THE JOURNAL

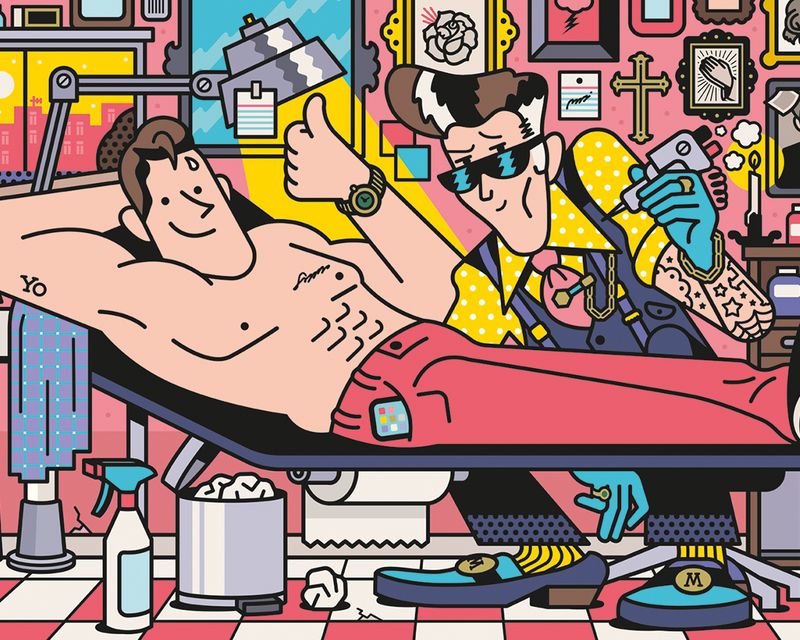

Illustration by Mr Rami Niemi

The 63-year-old man holding a needle to my chest has tattooed some of the most famous people on the planet. Mr Brad Pitt, Lady Gaga, Rihanna, Mr David Beckham. They’ve all been in the same position as I am today, reclining in a chair with Mr Mark Mahoney putting them at their ease, telling stories in his Boston brogue. Mahoney is good friends with Mr Johnny Depp. He tattooed The Notorious BIG days before he was murdered. This afternoon he’s etching ink onto someone significantly less famous and considerably less cool: me.

You expose yourself when you get a tattoo. You make yourself vulnerable. When people brand themselves with the name or, even more terrifying, the image of a loved one, I can’t help but wonder how awkward they would feel if the relationship were to end. Like proposals in baseball stadiums, tattoos can backfire when they are so romantically specific that they name an individual person. An ill-considered tattoo ages like milk.

Opting for something with no emotional connection at all, for fear of looking stupid, feels like a cop-out. I’m not someone who could get a tattoo of a stick-and-poke Smurf. Instead, what I chose for this, my second tattoo, was similar to my first, which was a fragment of a Mr Robin Williams line: “a little spark of madness”. This time it was a line of Mr Peter Cook’s, my favourite comic of all time.

I can’t take credit for having spotted it, because the line also served as the title of a posthumous book about Cook, compiled by his widow, Lin. The phrase is “Something like fire” and comes from a speech in the voice of a Cook character. “During the last few weeks I’ve been trying to think of something absolutely original and devastating. I’ve been trying to lay my hands on some idea that’ll revolutionise the world in some way. Something like fire, or the wheel.”

As well as the line being funny, I have always been in love with what I assume to be a parallel between the phrase and the way Cook worked. “Something like fire”, to me, somehow describes Cook’s way with words, his spirit, his genius. I wanted the phrase to be in my handwriting and wrote it 68 times, trying to get the “S” right. With one tattoo on the inside of my right arm, I decided this phrase would go above my left pec. Here is the fundamental dichotomy with a tattoo. You get it in order to make a statement, but often, because only a few people will see it, it’s a statement that’s uttered under your breath. (To counter this, I do strip off my top more than most people find acceptable.)

For the fifth year running, Mahoney has taken up a residency in the Mandrake Hotel in London, where he has converted a room into a studio. There are three crosses on the walls and two Virgin Mary figurines on the floor, and he has imported artwork from the Shamrock Social Club, his tattoo parlour on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles. When he enters, straight from an appointment with a tailor, he cuts a remarkable figure. Slicked-back grey hair, strong eyebrows and an outfit that immediately makes him the best-dressed in the room: a burgundy shirt buttoned to the top and high-waisted stripy brown trousers.

“I do well in London,” he says about clothes shopping. “I can get more in three days in London than I can get in a year in LA.” Calling Savile Row “Squaresville”, Mahoney buys clothes from the past. His outfit is a walking testament to his belief that adults looked truly cool in the 1960s and 1970s.

Mahoney is considered a pioneer of the black and grey tattoo. “I always think in black and white,” he says, his narrow blue eyes looking into the middle distance. “Black and white movies, black and white photographs.” When he had a box of 64 Crayola crayons as a child, the coloured ones would remain untouched after four or five days, but the black would be down to three-quarters of an inch.

Mahoney liked hanging out with tough guys as a kid. He could draw, but it wasn’t clear what he would do with his art until he went from Massachusetts, where tattooing was illegal, to Newport, where the leader of his “greaser gang” wanted to get tattooed. As soon as he stepped into Buddy Mott’s Tattoo Spot, it was “crystal clear” to Mahoney what he was going to do. “Here it is, 48, 49 years later, and I still wanna learn how to tattoo,” he says. “I still feel like I’m learning.”

“I still wanna learn how to tattoo” isn’t necessarily what you want to hear from the man about to take a needle to your body, but Mahoney takes extreme care when measuring and laying out the template for my tattoo and constantly puts me at ease. “When it’s hand-drawn, there’s definitely something magic about it,” he says about my tattoo. “Even if it’s a little bit wrong, it has a life. Tattooing’s kind of an imperfect art. The connection with the hand is real important.”

“Even if it’s a little bit wrong, it has a life. Tattooing’s kind of an imperfect art”

Though tattooing has undergone a significant shift since Mahoney was young, the fact that it was once illegal was enough to ensure his mother was never happy with his career choice. “It was like me telling her I wanted to be a burglar,” he says.

Now that it’s become almost commonplace to show off a tattoo on your wrist or forearm, Mahoney’s mother might be happier, but this doesn't mean the same applies to Mahoney. “Fuck yeah, it’s totally diluted it,” he says when I ask if tattoos are less appealing now that everyone has one. He preferred it when someone with tattoos was the kind of a person a mother would tell their child not to look at in the supermarket.

I suspect Mahoney may consider me a square, but this doesn’t stop him tattooing me. “This is like forgery, what I’m doing – copying someone’s signature,” he says as the needle buzzes. Strangely, it’s almost painless. “I think I’m a pretty gentle tattooist,” says Mahoney. “Yeah, you are,” says his assistant, Ingo, watching and learning. Throat cancer four years ago robbed Mahoney of his husky drawl, but stories pour out of him while he buzzes. “You know who don’t talk? Comedians,” he says, telling me how disappointing Eddie Murphy was. “And you know who ain’t funny? Comedians.”

When I look at my finished tattoo, written in a fine, delicate script, I think of it as a work of art. The day after my appointment, Mr Russell Brand will sit in the same chair. Mahoney is now working on another design for Adele. It’s absurd, really, that a square like me can count himself in the same company. But there is something wonderfully absurd about tattoos, I think, as I leave the hotel for ever changed. They are our attempts to freeze time, to make sense of ourselves, to tell people who we are. Whether or not I’m cool enough, I’m part of the club.