THE JOURNAL

Grand Pavilion Penthouse at The Berkeley, London. Photograph courtesy of The Berkeley

Inside the new crop of luxury penthouses catering to the mega wealthy.

When American fashion designer Mr Zac Posen flew to London for the royal wedding (and to attend to Princess Eugenie’s second wedding dress, which he designed) he stayed at The Berkeley, the Knightsbridge stalwart famed for its Blue Bar and celebrity patronage. From the photo he took through the enormous window of a church at sunrise, we can deduce the room he stayed in; one so capacious and lavishly appointed that it – and the category to which it belongs – is helping to redefine the penthouse.

The “super suite”, of which The Berkeley’s vast Crescent Suite and Grand Pavilion Penthouse are just two recent examples, is part of an arms race in which luxury hotel brands are pumping huge money into ever larger spaces. These super-sized rooms compete with each other for the custom of a burgeoning demographic of high-net-worth travellers – and against the flourishing market for premium home rentals. “Large suites used to be about just filling more space with more furniture,” says Mr André Fu, the Hong Kong-based designer behind the Berkeley’s Grand Pavilion, as well as the Andaz Singapore and Four Seasons hotels in Japan and South Korea. “Now it’s about creating aspirational residences that have the quality of home but also something out of the ordinary.”

At the Berkeley, this means 220sq m, with a wraparound rooftop terrace, a fire pit overlooking Belgravia, as well as two living rooms, two bedrooms and a bar to which the Blue Bar’s mixologist can be summoned by a “signature service liaison” (the ubiquitous butler has been rebranded in this new era). The dining table seats eight and can be laden with dishes from Marcus, the hotel’s Michelin-starred restaurant. The price per night for either suite: £18,000 (including breakfast, one assumes).

The Sterling Suite at The Langham, London. Photograph courtesy of The Langham

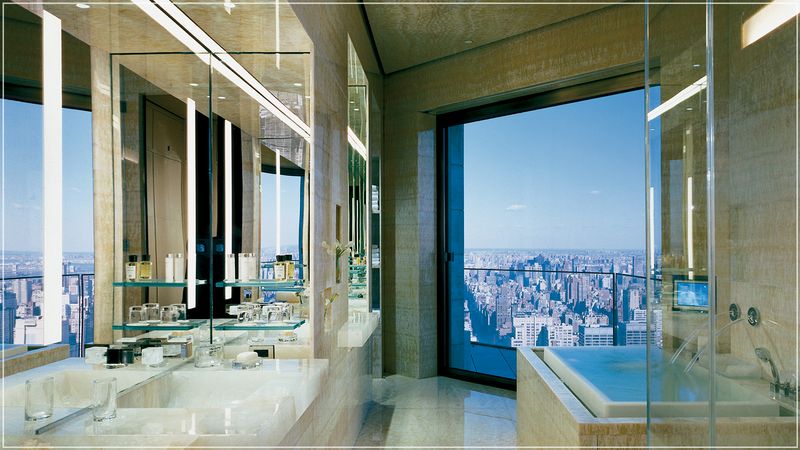

Other super suites that have mushroomed in the past five years are bigger still. The Sterling Suite at The Langham in London occupies 450sq m and has six bedrooms. The 400sq m, $55,000-a-night Ty Warner penthouse at the Four Seasons Hotel New York occupies the building’s entire 52nd floor. It includes a library with a grand piano, its own spa, three private lifts and the exclusive use of a chauffeured Rolls-Royce.

This is not just a trend in luxe epicentres such as New York and London; a 200sq m, $10,500-a-night suite at the new The Retreat at the Blue Lagoon, just outside Reykjavik, is so exclusive the hotel’s website doesn’t list it. It has its own spa including a private bathing area in the lagoon itself, as well as a fully-equipped kitchen and sauna.

Large rooms have always crowned luxury hotels. But the suites, often named “royal” or “presidential”, were typically built for sovereign families and nation leaders. They could be occupied by owners or dignitaries at a whim, or otherwise perhaps reserved as upgrade fodder for prized corporate clients or A-listers. “They were loss-leading and rarely occupied,” says Mr Piers Schmidt, a veteran luxury consultant behind London-based agency Luxury Branding.

Little attention was paid to amenities and interiors beyond a suitable acreage of velvet drapery and gold leaf in which to receive your courtiers and commercial hangers on. Where large groups or families needed to be accommodated, an entire floor might be taken out, but corridors were never meant to become part of a living space and there would be no real kitchen. “It’s not good enough any more to have bigger versions of regular rooms, or lots joined together,” says Mr Simon Rawlings, creative director at David Collins Studio, the luxury interiors firm behind some of the grandest hotel spaces.

Ty Warner Penthouse at Four Seasons New York. Photograph courtesy of Four Seasons New York

Mr Rawlings says The Apartment at The Connaught, designed by the late Mr David Collins and revealed in 2013, helped redefine the modern penthouse. Its name signalled its intention to feel, well, less “hotelly” and more like the kinds of homes to which its guests had become accustomed: warmer colours, less beige, gilt and marble, and a more logical layout centred around living spaces rather than bedrooms. “The Apartment had a personality and that felt exciting at the time,” Mr Rawlings says.

Five years on, David Collins Studio has shifted up several gears. “Now we’re designing security rooms, personal gyms, wine cellars, make-up rooms and more facilities for children and staff,” Mr Rawlings adds. Recent projects include a top-secret, “next-level” suite in the Middle East and a sky-high penthouse in Melbourne. This December, the studio will reveal the 660sq m Owner’s Villa at the Delaire Graff Estate in South Africa with four bedrooms and art from the collection of Mr Laurence Graff, the British billionaire jeweller. “It’s a private home but it’s also a hotel room with enough space for drinks for 200 people,” Mr Rawlings says.

Two things are driving this change; the rich are getting richer, and their lifestyles and expectations of quality and privacy are shifting, too. “They are true global citizens, but don’t want to sacrifice the domestic lifestyle they are used to in their large primary homes,” Mr Schmidt explains. Private lifts have become de rigueur (no longer the dash from an underground car park via the kitchen as of old) and service has become so complete, with Michelin-starred in-room cooking and private bars, that guests rarely need go anywhere else.

The Apartment at The Connaught, London. Photograph courtesy of The Connaught

Mr Knut Wylde, general manager at The Berkeley, says his super suites no longer attract only celebrities and sheikhs, but philanthropists and big fish in the art and music industries. They might want to host business meetings, drinks receptions or after parties, or use a private powder room and attached dressing room to prepare for multiple interviews or appearances. They prefer to eat away from prying eyes – or depressing room-service cloches. “Privacy is a huge element of this,” Mr Wylde adds. “These are people who are very aware of the mobile phone on the next table.” High-net-worth individuals who travel extensively more often now take their families with them, he says, and want to stay somewhere homely.

This new residential aesthetic fuels and responds to the rise of luxury home rentals inspired by the high end of the Airbnb revolution. Firms such as Onefinestay and Plum Guide scour the world for the grandest homes and apartments. Mr Rawlings suggests super-suite guests are not the same demographic, but Mr Wylde sees a threat. “I think if someone says it’s no competition they’d be lying to themselves,” he says. “That’s why we incorporate a lot of other apartment features, be it more storage, or washer and dryer machines for guests’ staff to use.”

“We need to be very mindful of what’s happening out there,” adds Mr Luca Allegri, general manager at Le Bristol in Paris, where large signature suites have replaced several older rooms, albeit with more traditional designs. “I strongly believe it’s the service that in the end will make a client return.”

Guest relations in these suites have reached new levels. Mr Wylde travels to New York once a year to present one particular guest with a gift. “I’ll also have dinner with his assistant who will go through his requirements,” Mr Wylde says. The guest has always stayed in The Berkeley’s best suites, but preferred the sofa and rug in an older one. “We keep them in one of our warehouses and put them back for him,” Mr Wylde adds.

Grand Pavilion Penthouse at The Berkeley, London. Photograph courtesy of The Berkeley

What hotels seek for their biggest suites is loyalty – and long stays. Prices are high and typically non-negotiable, making the penthouse highly profitable, despite often being empty. Mr Wylde says all four of his signature suites, including the new giants, are taken as we speak. “And they only need to be occupied a third of the time of a luxury suite to generate the same revenue over the year,” he says. His longest stay has been four months, and two months are common, but there’s no minimum. “If you wanted one tomorrow for one night, no problem, but if you wanted a night during Wimbledon next year, we might have to have a different conversation,” he says.

The race to create ever more refined “homes” within hotels is blurring the very idea of a hotel. That move is unlikely to stop at the super suite. Mr Schmidt has just returned from Portugal where he is consulting for a pair of billionaires who travelled for 18 months after selling a big business. They are now developing suites in a property in Porto as part of a plan to take the new model to “second” cities, where luxury competition is less fierce. Mr Schmidt says the men are among a number of highly financed entrepreneurs scouting for similar opportunities. He predicts that many of these new developments will have the membership structure: “Soho House for the uber wealthy,” he says.

Meanwhile at The Berkeley, where Mr Wylde is freshening things up, his best suites rarely get social-media endorsements. But, just two days before Mr Posen checked in, Ms Gwyneth Paltrow Instagrammed the same sunrise view of the church from her Pavilion suite. The actor was in town to promote her new Goop pop-up store, across Hyde Park in Notting Hill. “She was supposed to have an interview in a private room and afternoon tea with a fashion designer in the restaurant, but in the end felt so comfortable in her suite that she said, ‘I’ll have everyone come to me,’” Mr Wylde says. “This is how it works now.”

[_**For more travel recommendations, go to MR PORTER’s Style Council

**_](http://www.mrporter.com/style-council)