THE JOURNAL

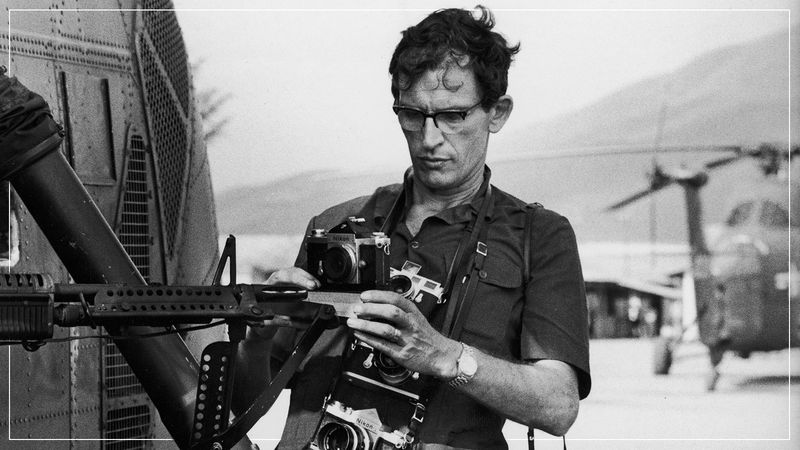

Mr Larry Burrows in Vietnam, 1965. Photograph by Time Magazine/The Life Picture Collection/Getty Images

In praise of the most heroic photojournalists of the past century .

They are the men and women who shaped our understanding of war, who used the camera to document the brutalities, violence and suffering of conflicts in the 20th century.

The photojournalists came into their own almost a century ago. They used the medium of photography, combined with mass circulation of magazines and newspapers, to record what they had seen at the front and away from the battlefield, and to show politicians and voters what war involved. Most were driven by a passionate hatred of injustice and tyranny. They were brave, intrepid and sometimes foolhardy. Many paid for their art with their lives. Getting as close as possible to capture moments of death and suffering, they deliberately put themselves in danger. Some were shot by snipers, some stepped on mines, some were killed by shrapnel and some, such as Mr James Foley, were executed by terrorists.

A dramatic picture – of heroism or enemy brutality – could rally support more than any propoganda broadcast

Photography during WWI was difficult. Armies did not want the public to see what their troops endured or what they did. Censorship prevented publication, cameras were cumbersome and it was hard to process film quickly or safely. But 20 years later, by the start of the second global conflict, journalists had learnt how to capture the images, and papers were quick to disseminate the telling pictures. Men such as Mr Robert Capa, largely acknowledged as the founder of war photography, had trained in civil wars or colonial conquests – in Spain, Abyssinia or Manchuria. They were enlisted by democracies to tell the public what their countries were fighting for. And a dramatic picture – of heroism or enemy brutality – could rally support more than any propaganda broadcast.

Photojournalism did not end in 1945, however. Dozens of subsequent conflicts, from Korea to Vietnam, Algeria to Syria, as well as uprisings and massacres across the developing world, gave cameramen with a political conscience a chance to change the course of events. Our understanding of the Vietnam War is framed by a few single shots – the burnt little girl running naked down the street or the point-blank execution of a terrified combatant.

War correspondents could not be corralled, however. They also filmed social unrest, urban squalor, famine and ethnic cleansing. Their pictures are often high art: beautifully composed and evoking pity, fear and burning emotion. They continue to be venerated, exhibited on screens and in galleries. Here are some of the most famous war photographers of our time.

Mr Robert Capa

Mr Robert Capa on a destroyer during D-Day, 1944. Photograph © Mr Robert Capa/International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos

More than 60 years after his death, Mr Robert Capa remains the model for those who want to capture history with their camera. A Hungarian Jew who fled the Nazis, he witnessed the rise of Hitler and brought WWII and France’s colonial war in Vietnam to magazines and newspapers across the world. As fearless as he was frenetic, he travelled across Spain with Mr Ernest Hemingway, summing up the bloody civil conflict in a portrait of a dying Republican fighter. “The Falling Soldier” was published in the photojournalism magazine Picture Post and earned him the title of the greatest war photographer of his time, while still only 25. Mr Capa stormed across Sicily with US forces in 1943 and waded ashore on Omaha Beach with the first wave of US troops on D-Day. Under heavy fire, he took 106 pictures. All but 11 were destroyed in a laboratory accident in London, but the “magnificent eleven” survivors, published on 19 June 1944, are among the most famous of WWII.

Awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Eisenhower in 1947, Mr Capa founded the mighty photo agency Magnum, and became its president in 1952. In 1948, he travelled to Palestine to witness the bloody birth of Israel. In 1954 in Vietnam, where France was fighting a losing colonial battle, he got out of a Jeep to photograph advancing troops and was killed by a land mine. He was 40.

His pictures – dramatic, poignant and terrifying – have shaped our view of the 20th century. He knew generals, writers and politicians, was the lover of Ms Ingrid Bergman and has had medals struck and stamps issued in his honour. “If your photographs aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough,” he famously remarked, a maxim that cost the lives of several who tried to live up to his legacy.

Sir Don McCullin

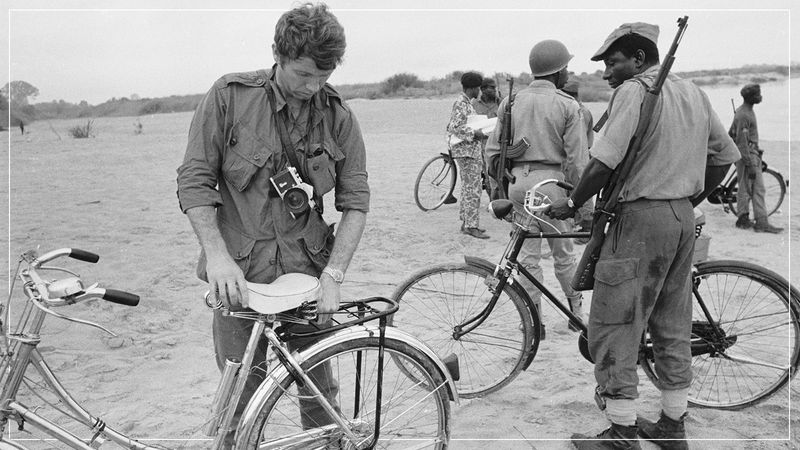

Sir Don McCullin in Nigeria during the Biafran War, 1968. Photograph by Fondation Gilles Caron/Gamma-Rapho

Sir Don McCullin is Britain’s most celebrated photojournalist, made famous by his gritty and politically charged pictures of the conflicts in Vietnam, Biafra, Cyprus and Northern Ireland and the seamier underside of big-city life, gangs and squalor. Much of his work was published in The Sunday Times Magazine, earning it and himself many awards. Now 81, Sir Don’s last assignment was in Syria, where he shot pictures of the victims of President Bashar al-Assad’s bombs. From a vast collection documenting violence over the past 50 years, his photographs have been exhibited in the Imperial War Museum and across the country. His accompanying book, Shaped By War, tells as much about Sir Don and his politics as it does about the underdogs he has championed, especially the African, Palestinian and Arab victims of conflict.

Sir Don began work as a photographer’s assistant while on National Service, and was posted to the canal zone during the 1956 Suez Crisis. Short of money on his return, he pawned his camera, but his mother later redeemed it. In 1968, a Nikon saved his life when it stopped a bullet. Sir Don said he grew up in poverty, ignorance and bigotry, and some of the poison remains within him, giving an edge and sense of guilt to his photographs of violence and injustice. He has also taken definitive pictures of The Beatles in their heyday and has, in recent years, turned to portraits and landscapes. A professed atheist, he said he has been in places where he has fallen to his knees saying, “Please, God, save me from this.” For Sir Don, photography “is not looking, it’s feeling”.

Mr Tim Hetherington

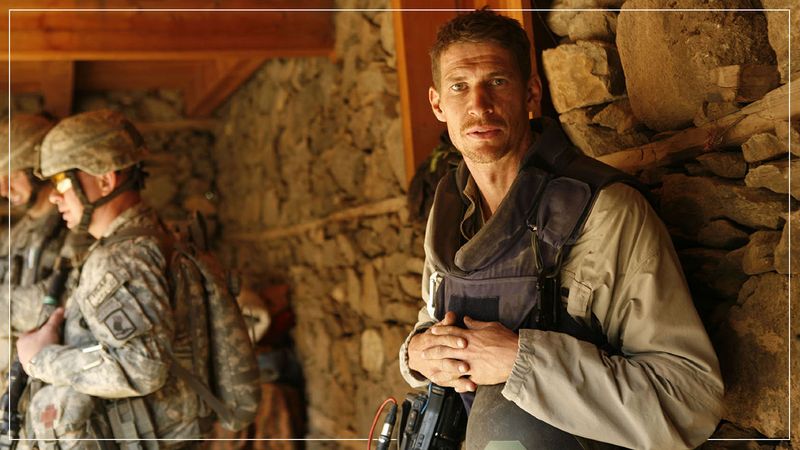

Mr Tim Hetherington in Afghanistan, 2007. Photograph by REX Shutterstock

Known as much for his films as his pictures, Mr Tim Hetherington was a rising British photojournalist whose life was cut short by shrapnel on assignment covering the civil war in Libya in 2011. He had already won numerous awards, including World Press Photo Of The Year in 2007, and had produced books, films and regular articles for Vanity Fair. His 2010 documentary Restrepo won the grand jury prize at the Sundance Film Festival in 2010 and was nominated for an Academy Award a year later.

Mr Hetherington took up photography after education at a private Catholic school and a degree in classics and English at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. Two years in India, China and Tibet convinced him that he wanted “to make images” and he went back to college in Cardiff to study photojournalism. He began work on social issues for The Big Issue, the magazine sold by the homeless, and went on to west Africa, where he spent a decade looking at violence and civil war in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Nigeria. Assignments in Afghanistan, embedded with US troops, led to Restrepo. It was dangerous, the war was out of control and, as he told The New York Times, “I was gobsmacked.” Mr Hetherington’s pictures were action-oriented, reminiscent of classic war photography. He was killed on the front line of the besieged Libyan city of Misrata. A square is now named after him in Libya. Senator John McCain, the US war veteran, sent two US flags to his memorial service in New York.

Mr Larry Burrows

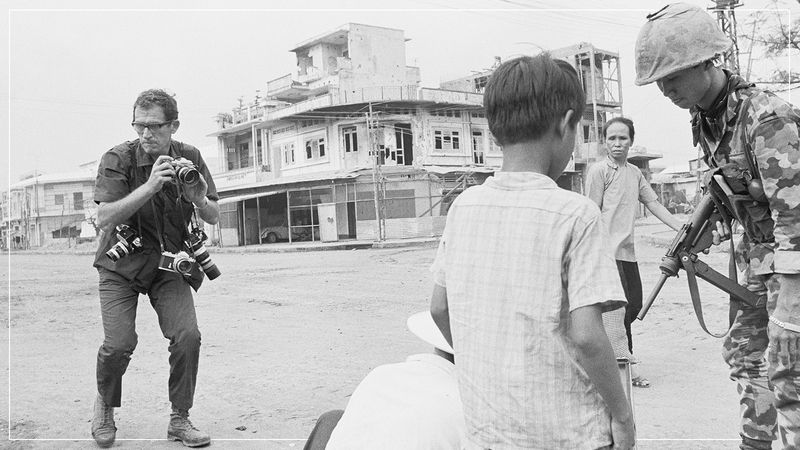

Mr Larry Burrows in Ho Chi Minh City (now Saigon) during the Vietnam War, 1968. Photograph by Mr Christian Simonpietri/Sygma via Getty Images

Mr Larry Burrows made his name during the Vietnam War, as did many journalists of his generation. The British-born photographer, who began work in Life’s London bureau, went to Vietnam in 1962, and remained there until his death in 1971. Documenting the escalating conflict, the deepening US involvement and the suffering of the ordinary Vietnamese, his work is probably the single best archive of a war that ravaged a generation and defined American politics in the 1960s and 1970s. “Reaching Out”, which shows a wounded marine comforting a comrade, tugged at America’s heartstrings; “One Ride with Yankee Papa 13”, a collection of pictures in Life in 1965, brought the war home to every US living room.

Mr Burrows had already covered military operations in Lebanon, Iraq, Congo and Cyprus. He was killed, aged 44, along with other photojournalists in neighbouring Laos, when their helicopter was shot down while they were covering the massive operation by the South Vietnamese army to destroy the communist Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese supply lines. Their remains were interred, 37 years later, at the Newseum in Washington DC. A posthumous book of Mr Hetherington’s work, published in 2002, won the Prix Nader.

His photojournalism, deliberate and meticulous, was carefully planned on the basis of his observations on the battlefield. He would spend several days on an image. His approach was very different from his contemporaries’, but, to many, his pictures better summed up the essence of the conflict. It garnered him two Robert Capa Gold Medals and the 1967 British Press Picture of the Year award.

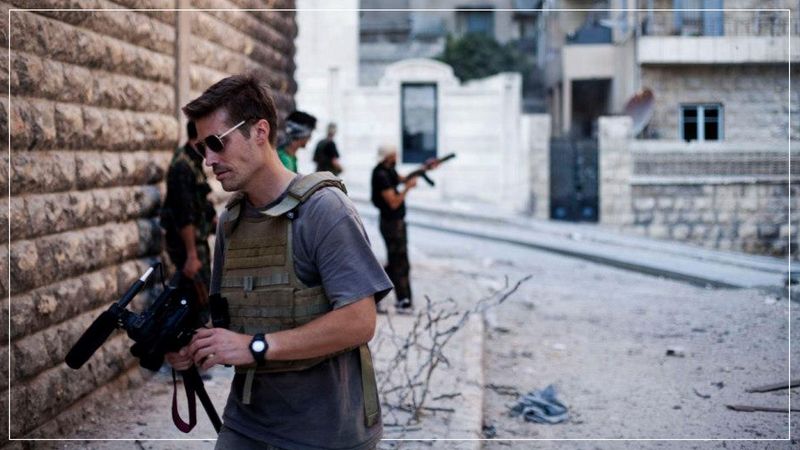

Mr James Foley

Mr James Foley in Aleppo, Syria, 2012. Photograph by Mr Manu Brabo/EyePress/REX Shutterstock

The gruesome decapitation of the American freelance reporter, filmed by Islamic State extremists in August 2014, brought home to the world the brutality of the war in Syria and the bravery of men such as Mr James Foley, who were attempting to cover it. Kidnapped while reporting for Agence France-Presse in northwest Syria in 2012, Mr Foley spent nearly two years as an Isis hostage. He was murdered purportedly in response to US airstrikes in Iraq, the first American citizen to be killed in a way designed to intimidate Western viewers of the bloody video.

Mr Foley had been captured once before, in Libya, where he was held by forces loyal to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi for 44 days while working for GlobalPost. Seized by troops while reporting from the rebel side, he and several other journalists were beaten and one was killed. Mr Foley said after his release that he had gone through many different emotions while in captivity, but rosary beads had helped him through the ordeal. He returned to Libya within months and witnessed the capture of Colonel Gaddafi.

Mr Foley began work as a teacher, switching to journalism and development projects in Baghdad in 2008. Two years later, he applied to be embedded with US troops in Afghanistan and joined Stars And Stripes. He was kidnapped in 2012, while leaving an internet café in northern Syria, and was moved many times during his captivity while desperate efforts were made to secure his release. A ransom of €100m had been demanded. A US military rescue mission to free him and other captives failed to locate them. Mr Foley was subject to mock executions and torture. His final message to his family in June 2014 was memorised by a Danish hostage, later released, and made public by his family after his death.

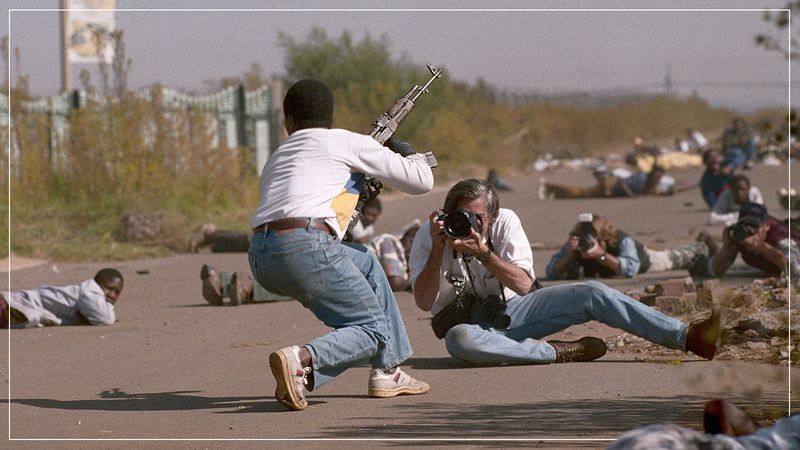

Mr James Nachtwey

Mr James Nachtwey in South Africa, 1994. Photograph by Mr David Turnley/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Mr James Nachtwey has worked with most of the main international photo agencies and covered most of the political upheavals of the late 20th century, including South Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and Eastern Europe. He has been injured several times, and survived an attack in Iraq when an insurgent threw a grenade into the vehicle where he and a Time journalist were embedded with US troops. The journalist grabbed the grenade to throw it out of the Humvee before it exploded. Mr Nachtwey filmed the devastation and the emergency medical treatment before passing out. Both he and the journalist recovered after being airlifted to hospital in Germany, and a year later he was fit enough to film the 2004 tsunami in Asia.

An American who graduated in art history and political science from Dartmouth College, Mr Nachtwey happened to be in New York during the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, and took numerous pictures of the devastation. His first assignment was in Northern Ireland, and he has since covered civil strife, social issues and war in some 30 countries, including Romanian orphanages and famine in Somalia. The human toll of Aids and TB across Africa and Asia is a special interest. He has won the prestigious Robert Capa Gold Medal five times, and is an honourary fellow of the Royal Photographic Society. His last injury was a bullet wound to his leg in Thailand in 2014. Now 68, he lives in New York.