THE JOURNAL

Mr Baker in the main vault, Acetate 1, which has a temperature of 10°C to preserve the quality of the film reels

In honour of this year’s London Film Festival, we explore the BFI National Archive and speak to its head curator about this fascinating collection.

“Some of the things you find here are extraordinary,” says Mr Robin Baker, head curator of the BFI National Archive. “Shortly after I got this job, I started randomly looking on shelves and dipping into drawers. Once, I pulled out these pictures of aliens drawn by Satyajit Ray, the great Indian film-maker. And I love the fact I can go and look at the film script that Carol Reed had on location in Vienna when he was shooting The Third Man.”

Indeed, the BFI’s Conservation Centre is an Aladdin’s cave of film history. It is full of artefacts to delight any movie buff (including the continuity script from Star Wars with unseen Polaroids of Princess Leia and Chewbacca), but it is also a base for the painstaking job of preserving more than a century’s worth of cinema.

The National Archive dates back to 1935 and now holds about one million titles. The collection is stored on various premises; the Hertfordshire site was built in 1985 after a donation from Mr John Paul Getty Jr. In Acetate 1, the vault where we meet Mr Baker, the temperature is 10°C, with a relative humidity of 35 per cent. Ideal for preserving film, perhaps, but not for standing still for photographs. “It’s flipping freezing,” says Mr Baker.

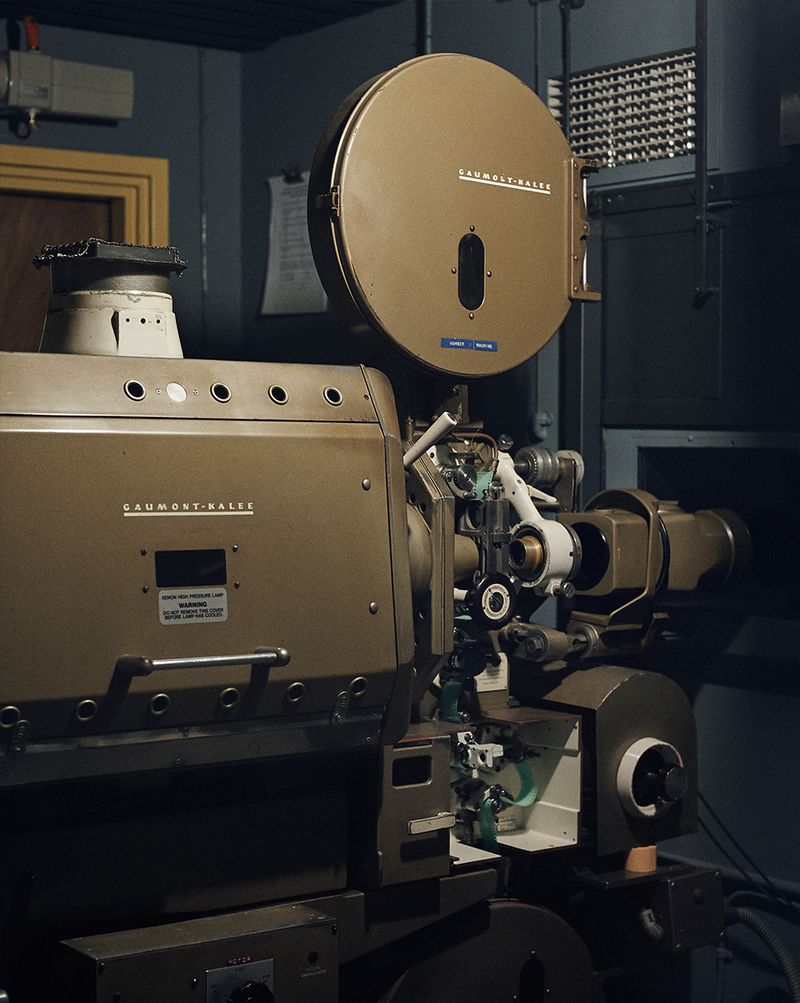

This 35mm projector was installed at the archive in 1987. It's used to check print quality and monitors about 400-500 films a year

Original film reels of thousands of movies are stored in the main vault at the BFI National Archive Conservation Centre

Mr Baker joined the BFI in 2005, having worked in the film industry for more than 20 years. In his role as head curator, he manages a 30-strong curatorial team that oversees various digitisation and restoration projects to both preserve the national archive and educate the public. “Our priority is how we make British culture accessible,” he says. On 16 October, the BFI London Film Festival will screen a restored version of the 1928 film Shooting Stars (a satirical romance set in a film studio), directed by Mr Antony Asquith, who, alongside Mr Alfred Hitchcock, is one of the great British silent film-makers.

Another of Mr Baker’s major projects, Britain On Film, is to digitise 10,000 film reels for the BFI Player by 2017. In the process, the team has uncovered the world’s earliest home movie, from 1902, and a film featuring three generations of BFI creative director Ms Heather Stewart’s family. “Film is the most tangible form of heritage there is,” says Mr Baker. “My ambition is to get as many of the films to the public as we can.”

Such meticulous work can be expensive. To fund it, the BFI relies on sponsors and events such as this year’s Luminous fundraising gala, mounted in partnership with Swiss watch brand IWC Schaffhausen, an official partner of the BFI. At the event this Tuesday, lots, including a unique IWC Portugieser Calendar Edition (which sold for £45,000), were auctioned of to raise more than £430,000. The proceeds will be used to launch Film Is Fragile, a campaign that aims to raise more than £1 million to help preserve and protect the archive.

To find out more, we headed to Hertfordshire to meet Mr Baker and investigate the corridors of film reels and machinery that the archive holds.

Mr Baker using a synchroniser to check for damage on a reel of film

How do you acquire film?

We’ve been collecting things since 1935. Britain is lucky to have one of the best film collections in the world. We have another series of vaults in Warwickshire, which is where we keep the most precious films. The temperature there is –5°C, which adds hundreds of years to the life expectancy of reels.

Why did you choose to restore Shooting Stars?

It’s set in a British film studio in the 1920s and it’s a hugely important film, one that few people know about. Our job is to transform knowledge. The composer John Altman has written a new live score for it. He has won a BAFTA, and has worked with so many contemporary artists. He worked with Amy Winehouse and he now works with Björk. I’m not just interested in film geeks, I want new people to come along. We need to tell people about films they didn’t know they wanted to see. We restored all of Hitchcock’s nine surviving silent films a couple of years ago.

What’s the difference between digitisation and restoration?

For digitisation projects such as Britain On Film, you need to feed a film into a scanner very slowly. It takes huge skill to get it in focus, frame by frame. Given how old they are, the emulsion wears off. It’s almost how you’d imagine your skin peeling. It can be very fragile. With the restoration of Shooting Stars, we had to assemble every surviving element from the 1920s, including the negative (of which only one reel survives). First, we compare each of these on a shot-by-shot basis to make sure we have a complete film. Then we work on the complex correction of images. If there is a scratch running across a number of frames when a character is smoking, for example, it’s a hellishly complex process.

If there were a fire, what would you save from the archive?

It would be Hitchcock’s early work, the films of [Michael] Powell and [Emeric] Pressburger, or work by British pioneers made at the end of the Victorian period and start of the Edwardian era. Many people don’t even know that film existed then. We can show people actual moving Victorians. It’s a real eye-opener. We also have many costume and production designs from Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes. If you look at some of the material that never made it to the final cut, it could have been far darker, more sinister and sexual.

We’ve heard the British Library can use supermarket freezers for storage in the event of a flood. Does the BFI have any special measures?

In Warwickshire, we have a master film store with a big nitrate collection where we keep the most precious negatives. Nitrate is the film stock that was used up until about 1950. It’s highly unstable and prone to bursting spontaneously into flames. It’s a very sophisticated building. If something went wrong with the heating or cooling and there was an explosion, the building is designed so that a wall will blow off and therefore lessen the impact.

What future projects you are excited about?

We’re working on a huge project to digitise a number of key British adaptations of Shakespeare. It’s the 400th anniversary of his death next year. The earliest Shakespeare adaptation is of King John from 1899. There is also a major project for 2017 for the 70th anniversary of Indian independence. We have an extraordinary collection of early Indian films. We have the Maharaja of Jodhpur’s home movies from the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, for example.