THE JOURNAL

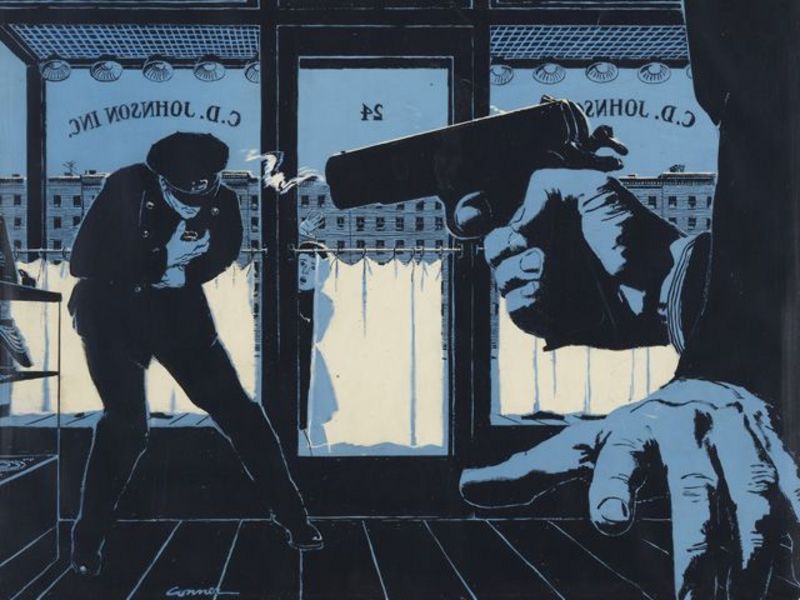

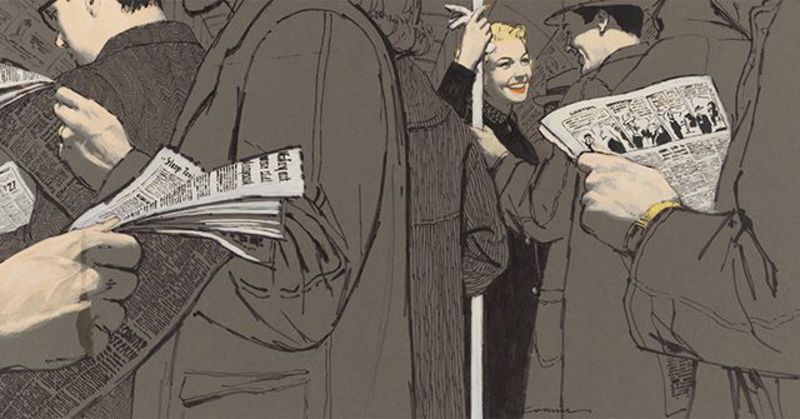

“Killer in the Club”, 1954 © Mac Conner Courtesy of MCNY

Mr Mac Conner, a spry 100-year-old survivor of the <i>Mad Men</i> era, gets a one-man show in New York.

“Don’t mind Willy. He’s my buddy. Shoo, Willy, shoo. He loves hair.”

Willy had snuck up behind me as I interviewed his owner, the American illustrator Mr McCauley “Mac” Conner. Ignoring him was not on the cards, less because of the vigorous massage he was applying to the back of my head, but because Willy, an orange and brown Abyssinian, looked as if he could have been the royal pet in the court of King Tut. He was colourful, boldly patterned and arrestingly in your face, not unlike a Mac Conner illustration.

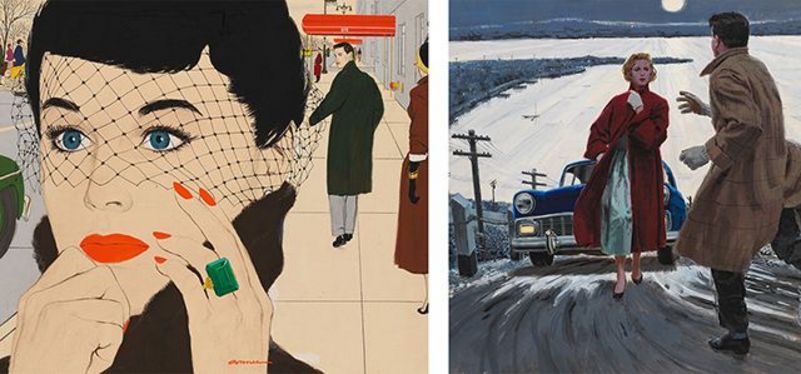

Fifty years ago, if you were a magazine reader (sort of like saying today, if you use the internet) chances were you had a subscription to a publication such as The Saturday Evening Post or McCall’s, and chances were that when an issue arrived and you opened it up, there was a double-spread featuring one of Mr Conner’s hand-painted illustrations. The caption would say something like, “He was the perfect dude wrangler – lean, rugged and immune to dames,” or “He could put anything he wanted on his expense account. There was only one drawback. No love allowed.”

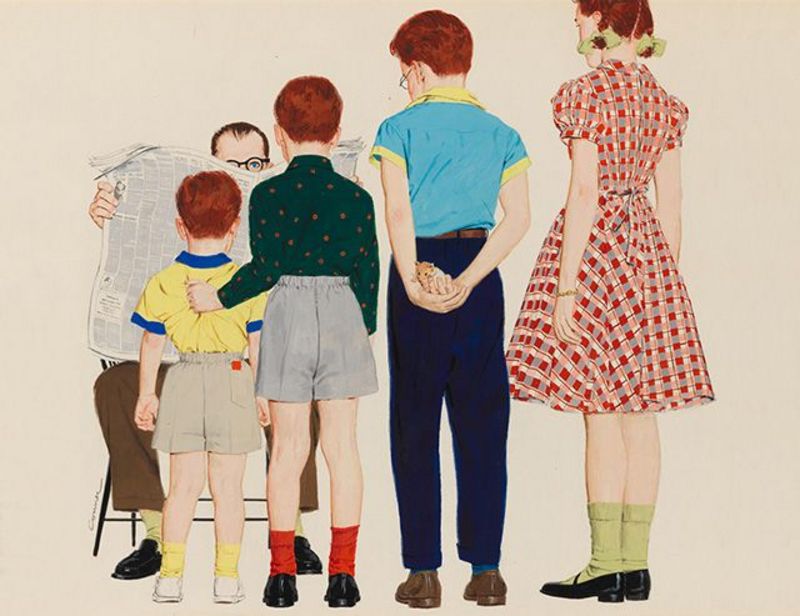

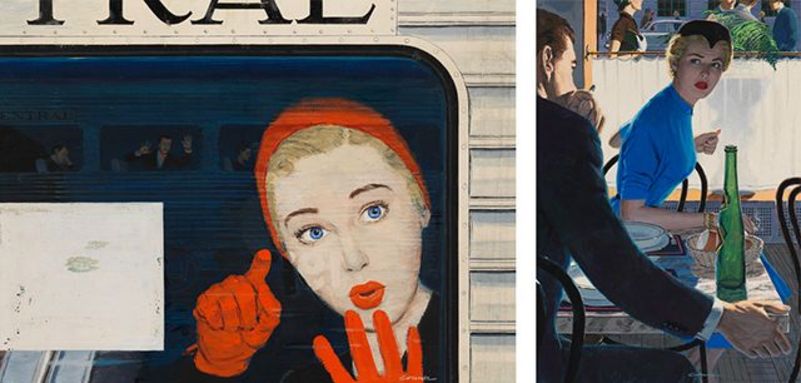

From top: ”We Won't Be Any Trouble”, 1953; ”The Trouble with Love”, 1950 © Mac Conner All Courtesy of MCNY

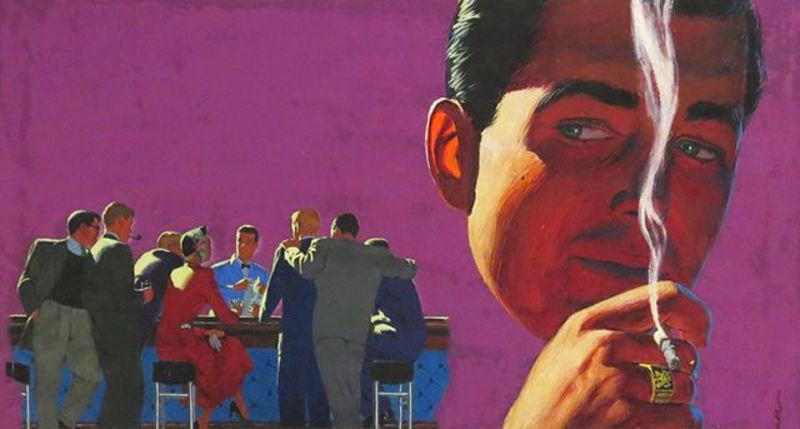

His work helped form the signature look of an era – pert women in red lipstick looking glamorous but wholesome; lantern-jawed, crisply suited men in un-ironic hats smoking cigarettes and looking nefarious. Everyone immaculate and full of vigour, despite an omnipresent element of menace or mounting tension, the tone somewhere between the illustrations of Mr Norman Rockwell and the hard-boiled novels of Mr James M Cain. (“So often he hurt her, in so many ways.”)

Thanks to Mad Men, the style Mr Conner contributed so much to developing, through scores of magazine covers and advertising campaigns (for United Airlines and General Motors, among others) has made a resounding comeback. And now Mr Conner himself is getting some long overdue recognition, with an exhibition of more than 70 original artworks at the Museum of the City of New York.

Clockwise from top: ”All the Good Guys Died”, 1950; ”Hold on Tight”, 1958; ”How Do You Love Me”, 1950 © Mac Conner All courtesy of MCNY

Mr Conner’s life these days is far from hard boiled. He lives in one of those New York apartments most of us only see in the movies, overlooking Central Park at East 72nd Street. Having turned 100 years old last November, he no longer moves easily, but in conversation it’s not hard to see why he was “perfect for the job of illustrating romance stories”, as Mr Terrence Brown, curator of the exhibition, puts it.

“He sees everything,” says Mr Brown, “especially the people around him. He’s a great observer.” Sure enough, when I came to his apartment to interview him, Mr Conner seemed less interested in talking about himself than in asking questions. “What do you write about? Who do you work for? Are you from New York?”

Mr Brown also calls Mr Conner “a bit shy. He’ll tell you, I don’t tell stories very well – I let my artwork do the talking.” But in fact, despite a throat condition that diminished his voice, Mr Conner spoke entertainingly about his career, and how he found himself perfectly poised at the nexus of art, publishing and advertising in the late 1940s.

From top: ”The Girl Who Was Crazy About Jimmy Durante”, 1953; ”Let's Take a Trip Up the Nile”, 1950 © Mac Conner All courtesy of MCNY

Mr Conner came from a modest background – his parents owned a general store in Newport, New Jersey, where as a boy the young designer spent time looking at Mr Rockwell’s covers for The Post. As a teenager he started designing covers and bringing them to Philadelphia, where The Post was headquartered. “If they didn’t want them, I’d jump on a train to New York and bring them to Liberty magazine,” Mr Conner says. Later, he attended the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art and did illustration work for the Navy during the war.

Afterwards, as a “confirmed bachelor”, according to Mr Brown, Mr Conner immersed himself in the world of clubs, theatre and Manhattan’s high life. “You had to be sharp, current and contemporary,” Mr Brown adds. “And Mac liked his Martinis, too.”

In 1956 he married Ms Gerta Whitney, also a well-regarded artist (though Mr Conner prefers to call himself a designer) and the granddaughter of Ms Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, founder of the Whitney Museum. They were married for 53 years, until Ms Conner died in 2009.

Clockwise from top: ”There is Death for Rememberance”, 1953; ”Strictly Respectable”, 1953; ”Where is Mary Smith?”, 1950 © Mac Conner All courtesy of MCNY

The New York exhibition emphasises the collaborative aspect of Mr Conner’s process, showing how a project would bounce back and forth between his easel and an art director’s offices, starting as a manuscript for a short story or the idea for an ad, then become pencil sketches and eventually a fully executed illustration. One all too easily imagines this process including drink carts, pneumatic messenger tubes and handshake deals on the 5:48 to Bedford. It also shows the publishing world at a time when it, and also the advertising industry, seemingly brimmed with confidence, secure in their dominance – a golden era. Or was it? After all, TV had arrived and would soon lay waste to whole sectors of the magazine and newspaper world. America’s media diet was becoming corrupted by new, suspicious products of dubious nutritional value, such as paperbacks. Mr Conner, after The Saturday Evening Post and McCall’s began to suffer in the 1960s, would become a cover designer for Harlequin romances, again making this exhibition a valuable lesson in career longevity.

Mac Conner: A New York Life runs until 19 January 2015 at The Museum of the City of New York. mcny.org