THE JOURNAL

Uninspired? Out of ideas? Stuck in a rut? Charge down the obstacles in the way of your next act of genius with our guide to developing and training your creative faculties.

Stop anyone in the street and ask them what sort of job they would really like to be doing. Lots of people will tell you that they’re happy working in insurance, pension planning and estate agency, but many others will tell you that they’d like a job where they get to be creative. If this strikes you as guess work, consider this from a recent article in The Guardian by the journalist Mr Simon Jenkins: “Britain now has 160,000 undergraduate and postgraduate students in ‘creative arts and design’, with more than 20,000 in drama alone. This is more than in the whole of engineering, or in maths and computing combined.”

What is driving this appetite for the creative life? Perhaps it is simply that, for thousands of people, modern employment means anonymity and conformity.

Those of us lucky enough to work in the arts, or the “creative industries”, then are apparently living the dream. But having to be creative all the time brings with it other problems, such as fatigue, or loss of ambition, or failures of self-confidence. How do you keep the flow going?

For some people – such as Messrs Pablo Picasso, or Bob Dylan – it is more likely to be a case of not being able to stop. In these exceptional individuals, the creative instinct is so strong it can’t be turned off. Most of us, though, need a bit of help. So, here are five ways of kick-starting a productive mind and, crucially, keeping the momentum going. Think of it as a shot of adrenaline for your creative faculties.

1. Look at things differently

There is a paradox at the heart of all artistic endeavours: we want to be original, but there’s no such thing as originality. If something was truly original, we wouldn’t be able to recognise it. “Originality” is created by combining existing elements in a previously untried way. Which means that the creative act is really an act of combination.

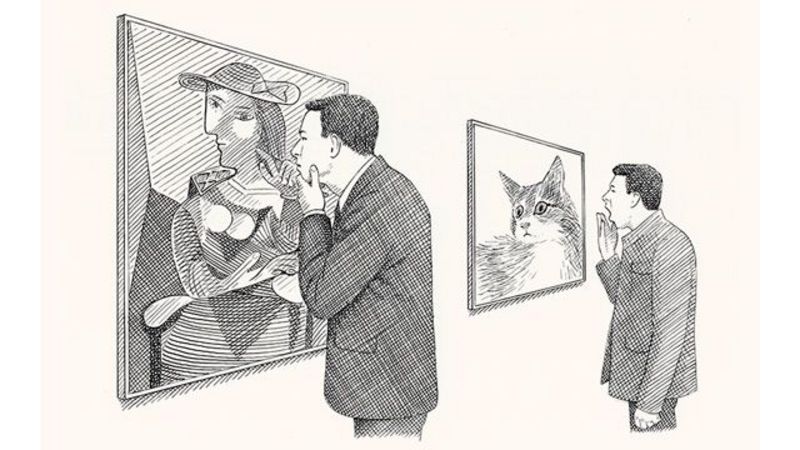

Take Mr Picasso. Most people, even his detractors, agree that he was a creative colossus. But what is it that makes him different from the person who paints kittens for greetings cards? Mr Picasso produced work that made people stare in amazement because of its sheer newness. This doesn’t happen when we look at the fluffy kittens on the “get well soon” card. We’ve seen fluffy kittens thousands of times before. And, at the risk of offending a very powerful constituency (fluffy kitten owners), they are a cliché.

Mr Picasso and the fluffy kitten painter are both creative because they both made things that didn’t previously exist. It’s just that Mr Picasso made his work by combining elements that had not been combined before (African tribal art, the classical tradition, impressionism, cubism – he even created art with headlines cut from newspapers). The kitten painter, on the other hand, is travelling down a well-worn path.

Musicians understand this idea of creative collaging better than most. Think of DJ Shadow: he makes entire albums out of other people’s tunes and sound fragments. But only musical curmudgeons and copyright lawyers would deny that he makes something fresh, new and exhilarating.

Getting started

Each week, make a plan to discover something new. It could be an author you’ve never read before, a genre of music you’ve never heard, a part of your home city you’ve never been to. You don’t have to like everything, but you should make sure you try it, and don’t be afraid of referencing anything that you do like for your own creative purposes. The wider and more eclectic your frame of reference, the more ideas you combine, and the more rich, weird and unique your creative output will be.

2. Take risks - embrace failure

Being a risk-taker is not easy. Our culture seeks to eliminate risk at all levels. As the British educational theorist Sir Kenneth Robinson notes, it begins in our education system: “All children start their school careers with sparkling imaginations, fertile minds, and a willingness to take risks with what they think.” Educators stamp out creativity by “criminalising” failure. Through the use of techniques such as standardised tests that have “single right answers”, children are encouraged to live in fear of giving the wrong answer. This is antithetical to the creative spirit, where the “wrong” answer is often the “right” answer. To achieve creative success we have to risk failure. There’s no other way.

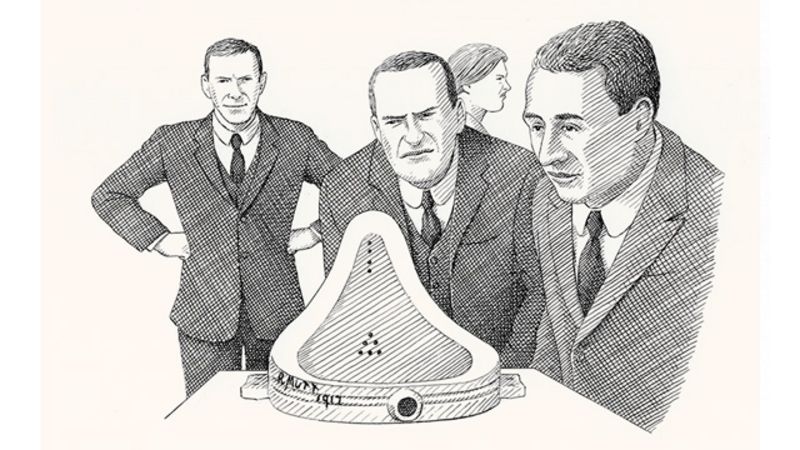

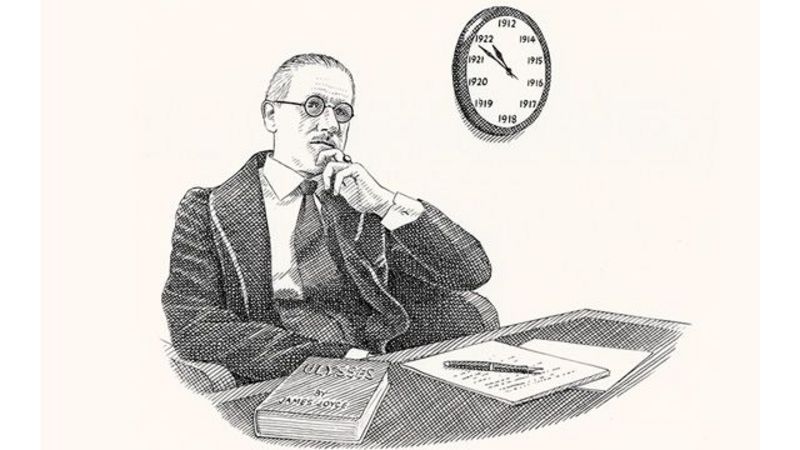

Think of Ms Tracey Emin’s “My Bed”, Mr Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain”, Mr James Joyce’s Ulysses. All of these works were met with derision and scorn. They were seen as examples of artists failing to adhere to the norms of the day. In the case of Ulysses, Mr Joyce risked everything – his sanity, his family, his friendships – to produce the greatest novel of the 20th century.

getting started

Set yourself some impossible, or difficult tasks. For example, drawing or writing with your left hand (if you’re left handed, use your right hand; if you’re ambidextrous, hold the pen in your mouth), or writing an album in a day, or a novel in a month (there’s an organisation, NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month), that sets aside November for this purpose every year). This almost certainly guarantees that you will fail in your attempt but, whatever you do, you must try your hardest. You may be surprised by the outcome, or it may suggest new ideas.

3. If it takes 10,000 hours, do the time

A creative person can produce a work of genius in a moment, but we can be sure that it was nurtured in the soil of hundreds of hours of slog. In his book Outliers: The Story of Success, Mr Malcolm Gladwell recommends 10,000 hours of effort and practice as necessary for success in any field – sport, business, politics, creative endeavour. He might be right. But he might even have underestimated the time it takes to produce a true masterpiece. Mr Joyce began Ulysses in 1914, but it wasn’t published until 1922 (although some of this time was spent in legal tussles, as he battled charges of obscenity). The Beatles performed countless Hamburg gigs before they made their first recordings in 1962. Half a decade later, when it came to the making of Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, they were in the studio for 700 hours before they, and Mr George Martin, were satisfied. Mr Jonathan Glazer spent nine years developing Under the Skin, his latest movie. Mr Brian Wilson took 38 years to finally release 2004’s Brian Wilson Presents Smile. Even if it means hours and hours of thankless labour, we have to be prepared to do the time.

getting started

Schedule time to be creative. Get up every day for a week at 5.00am and spend two or three hours working on that film script, play, poem, song or novel. If you’re a night owl, do the time at the end of the day, when you might normally be watching a late-night movie or pondering which box set to tuck into next. Depending on how you get to work, you can also turn your daily commute into a creative work session. Laptops and smartphones mean we can do many things on the move. If you catch yourself saying, “I’ll do it later”, you’re doing it wrong.

4. Think and act like an athlete

Top athletes train constantly. To stay in peak condition they can never stop training, and the tougher the training, the better the athlete. The same applies to creativity. The truly creative person never stops thinking and producing. There are no days off for anyone who wants to make great work.

Think about the famous “second album syndrome”. It’s a well-known phenomenon in music industry circles that a band’s second album often flops – especially if the band has had a successful first album. Why is this? There are many reasons, but we can be sure that a slackening of pace has something to do with it. First albums are often the products of long hours and endless practice. Bands work like demons. They practise every day. They play gigs. They write songs on the bus and in the breaks from boring jobs. But when it comes to producing a follow-up, creative muscles are found to have grown flabby. Bands think, “We’ve done it once, we can do it again, but this time we don’t have to work so hard.” Big mistake.

Unless we are prepared to go into the creative gym every day, and work, work, work, we will grow sluggish and run to fat. Everyone needs a creative fitness regimen. And for a creative individual, that means constant production.

getting started

Be your own personal trainer: set regular, measurable targets that work for you, and stick to them. For example, writing 500 words of fiction per week, doing a drawing every evening, or thinking of a new film concept each time you go jogging. This should help keep your mind permanently locked in creative mode. Joining a weekly class or group can help with this, and it doesn’t need to be expensive – search for community-run groups in your area via meetup.com.

5. Don't make excuses

There is one other major consideration we have to factor in if we are going to be creatively fertile. We can never blame others, or our circumstances, for our lack of creativity.

It starts from within and, while other people can disrupt its flow, only the individual can kill it. Some of the greatest works of art were made in conditions that most of us would consider totally non-conducive to creativity. In fact, in many cases, adversity, restrictions and censorship have even seemed to fuel creativity. Mr James Joyce was nearly blind when he wrote Ulysses, in chronic debt and troubled by enough personal demons to choke a horse. Yet out of this emerged his masterpiece.

The great blues artists of the first half of the 20th century grew up in grinding poverty and composed music with crude, homemade instruments. Yet one of the world’s great treasure troves of musical art emerged from these unlikely origins. So there can be no excuses. Start that novel today. Begin that screenplay on the train tomorrow. There really is no other way.

getting started

Every time you find a reason not to do something, write that reason down. Keep a diary of excuses for one week. Be honest. If you take a long train journey with the intention of working on your screenplay or writing the first chapter of the novel, but instead use the time to watch a movie, write that down. At the end of the week look back over the diary and you’ll be staggered to see how puny your excuses look. You’ll also see that the only barrier was you, and that, annoyingly, there is no one else to blame.

Mr Adrian Shaughnessy is a graphic designer, journalist and author of books, including How to Be a Graphic Designer Without Losing Your Soul and monographs on design legends Messrs Ken Garland, Henri Kay Henrion and Herb Lubalin. He is currently senior tutor in visual communication at London’s Royal College of Art and co-director of Unit Editions, an independent publishing house specialising in design and visual culture.

Think pieces

Illustrations by Mr Nick Hardcastle