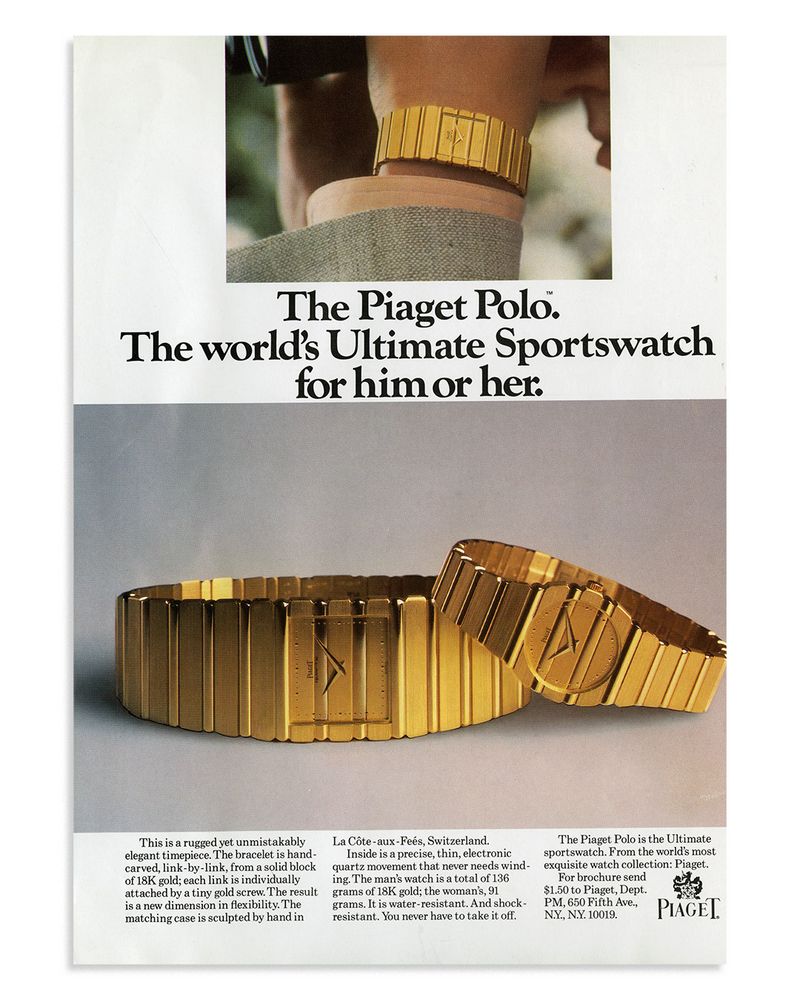

Piaget Polo advertisement from 1982. Image courtesy of Piaget

“The Swatch collab with Vivienne Westwood was just as striking,” O’Flaherty says. “In 1992, she was still counterculture, so it felt shocking and brilliant. I had a Putti Pop Swatch, which I left at a party and never saw again – the host was a drug dealer, he was arrested and everything in his flat was confiscated. The watch went the way of many things sharing roots in punk – an apposite fate.

“Nonetheless, both these collaborations made the kind of people who didn’t buy watches want to buy a watch,” O’Flaherty says. “They worked because they took imagery that had a talismanic as well as cool quality to it, and stamped it on a timepiece.”

The plastic-fantastic Swatch was indeed watch as fashion, but also a desperate lifeline for the Swiss industry facing ruin at the hands of affordable, quartz-based watches. Since then, every generation of contemporary “pop” has had its own horological poster-child (or two). But it wasn’t confined to fun, accessible designs such as the Swatch. In fact, it-watches have tended to be extremely exclusive, and that began with the way that established luxury brands reacted to the arrival of quartz watches.

“I would go back to the 1970s when the quartz crisis was still wreaking havoc across the industry,” says Mr Alexander Barter, once a director for Sotheby’s Watches and now co-owner of vintage boutique Black Bough and co-author of coffee-table books, such as last year’s lavish 500 Years, 100 Watches. “Despite the extent of new-fangled electronics ravaging the Swiss craft, some brands could see that that wouldn’t always be the case. There was no romance in circuitry or cheap disposability, so they started to trade on the very defiance of that.

“Just look at Blancpain’s ‘we will never make a quartz watch’ campaign,” Barter says. “It was getting pretty obvious that to sell to the burgeoning yuppy set, it had to be mechanical, lavish. And that in my opinion stems from Piaget’s all-gold and literally ‘groovy’ Polo of 1979 – the epitome of Palm Beach glamour.”

“Franck Muller almost singlehandedly reestablished haute horlogerie as an innovative thing – but also a fashionable thing”

Barter is referencing a febrile pop-cultural moment for horology: snaps of Switzerland’s OG watchmaking playboy, Mr Yves Piaget, hanging out with Ms Ursula Andress between chukkas, duly rocking a Polo in gold. (The model has been reissued in its 45th-anniversary year.) Ironically, the original Polo did use a quartz movement, albeit a bespoke, Swiss-made one developed by Piaget – but it was all about what it stood for, not what was inside.

Mr Steve Martin wore a Polo in Planes, Trains And Automobiles (1987), famously trading it for a night’s stay at a motel (while Mr John Candy’s Casio couldn’t). The same year, Cartier’s own flex of 1980s “disco-luxe” wrist candy earned another iconic chunk of real estate on the big screen: a gold Santos keeping time on the markets for Michael Douglas’ Wall Street wolf-turned-reptile, Gordon Gekko. These unapologetically decadent watches were a literal wristband to enter society’s elite.

“By 1989, fine Swiss watches had become a status symbol and, literally, a hot commodity,” Barter says. “And then came the rise of the independent watchmaking scene. Something that brought unheard-of clout – to the watchmakers themselves, but also the wearers, who discovered a new way of showing off their knowledge and taste.”

Yves Piaget might have been the OG watch-brand playboy, but the resurgence of watchmaking in the 1990s coincided with the true rise of celebrity culture, the always-on sensationalism of rolling news, MTV and gossip magazines. If you were in the right place at the right time, you could acquire playboy status even as the one supplying watches to the rich and famous. Which is exactly what happened.

Mr Michael Douglas in Wall Street, 1987. Photograph by 20th Century Fox/Imago Images

“Once I was told, ‘You have a nose for discovering talents,’ and my feeling about a promising young watchmaker named Franck Muller was good.”

So says Mr Svend Andersen, the Danish-born master who began at Patek Philippe, co-founded l’Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI) then mentored the original rockstar enfant terrible of Swiss watchmaking.

“Franck duly progressed to great things under his own name, almost singlehandedly reestablishing haute horlogerie as an innovative thing,” Andersen says. “But also a fashionable thing.”

Sir Elton John considered Franck to be the “Picasso” of watches, telling the journalist Mr Nick Foulkes in an interview, “Men’s watches were nice but they were boring. Suddenly Franck enabled men to go forward to more daring watches.”

Nothing less than the it-watch of the 1990s, every red-carpet fashionista went crazy for Muller’s flashy, barrel-shaped wrist candy, from Mr Sylvester Stallone to Mr David Beckham to Ms Paris Hilton. Come 1999, when a future holder of the it-watch crown was launched, it’s arguable that Richard Mille had the paparazzi potency of that unusual “tonneau” case shape firmly in mind.

Ms Jemima Khan and Mr Hugh Grant at a banquet in London, 16 March 2005. Photograph by Mr Anwar Hussein/Getty Images

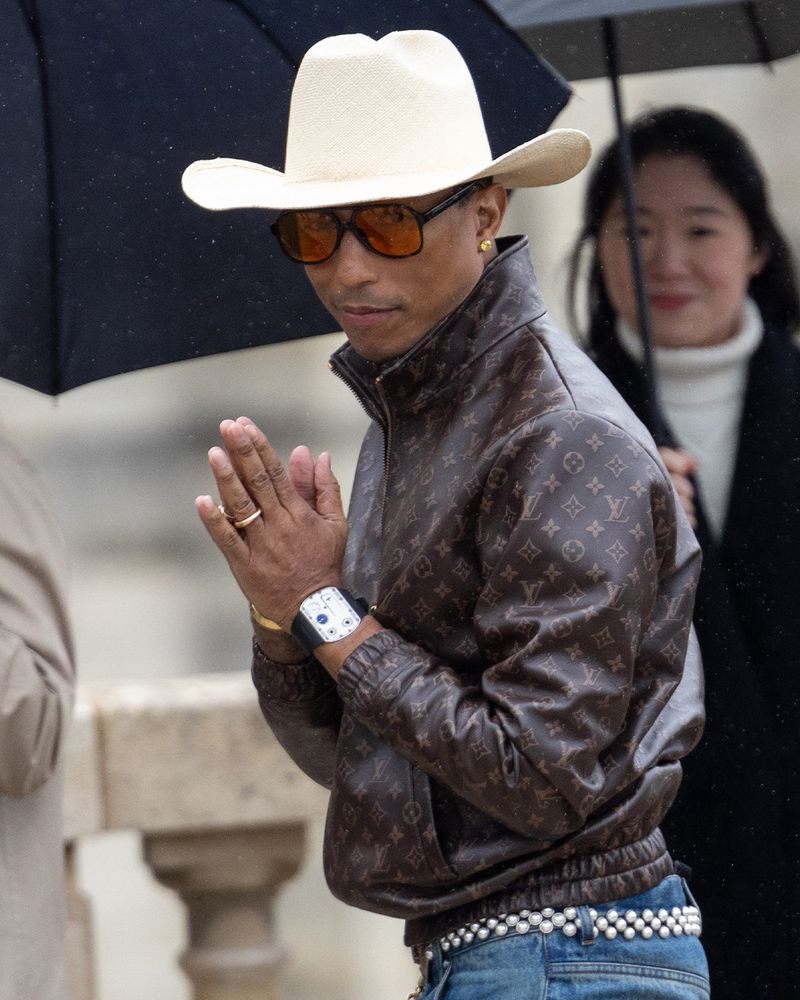

Sure enough, it wasn’t long before Mille was everywhere from the Formula 1 pit lane to the fashion week show – eventually getting namechecked by Mr Pharrell Williams, no less: “She knows the time she sees the Richard Mille, Flat double skeletal tourbillon”.

Dr Rebecca Struthers is a leading academic authority on horology’s cultural arc (see 2023’s Hands Of Time). She cannot help but agree with Barter and O’Flaherty, but adds a measure of wider context.

“I’m a historian of antiquarian horology, so of course I'll always say the idea of an ‘it’ or ‘buzz’ watch has never been new at all,” Struthers says. “The great and the good have always coveted super-expensive one-offs pretty much since their invention. The most famous maybe being Breguet’s watch for Marie-Antoinette, or Henry Graves’ super-complicated Patek pocket watches.

“However, I do agree there’s been a shift in popular culture since the 1980s, and therefore pop’s consumption of watches as a fashionable ‘thing’,” Struthers says. “After Muller and Jacob with the hip-hop and sports celeb hook-ups, one of the biggest shifts I remember was around 2010 when women like Victoria Beckham and Elle Macpherson started wearing sports Rolexes like the Daytona, in steel not only gold. Which triggered a whole wave of women wearing gents watches that they’d self-purchased, not necessarily bought-for by their male other-halves.

“It reminds me of the brief turmoil it caused amid all those old-school blokey watch forums, wracked with doubt over whether their Daytona was still manly enough for them.”

“Having a real relationship with well-regarded boxers, rappers, actors gets you zeitgeist desirability”

While Ms Beckham embraced “the boyfriend watch”, her husband was mostly posing with Mr Jacob Arabo, aka New York’s “Jacob the Jeweller”, the precocious Uzbekistani immigrant, whose bejewelled, multicoloured Five Time Zone was briefly the must-have accessory for any self-respecting international superstar. Unashamedly excessive in size, style and function, the Five Time Zones was worn by Williams, Busta Rhymes, Puff Daddy, Jay-Z, Bono, Ms Naomi Campbell and countless others.

As Ms Malaika Crawford wrote for Hodinkee, Jacob was the man who saw to it that “opulent jewellery no longer belonged exclusively to Elizabeth Taylor or Liberace or Upper East side heiresses.” In 1999, The New York Times dubbed him “the Harry Winston of hip-hop”.

The watch journalist Ms Laura McCreddie-Doak traces the “boyfriend watch” back to 2004, when Ms Jemima Khan single-wristedly kickstarted the trend after being papped wearing a Panerai bought for her by then-beau Mr Hugh Grant.

“Hugh opted for a steel Luminor, but the emergence of Panerai’s more-elegant Due in all shades of gold is – I like to think – not only a chic evolution of the oversized 1990s watch brand, but influenced as a result of their dalliance,” McCreddie-Doak says. “With less said about Jemima likening their break-up to the fact her Panerai had stopped working.”

Mr Pharrell Williams at Paris fashion week, 1 March 2023. Photograph by Mr Arnold Jerocki/Getty Images

By lending VVIP access to in-the-know limited-edition product, AP’s Bennahmias cannily tapped our era’s emerging social media channels. “Bennahmias understood that having a real relationship with well-regarded boxers, rappers, actors,” says LuxeConsult’s Mr Oliver R Müller, who works with Morgan Stanley on its annual watch report. “That gets you real zeitgeist desirability. You’re talking to a generation that doesn’t have a problem reselling watches, where the older generation wouldn’t dream of it.”

Hublot followed suit in the broader sense, but also high-concept brands such as Roger Dubuis (as seen in The Last Dance), Richard Mille (see every grid walk as well as catwalk), even Urwerk (via Mr Robert Downey Jr as Tony Stark and, again, Mr Michael Jordan). All of a sudden rocked on the front row or courtside at the Miami Heat, in an unlikely theatre of A-list connoisseurship.

Patronage of global superstars has always been an essential ingredient for it-watch status, and recent trends suggest the pendulum has swung once more. As we covered in our roundup of 2023’s biggest celebrity watch spots, stars such as Mr Brad Pitt are once again gravitating to the opulence and excess of the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Following huge buzz around the 222, Vacheron Constantin’s 2022 recreation of its 1977 answer to the Royal Oak and Nautilus, Pitt was spotted wearing an original at Wimbledon last year. Meanwhile, Cartier’s “melted” oval Crash, a 1967 cult classic, seems to be everywhere, ever since being seen on Mr Kanye West’s during his interview with Mr David Letterman in 2019.

And after a suitably extravagant press launch for its revival of the Polo in Gstaad this February, Piaget has reminded the world of its claim on the it-watch label. All we need now is for someone to reopen Studio 54.