THE JOURNAL

Five Italian creatives fly the flag for their homeland.

For those not born in Italy, the general attitude towards those who were – the 60 million or so people fortunate enough to call themselves Italian citizens – tends to be one of envy. This is a country that seems to have everything: a world-famous national cuisine, a stunning and varied geography, a perfect climate and an unrivalled cultural legacy. It also just happens to host perhaps the greatest collection of art treasures in the world, from Michelangelo’s heavenly frescoes on the ceiling of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel to Mr Sandro Botticelli’s “The Birth Of Venus” in the Uffizi, Florence. It hardly seems fair.

Little wonder then that Italians are known for having a taste for the finer things; it’s difficult not to, when you’re surrounded by so many. The country has a famously indulgent lifestyle, la dolce vita, which manifests itself not only in the national appetite for good food and fine wine, but also in an obsession with fashion. Italians are renowned for their superb sense of style, which they wear with an enviable self-assurance. It has become one of their greatest exports, with brands such as Gucci, Prada and Armani now household names.

But the Italy known internationally is a simplified version. What of the other Italy, the one that its countrymen know? To find out, we went to Rome to meet five men – an artist, a designer, a chef, a musician and a filmmaker. We discovered a thoroughly modern country whose contributions to the art world did not begin and end with the Italian Renaissance, and whose culinary scene has far more to offer than just pizza and pasta. And, although it hardly seemed possible, we left even more envious than we were when we arrived.

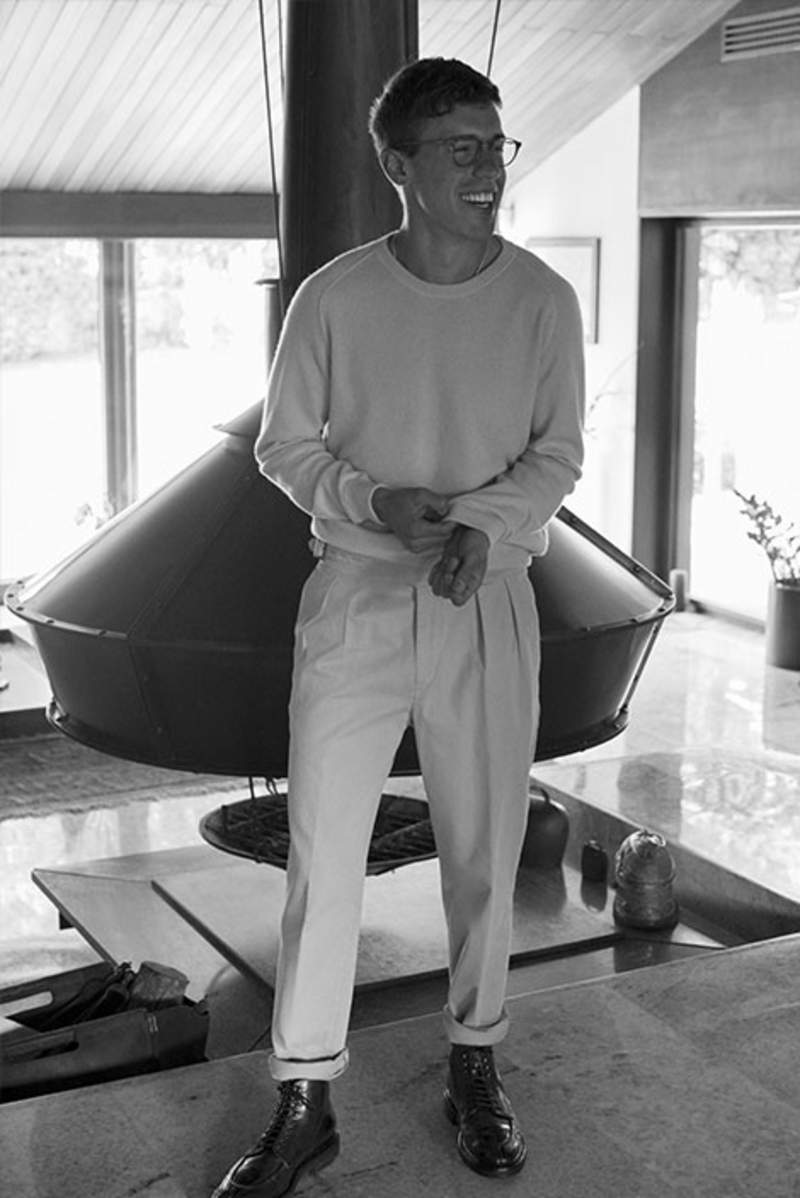

Mr Giovanni Leonardo Bassan

**Artist, 27 **

Mr Giovanni Bassan grew up in Marostica, a small town near Vicenza, northern Italy. After studying interior architecture at Politecnico di Milano, he went to Paris, where he had a fateful encounter with Ms Michèle Lamy, the wife and business partner of Mr Rick Owens. He has worked for the couple ever since, and under Ms Lamy’s mentorship he has also begun to establish himself as an artist.

As an artist, how does your Italian heritage inspire you?

I feel that to be Italian – and in a larger sense, to be European – is to be constantly surrounded by an immense history of art. It’s around every corner; it’s everywhere you look. It was intimidating in the beginning, because you naturally compare your work with all of these perfect paintings by these big Italian maestros. But rather than try to imitate them, I realised that I could take the essence of their work and apply it in a contemporary way.

In your last show, for which you collaborated with an NGO in Uganda, you painted on emergency blankets – the sort given to refugees. Do you often link your projects to a social issue?

As often as I can. I really feel that art could be an answer to the issues around us. Not the only answer, necessarily, but an answer. A while ago, I spent some time in Nepal. Shortly after I left, there was a huge earthquake. I was devastated. I wanted to go, but without proper training for disaster relief you can’t really offer much help on the ground. So, instead, I decided to do some drawings and give them away in exchange for a donation to Unicef. I said, “I don’t want the money – just give me the receipt of your donation.” I was able to collect $10,000-15,000. And I feel like it gave my art a greater purpose.

You travel extensively, both in your work with Mr Rick Owens and as an artist. How has this changed your perception of what it means to be Italian?

When I was younger, I just wanted to get out of Italy. I thought, I can’t stay here! But now that I’ve spent so much time abroad, I think I’m beginning to realise what it actually means to be Italian. Immersing myself in these different cultures, I started to see that the things I grew up thinking were normal aren’t necessarily normal to others. The way we hug and kiss when we greet one another, for instance.

What do you think the essence of being Italian is, then?

It’s the little things. It’s a sense of slowing down and taking your time. Enjoying each step. It sometimes feels like I’ve got a million things to do, but I still make an effort to enjoy each one.

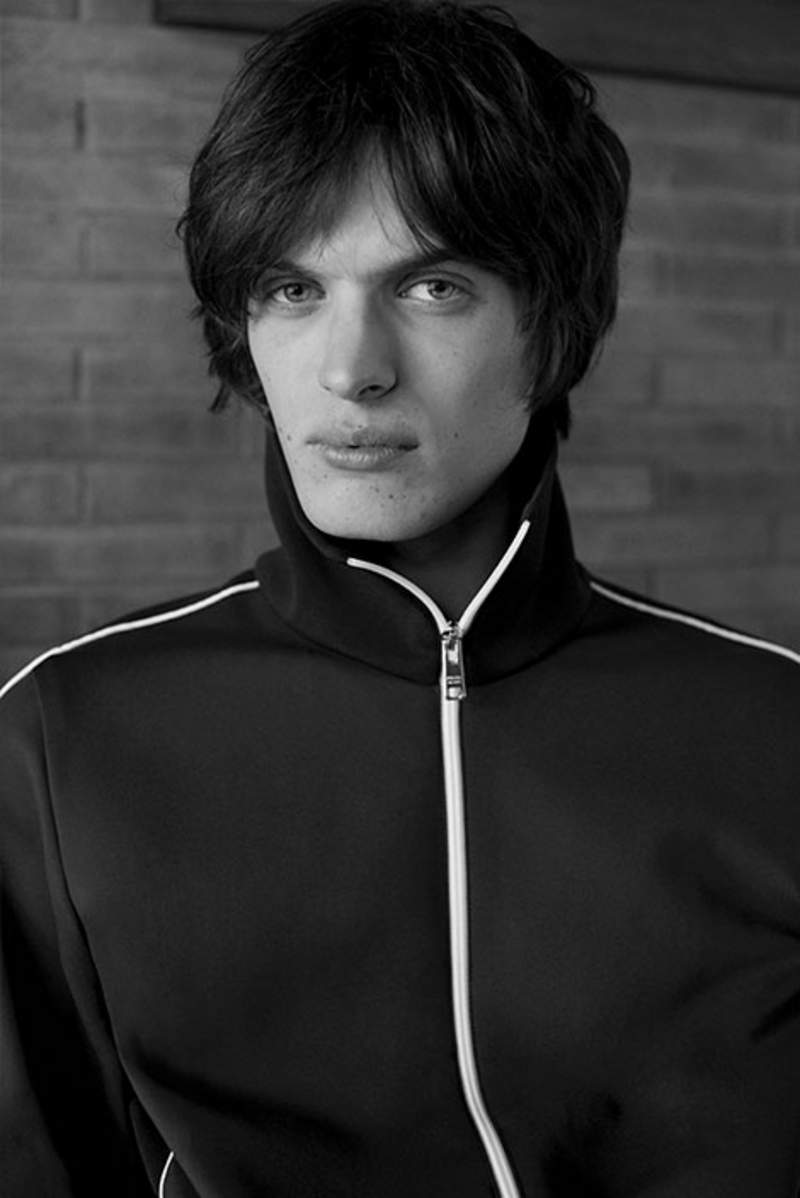

Mr Alessandro Mancini

Filmmaker, 26

Mr Alessandro Mancini is a filmmaker who works under the pseudonym Alxssvndroman. He made his name directing behind-the-scenes clips and music videos for Redman and the Wu-Tang Clan. Back in his native Rome, he has worked extensively with Dark Polo Gang, a popular trap hip-hop group. He has spent the last year working on a documentary about the lives of Italian boxers in Marcianise, an industrial town on the outskirts of Naples.

A lot of people might not be aware that Rome has a hip-hop scene.

It’s true. After I came back from tour with Redman, a few friends of mine started a movement called the 777 Gang. When I first heard the music, I knew they’d be big – but they needed a vision to match. That’s where I came in.

Describe the music.

In terms of the sound, it’s hip-hop evolution, like Young Thug. But Italian trap is about more than just the sound. It’s rooted in Rome’s urban subcultures and youth culture. We’re not trying to create some fake imitation of American trap music, we’re trying to create Italian music.

How do you capture that in your music videos?

It’s about mixing the old and the new. For “Sportswear” by Dark Polo Gang, we shot the video in Holypopstore, one of the biggest sneaker stores in Rome. But we also shot against some classic Roman architecture, too. That video has done 14 million [now 15 million] on YouTube.

Italy, and Rome especially, has a great deal of history. Is it a good place for creatives?

Yes and no. I grew up in the city centre. My father worked on renovating historic Roman palaces. That’s what comes to mind when people think of Rome. They think of history, of the past. But I don’t just want to live in a museum. You know Cinecittà? It’s a famous movie studio. They shot a lot of great films there over the years. Now, half of it is an amusement park.

Does it feel like the opportunities are limited compared with, say, Milan?

Before the Dark Polo Gang, nobody was making good hip-hop music in this city. But all it takes is a spark.

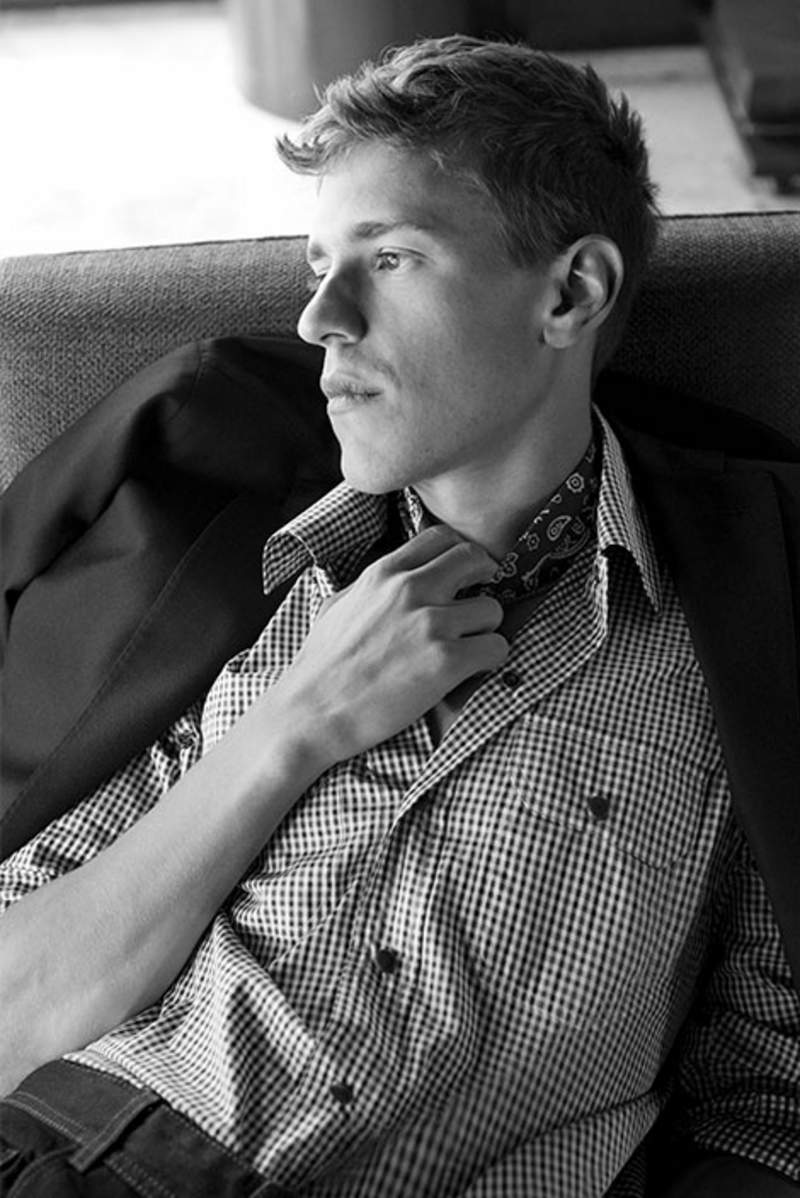

Mr Lorenzo Sutto

Musician and model, 21

When the music-obsessed Mr Lorenzo Sutto skipped school to attend an Arctic Monkeys gig, he didn’t expect to come back home with a modelling contract. Now living in London, he splits his time between modelling and playing guitar in his band, Red Bricks Foundation. An Anglophile and a self-confessed indie kid, his musical influences have a distinctly British flavour, with artists such as Joy Division, Mr David Bowie, The Beatles and The Clash featuring heavily. Nonetheless, he retains a strong link to his family home in Rome.

What is it about England that you find so alluring?

There’s something strange and magical about English subculture. Punks, skinheads, rudeboys, new wave… in pubs in London you can see older guys in Fred Perry polo shirts buttoned all the way up, with football club tattoos on their arms. In Italy, we don’t seem to have this. We don’t have a uniform. If I liked punk in Italy, I feel like I’d be attempting to appropriate an English subculture, I guess.

Did you appreciate growing up around so much culture and history?

Of course. It’s an amazingly beautiful place to be. Every day I’d see beautiful things.

What is the essence of being Italian?

I think you’ve got to remember that despite all the history, we’re still a young country. We were formed in 1861, and there are still massive regional differences. I’m from Rome, so my answer might be completely different to someone from Milan, or from Naples. But here, in Rome, I think it’s just about trying to make the best out of life.

Do you see yourself returning some day?

Well, I met my girlfriend in London, and then discovered that she’s actually from Rome. So maybe that’s fate trying to tell me to come home?

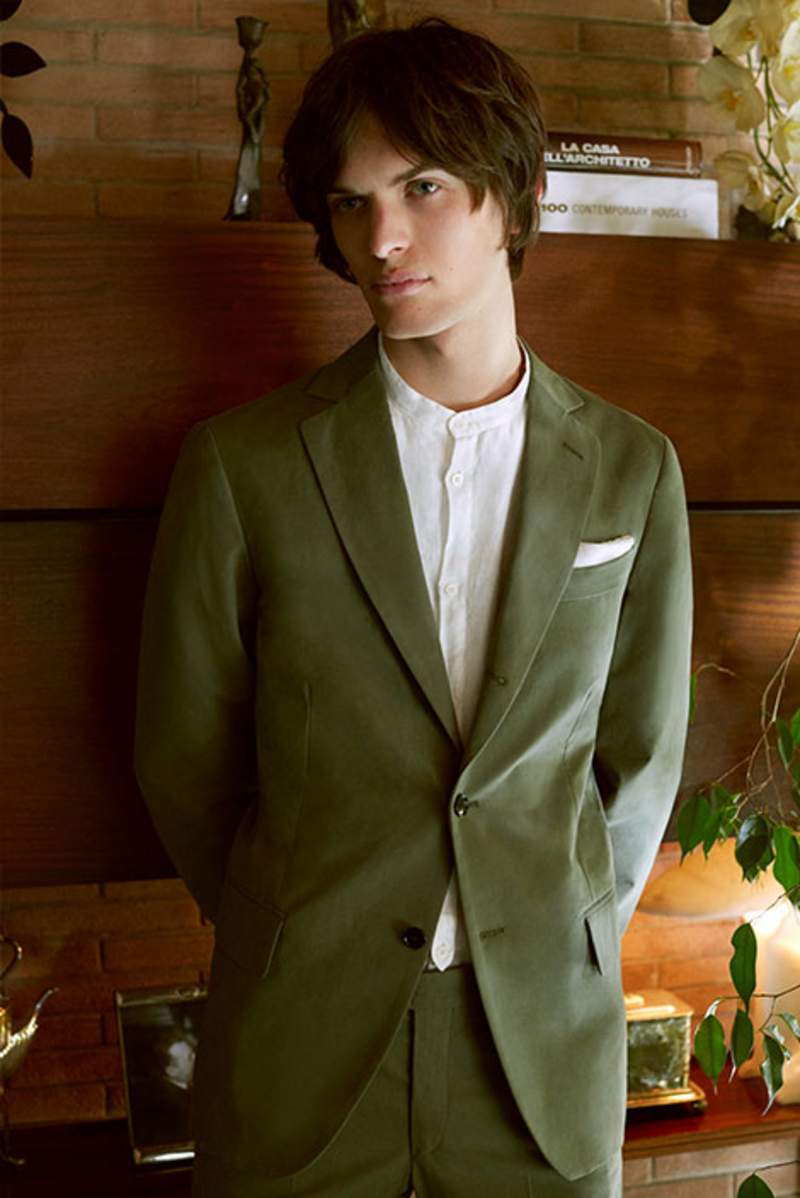

Mr Duccio Maria Gambi

Concrete furniture doesn’t sound very comfortable.

Ha! It’s not easy to make people understand that you can make furniture out of concrete, because they instantly think of the rough, grey material. But when people see the stuff that I’m creating, they change their mind. I mostly use a special kind of concrete that gives very soft and smooth surfaces. It’s white, so you can experiment with colours by treating it with pigments, and it moulds really well.

It sounds like you take an architectural approach to design.

I studied architectural engineering before I moved into interior design. As you get deeper into the field, you begin to see how the two are connected. The same principles are at play. I love the way that you can shape an empty room through the arrangement of furniture. You’re changing the nature of the space itself. When people ask me to make something special for their house, the first thing I do is try to understand what the space is like.

Is it hard to rearrange concrete furniture?

That’s another interesting thing about working with concrete: you have to really think about where you want to put it. Because once it’s there, it’s not easy to move it.

Were you inspired by where you grew up?

Florence is a really fascinating city, architecturally speaking. London is like a series of layers built on top of one another. But Florence was conceived as one entire city. It was started and finished in the same moment. It’s a Renaissance city: it has logic, precision, form. There’s a geometric relationship between elements, between empty and full spaces. And the geography itself, the way it sits in a basin, surrounded by hills, means that there are a lot of perfect views. Even after 36 years, I still occasionally see it from a new angle.

Is Florence a good place to work?

There was a time in the 1970s and 1980s that Florence was a real centre for modern design. But right now, the place to be is Milan. I used to live there about 10 years ago, but it wasn’t alive in the way that it is now. It’s really managed to capture something.

Mr Lorenzo Cogo

Chef, 31

Mr Lorenzo Cogo’s CV is a spectacular thing to behold. By the time he was 24, he had worked shifts at fine-dining restaurants on four separate continents, including The Fat Duck in Bray, Nihonryori Ryugin in Tokyo, Noma in Copenhagen and Etxebarri in northern Spain. He returned to Italy to open his first restaurant, El Coq, in his hometown of Marano Vicentino, northern Italy. A year later, when he was still only 25, Mr Cogo won his first Michelin star. Last year, the restaurant moved into new, larger premises in nearby Vicenza.

With that CV, you could have gone anywhere. Why return home to a small town of barely 10,000 people?

I knew that I wanted to start from where I grew up. To push forward the cuisine of Vicenza. That’s my mission. It would have been easier to export my local cuisine to a big city, but that’s not my job as a chef. I’m from Vicenza. If you want to taste my local cuisine, you have to come to Vicenza.

You’ve worked all over the world. How do you bring your international experience to bear without losing the authentic Italian feel of your own cuisine?

I try to respect the essence of the different food philosophies that I’ve been taught. When I was in Japan, I was taught to be very respectful of the produce, and to be very precise. To cut perfectly. But I will never use Asian ingredients or flavours. When people visit the restaurant they come from all over the world, and they expect Italian food.

What are the local flavours that you bring to the table?

I work a lot with bitterness. When you think about the region’s cocktails – the americano, the negroni – there’s a very prominent bitterness. In the northeast of Italy, we’re very comfortable with these flavours. But big food companies are taking out the original bitterness and replacing it with sweetness, in order to make the food more appealing and more addictive. What I’m trying to do is reeducate. So I’m working with bitter roots and I’m bringing charcoal back – another way of introducing bitterness to a dish.

The best restaurants in Italy tend to be away from the major cities. Why?

In Italian cuisine, we strive for authenticity. The food has to have a connection to its local environment; it has to have a terroir. The food in somewhere like Las Vegas can be fantastic. The best ingredients in the world. But it has no soul, because these are ingredients that you can find anywhere. In my kitchen, though, I have a certain flower or fruit that, 50 kilometres away, you can’t find. I concentrate on giving the customer my Italy. And that’s what makes it a destination, in the end. That’s what makes it unique and worth visiting.