THE JOURNAL

Mr Harrison Ford at his home in Los Angeles, 1981. Photograph by Ms Nancy Moran/Sygma via Getty Images

One of the many reasons dive watches are so popular – in addition to the outstanding build quality, rich heritage and focused, functional design – is that they tackle one of the most obvious threats to your watch head on. You don’t need a pair of watch experts to tell you you’re in trouble if you get water in your watch, yet watch fans the world over delight in owning watches that are specifically designed to get wet. We relish the over-engineering that keeps water out of our watches, even if they never go deeper than the hotel pool. And it doesn’t hurt that Commander James Bond has famously worn both a Rolex Submariner and an Omega Seamaster.

Water-resistance ratings for watches – not just dive watches, but all watches – are at best confusing and, at worst, downright misleading. We are here to explain what they really mean. It’s a subject fraught with misunderstanding and contradictory advice. We have spoken to experts – watchmakers, divers and physicists – to put together this deep dive (sorry) into water-resistance. The unfortunate truth is that much of the internet is wrong on this subject in some way or other, but we are here to set the record straight. Let’s jump in, shall we?

01. What makes a watch water-resistant?

Ever since WWI, when the practicality and habit of wearing a watch on the wrist became the norm, the exposure of the watch movement to moisture has been a primary concern for all watchmakers.

Various clumsy solutions came about throughout the 1920s, which involved secondary outer cases and hermetically sealed bottletop-style caps on chains. But it was Rolex that blew everyone out of the water, so to speak, with its Oyster solution of 1926. Like a submarine hatch, the crown, bezel and caseback all screwed down tightly onto the central case body – metal to metal with no leather or cork washers – and it was watertight enough to swim the English Channel, which Ms Mercedes Gleitze famously did the following year, wearing a Rolex Oyster around her neck.

Proper diving watches were pioneered in WWII by brands such as Panerai, but the familiar templates still followed today were laid down in the late 1950s and early 1960s by Rolex, Blancpain, Doxa, Omega and others. Building on the essential structure of the screw-in case, brands have improved the build quality of both their cases, the rubber O-ring gaskets that sit snugly between these external interfaces and the screw-down crowns and chronograph pushers that guard the most obvious entry points into the watch.

Modern dive watches may not be essential tools for divers, either professional or amateur, but their build quality is second to none, which, combined with their adherence to a largely unchanged design language, explains their enduring popularity.

Water-resistance is an issue for all watches, however, and while your average perpetual calendar or monopusher chronograph was never intended for seafaring use, improvements in materials, tolerance levels and watchmaking processes across the board mean that even the daintiest of watches can boast some level of protection against the elements, although, as we’ll see, how that’s communicated is often less than clear.

02. How is water-resistance measured and tested?

This is where a lot of the confusion creeps in. Despite the authoritative, numbered ratings you find on many watches, there is no universal standard for measuring water-resistance. This is why watches marked 10m, 30m or 50m are often seen as misleading. The numbering convention derives from its use on dive watches, but it absolutely does not mean you can submerge your watch to these depths, or anything close.

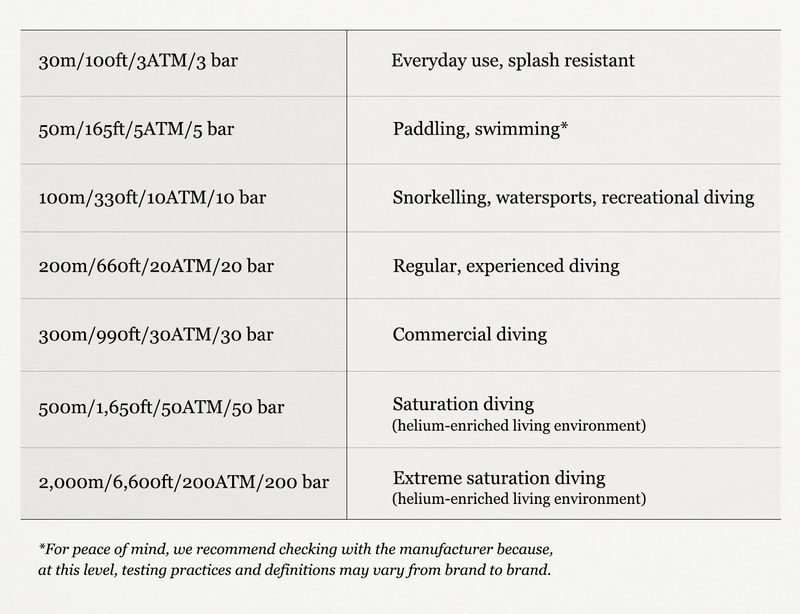

Water-resistance has historically been measured in metres or feet as an indicator of how deep a watch can go before water forces its way in. This still happens, but is often accompanied by an equivalent measure of pressure, expressed in terms of either atmospheric pressure (ATM) or bar. Essentially, 10m of distance below water equates to one bar, a metric unit of pressure (100,000 Pascals to be precise) that roughly equates to oneatmosphere, the mean sea-level atmospheric pressure (101,325 Pascals). So 100m water resistance is often referenced as 10ATM and so on.

Watch brands subject their watches to pressure tests either in air or in water (depending on the level of pressure and whether they are dive watches or not). For the latter, they test for rapid changes in pressure, as well as changes in temperature, and check that, within a set time after leaving the water, no condensation forms on the inside of the sapphire crystal.

We outline what you can and can’t do with a watch at each depth rating below. The important point to note is that below 100m, the depth ratings aren’t really depth ratings at all. They’re expressed that way because there is no handy, agreed term for describing the water-resistance of watches that aren’t explicitly designed to go in the water. Which brings us back to dive watches.

03. What exactly is a dive watch?

If you want to call something such as the Rolex Submariner, Omega Seamaster or IWC SCHAFFHAUSEN Aquatimer a dive watch, it has to meet the requirements of an internationally agreed standard (ISO 6425). Introduced in 1996, it dictates a minimum of 100m water-resistance for scuba worthiness plus the ability to time dives with a uni-directional rotating bezel ring, luminous legibility in the murky depths from a distance of 25cm and even end-of-life indication in case the watch is battery powered.

Dive watches are tested to their stated water-resistance plus 25 per cent to be certain their performance will live up to the manufacturer’s claims. So a 300m watch has been subjected to 375m (or, more accurately, 3.75ATM of pressure) in testing. In direct contrast to watches marked 10m, 30m or 50m, a dive watch marked with 100m of water-resistance or more is absolutely capable of being submerged in the stated depth of water. This, we agree, does not help with the confusion and is what leads a lot of people to assume that a 100m watch is perhaps only just good enough for swimming. Where there is a slight grey area is the existence of 100m-rated watches that are not explicitly dive watches, ie, they haven’t met the ISO standard (usually for other reasons, such as they lack the rotating bezel). These would be fine for swimming, snorkelling, etc, and would almost certainly survive a scuba dive, but for other reasons, they may not be watches you would want to take diving. Plenty of chronographs, for example, carry 100m water-resistant labelling, but don’t have screw-down pushers. You don’t really want to swim with a leather strap, either.

04. What are the typical depth ratings and what do they mean?

05. What’s the deal with helium?

Ah, yes. Another can of worms. Helium-release valves only really concern elite saturation divers. During weeks of continuously shuttling between the extreme depths of, say, an oil rig construction site and similarly pressurised living quarters with a helium-rich ambient gas mix (avoiding a drawn-out daily depressurisation process), the tiny helium atoms leak through even the tightest of seals on their watches. Once the job’s completed and the divers commence depressurisation, the helium inside their watches can’t escape fast enough, which sometimes leads to the dial’s crystal dome popping out violently.

Rolex’s simple, now widely adopted solution was invented in the 1960s at the behest of French outfit COMEX: an inside-to-out valve, generally embedded at the 10 o’clock position of the case ring, which lets any accumulated helium gas escape. So, unless you’re a commercial diver spending days or weeks underwater, you don’t need a helium-escape valve.

06. What about dynamic water pressure?

This is the idea that because watches are tested in controlled environments, without moving around, they are subject only to static pressure and, so the argument goes, they are not as water-resistant as they say they are when taken out into the real world where the water moves around – dynamic pressure. This is, we have to insist in the strongest terms, not a real argument.

Watches rated to less than 50m/5ATM may well be more susceptible to water ingress if vigorously sloshed around in the water, but it is a moot point because these watches shouldn’t be immersed in water at all.

Even the most powerful Olympic swimmer would not have the strength to move their arm through the water with enough force to exert significantly more atmospheric pressure on the watch’s water-resistant seals. Others have done the maths on this one. Moving a watch underwater at 10m/second – ie, pretty damn fast – results in the equivalent of 0.5ATM additional pressure. In other words, a difference of 5m depth. Given that even the most seasoned scuba divers rarely go deeper than about 30m, the effect of movement in the water on a 100m-rated watch is clearly irrelevant.

The argument also fails on a common-sense level. If you think swimming causes enough extra pressure to break into a dive watch, we would have seen hundreds of divers’ watches fail over the years. Instead, the world’s top dive watch brands have built a reputation for reliability that spans half a century. Moving around underwater is what they were built for and it’s what they’re good at.

07. How should I take care of my dive watch?

Most water damage to watches is the result of user error or poor maintenance. Make sure the crown is screwed in before you go under and don’t operate the chronograph underwater. Less obvious, but important: get the rubber gaskets checked and replaced regularly. They will degrade over time and render the watch vulnerable to water.

The irony of water-resistant watches is that most of the over-engineering is to get you just a certain distance down beyond which you needn’t worry, because the water pressure compresses a watch case and its crown tighter than ever. This is why Panerai fits its Luminor and Submersible watches with a levered crown guard – to hold the crown in tight at relatively shallow operating depths of 15 to 30m, where any inadvertent shock could still render its gaskets vulnerable to leakage.

“The deeper you go, any watch actually becomes more pressure-resistant as the gaskets are ‘squashed’ onto the sealing surfaces,” says Mr Michael Bellamy, head of after sales and training at British watchmaker Bremont. “The biggest risk to making the watch vulnerable is not testing or replacing the rubber seals on a regular basis [a straightforward, quick and affordable process at any high-street service centre]. Exposure to saltwater, chlorinated water and oxygen degrades these seals and the sealing surfaces they are compressed against. This is known as crevice corrosion.

“For commercial divers a test and/or replacement is recommended annually. For average swimmers, it would be more like every two years.”

Chlorine can inhibit steel from forming its protective “stainless” outside layer, which can then lead to corrosion and seal hardening. As for salt, just think of what a typical shipwreck looks like, sitting on a seabed. Rinsing watches in fresh water immediately following exposure to chlorinated or salt water dramatically reduces corrosion.

“Other chemicals can affect the seals, too,” says Mr Bellamy. “Anything from perfume, bleach, through to some antibacterial detergents. Usually these chemicals are in solution. The water evaporates and leaves a concentrated chemical residue on the seal. This is why it’s best to rinse your watch in tap water following exposure, to flush away the chemicals.”