THE JOURNAL

It is not often you have to pester someone to give them a top-notch watch. “I had this lovely white-faced Speedmaster and remember when the head of TAG Heuer offered me one of their watches,” says Mr Ross Lovegrove, the product designer who took charge of “curation and creation” at TAG Heuer during the 2000s. “I told him that I had a watch already and flashed the Omega. It was if I’d shown the cross to the devil.

“He said, ‘Why don’t you have another watch?’ And I said, ‘Because I couldn’t wear two at the same time.’ Then he asked if I had a son. ‘For him?’ he suggested. I pointed out that my son was five. He persisted. In the end I just said, ‘OK, OK,’ and took the most expensive one TAG Heuer made. I gave it to my brother. They loved that.”

Lovegrove thinks long and hard about the things in his environment. And the things he introduces to ours. Best known for using the latest technology to create the futuristic, organic forms that have become his signature – from fragrance bottles to bicycles, chairs to lighting, bathroom sets to speakers, staircases to concept cars – along the way the Welshman has helped shape products for Sony, Apple, Motorola and Renault, among many others. His designs feature in the permanent collections of MoMA in New York and the Vitra Design Museum in Germany. He pioneered the use of 3D printing in design. He cannot give details, but his most recent client is Nasa.

“A watch isn’t a watch so much as an expression of competence and a kind of body ornamentation”

Not, he says, that he can remember half the things he has designed, not because of their lack of quality so much as his fixation on designing for the present, for tomorrow.

“There’s a certain level of design now [being celebrated] that amounts to so many designers putting out a glass lamp, a wooden stool, a velvet chair – a lot of that very analogue, decorative type of thing – and I don’t want to be part of that,” Lovegrove says. “Where design is now is in space, in science and innovative engineering, in pushing new frontiers. That’s still design, of course, and that bothers me because the debate seems to revolve all around the fairly ordinary, repetitive stuff we see around us every day. There are incredible materials that, in the hands of the right people, can make for a real, national cultural thrust. But so much of the design world is just about commercial exchange.”

That’s why, even when employed by TAG Heuer, he kicked back against some proposals. Charged with designing a golf watch, the first thing Lovegrove did was to point out that nobody wears a watch while playing golf.

“But then I realised that the project was an opportunity for me to investigate lightness, which meant we ended up with a 55g shock absorbent watch in titanium, with a clasp integrated into the case,” he says of his ground-breaking timepiece. “What I still think is so fantastic about watches is that they’re really modern in that they harness such an extreme level of complexity. A watch isn’t a watch any more so much as an expression of competence and a kind of body ornamentation.”

Or, for Lovegrove at least, it was. He wore his golf watch in, day out. Then he had a revelation with a masseur at the Swissotel in Chicago. This masseur was, Lovegrove remembers, “an eastern European guy who had such amazing, fundamental control of these magnificent arms. And I realised during this massage that, in the way he wore no jewellery at all, he looked so free in his world, free to create, free to do his thing. And from that moment I didn’t wear a watch. I didn’t even wear a ring.”

So his golf watch, and his 2001 titanium and silicon Hu watch design for Issey Miyake, may both be collectibles now. Just not for him. “I don’t get that idea of collecting cars or wine, cigars or watches,” he says. “That’s just so predictable to me.” That does not mean his appreciation for what he considers good watch design, or simply good design, is any less enthusiastic. He just wants to see what he hasn’t seen before.

“We need to blow the lid off the whole world of design”

“Design is a vector of the forward-leaning transformation of civilisation,” he says. “It’s all about new, new, new. Or it should be. That’s why I’m in this field – for the unseen, the otherworldly, the ‘wow, what’s that?’ that comes out of human imagination and the skill then to transform it. Without that kind of design, society would lose that extra litre of air it breathes every day. And the fact is that materials are more or less inert until they’re transformed. Take sand, rock, some alloys, oil, polymers and they can be transformed into an incredible object like a car.”

That is why, somewhat contrary to the fears expressed by many creatives, Lovegrove cannot wait to see what objects might be dreamt up by artificial intelligence (AI). Many years ago, before AI, he proposed using algorithms to collect all the available info on a particular kind of design or design principle in order to propose what objects should exist, given all the ideal parameters of lightness, energy use, recyclability, dematerialism and so on, but do not yet. The algorithm would in some sense qualify the right for objects to exist.

“There would still be a need for some human pixie dust sprinkled on top, but something needs to underpin the industrialisation of numerically large-scale objects because we’re ticking along in a copycat culture making lots of ‘nice’ things that nobody needs,” he says. “So I don’t just not have any fear of AI, I welcome it. I think we need to blow the bloody lid off the whole world of design. We need a predator to show us the real potential.”

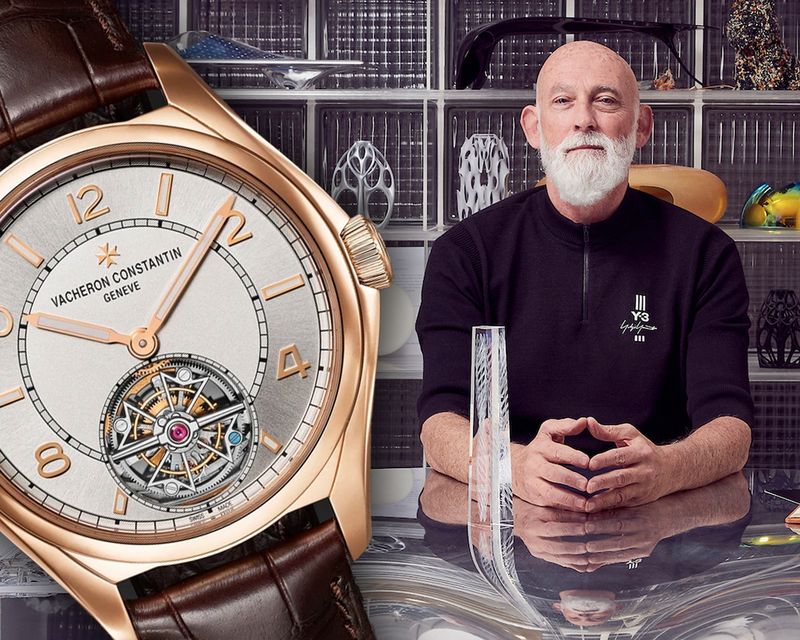

01. For special occasions

Vacheron Constantin Fiftysix Automatic

“The revelation of layered complexity in this timepiece is exquisite and communicates a respect for the craft of Swiss watchmaking,” Lovegrove says. “But [unlike so many watches that attempt this kind of approach], it’s wearable, too, in the sense that the colours of the mechanism’s layering are sophisticated yet homogenised. At a distance it pushes back, while in a more intimate proximity its intensity is hyper modern.”

02. The keeper

Gerald Charles Octavia Garcia Maestro 8.0 Squelette

“What I love about this model is the way light passes right through the open worked skeletonised mechanism so the colour of your skin influences the perception of the watch. There is so much asymmetry, even in the case, and that gives the watch a sense of being neither obviously new nor old, just unusual, and all the more so when so boldly put on that contemporary coloured rubber strap. Wearing this would tell the world that you’re deeply into sourcing truly individualistic objects.”

03. For every day

Bovet Récital 27

“Everyone seems to be wearing an Apple or some kind of smartwatch these days. I can understand how it’s defined a new universal digital market, but I think it’s banal. Something I’m working on right now is influenced by the way Bovet fuses technology and craft while also evolving early horological creations. I think it would almost be an act of defiance to wear a masterpiece of watch design like this every day. It would be a reminder to always excel and raise the bar – on the art and design you create, the food you eat, the music you listen to, the wine you drink and the way you conduct your cultural existence.”