THE JOURNAL

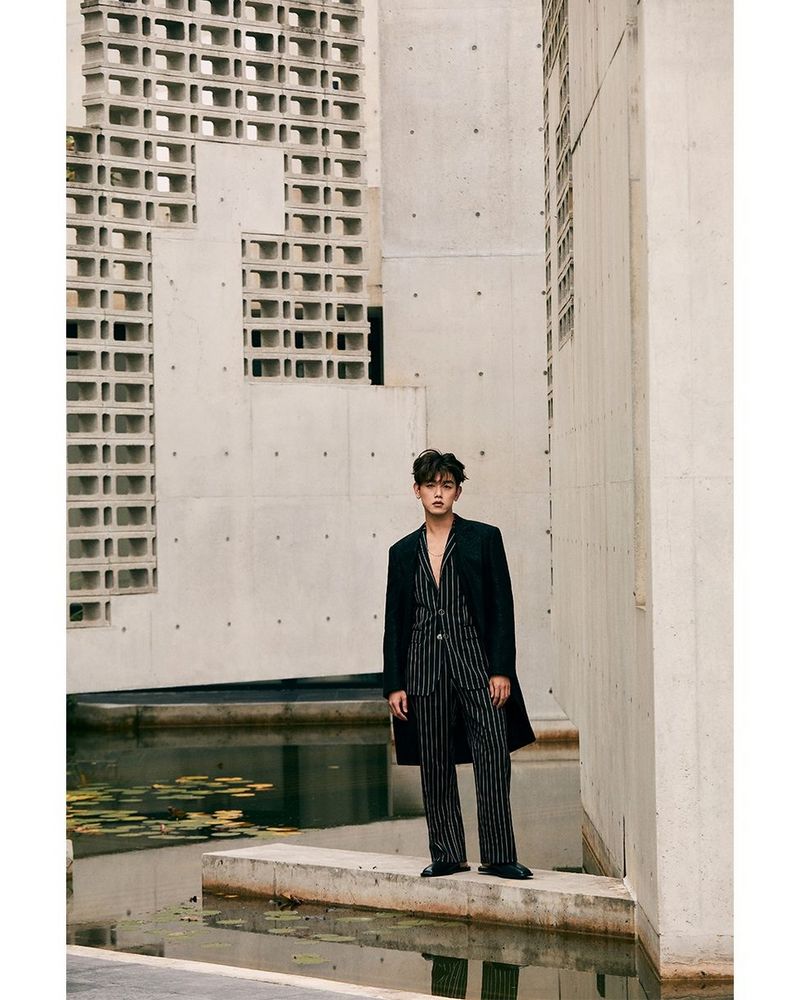

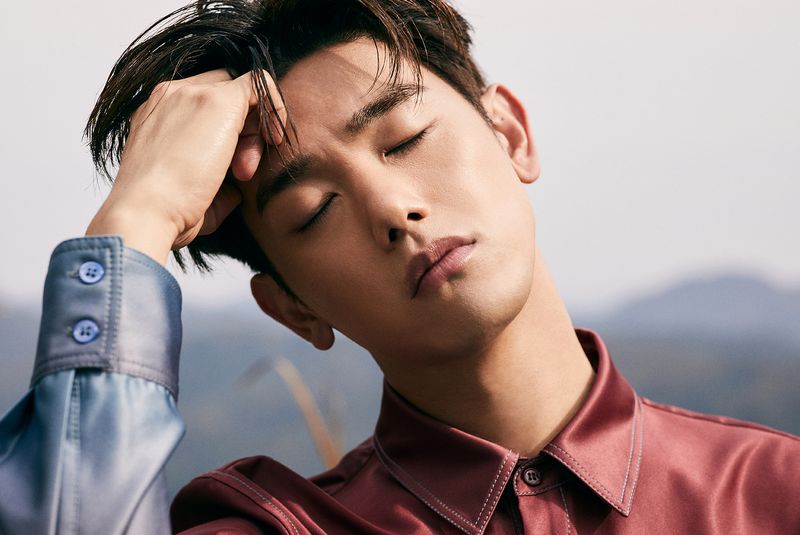

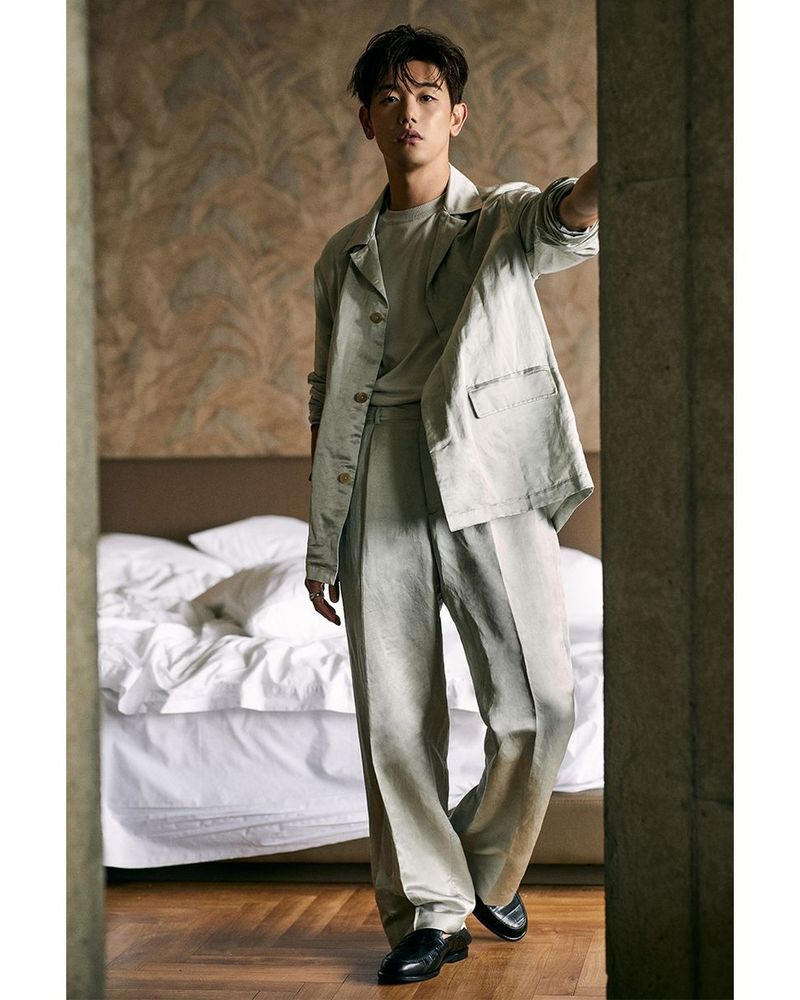

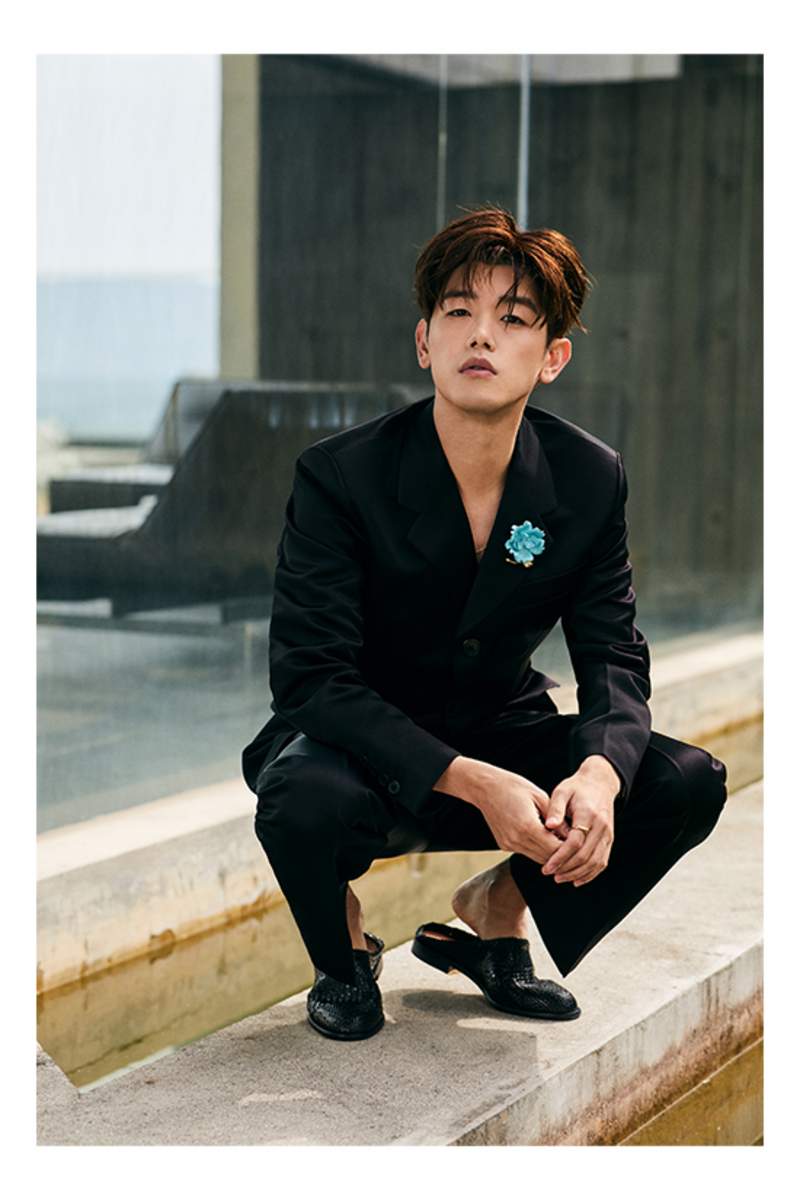

Mr Eric Nam is what you might call a frequent flyer. Indeed, it feels like we might need to invent a new term for the Korean-American singer, songwriter, TV host and businessman, because he seems to be everywhere, all the time. His MR PORTER shoot took place in Seoul, a city where he is known and loved as perhaps the most Western-leaning of K-pop’s current crop of stars. When we interview him a week later over the phone, he’s in Los Angeles, rattling off his 2019 itinerary.

“In June, we did a 12-date tour in Europe,” he says. “And then every month since August, I’ve been in the States twice a month. And then in the middle, I’ve been in Uganda, doing a fundraising charity show, then in Budapest to interview Will Smith.” It sounds gruelling, but Mr Nam is defiantly upbeat about it all, even when he comes to his concluding thought. “I’ve spent more time in an airplane than anywhere else,” he says, a tinge of amusement creeping into his voice. The implication being, well, shucks, what can you do about it?

In the K-pop industry, hard work comes with the territory. Korea’s so-called idols – poster-perfect triple-threat performers, recruited in their early teens – train for years and frequently work through the night to hone their pristine vocals and impossibly precise dance routines. Even within this context, Mr Nam doesn’t seem to be making it easy for himself. This year, as well as touring, he’s been working on his first English-language mini-album, Before We Begin, which was released on 14 November; he launched a weekly podcast, K-Pop Daebak, on which he discusses the latest K-pop releases; and began vlogging on his YouTube channel. And that’s just what he’s doing for the English-speaking world. In Korea, his schedule is even more jam-packed. “Because we’re in album promo mode,” he says, “there’s just so much content coming out. Even my fans are like, ‘Wait. How do we watch all this? And when did you have the time to make it?’”

Doesn’t he find all this the tiniest bit stressful? “It is stressful,” he concedes. “It’s overwhelming and exhausting. But when you’re in it, you’ve got to play the game, whether you like it or not.”

Mr Nam, to be fair, seems to have spent much of his life pushing himself to the limit and dealing with the consequences. Born in Atlanta, Georgia, to Korean immigrant parents, he was aware from an early age, he says, that he needed to work harder than his peers. “My parents’ English wasn’t that great,” he says. “So, for me to not be left behind in school and social situations, it was on me to go out and make things happen and meet people and make sure that I was included and understood properly.” This led to a youth where, he says, he was “stupidly over-active everywhere”.

Music was a part of this. He played the cello and piano, was in the Atlanta Boy Choir and, in his teens, started uploading cover versions of songs to YouTube. He was also involved in social work. He volunteered at homeless shelters, tutored migrant children in English and made annual volunteering trips to Latin America. In high school, he was elected student body vice-president. At Boston College, he continued in student government, participated in its fundraising activities and launched a local branch of the Asian-American cultural not-for-profit Kollaboration. Talk about overachieving. “My friends thought I was insane,” he says. “There was a point in my sophomore year that I was so stressed I thought I was going to pass out.” Nonetheless, all the frenetic activity paid off. By the time he was in his senior year at Boston College, he had completed an internship at Deloitte and had landed a post-graduation job there as a strategy and operations consultant.

So, in 2011, life looked set for Mr Nam. But then he had second thoughts. “I looked back at my college career and I realised I had done so much and gone through it so quickly that I was uncomfortable with going straight into work,” he says. “I guess the biggest thing was that I didn’t have the opportunity to pursue my biggest passions, which were social work and music. Both were very much discouraged by my parents. With social work, it was like, ‘Well, go make money first, then go help the people.’ And then with music, it was like, ‘That’s not a realistic option. Don’t even think about it.’ So, I promised myself I would take off for a year and pursue one or the other, if not both.”

This resolution led him to India, where he joined another social enterprise organisation. This, he says, spun him out a little. He was haemorrhaging money in India, with no sign that his work was having any impact. “For the first time ever, I was depressed,” he says. “Up until this point it felt like, when I put my mind to something, it tended to work out in some way. But now I was thinking I shouldn’t be here.” He considered going back to Deloitte, but was torn. Perhaps this was an experience he was simply supposed to endure. Then he got a message on YouTube in response to one of his cover videos.

“It was like, ‘Oh, we saw your video. Come to Korea. We’ll pay for your flight,’” he says. “It was the most spammy, scammy email I’d ever seen. It was like, ‘Please just send us your passport.’ I was so desperate that I did it. A few days later I got a ticket and was like, ‘Bye, guys. I’m going to go to Korea and pretend to live a pop-star life that I will never, ever have a chance to live again.’”

The sender of the message, it turned out, was MBC, a Korean broadcaster, which was looking for competitors for Star Audition, an X-Factor-style TV show on which contestants battle it out for the grand prize of a record contract (or the Korean equivalent, a “debut” launch by an entertainment company). This experience was less than serene. The show was filmed over nine months. When Mr Nam reached the final 20, he was moved with the other contestants to a communal house an hour and a half outside Seoul. He describes the atmosphere there as “cabin fever”.

This was the beginning of Mr Nam’s K-pop career. He finished in the top five, signed to entertainment company B2M as a solo artist in 2012 and, early the following year, released an EP, Cloud 9. During this period, he also landed two TV gigs, the first as the host of live-request music show After School Club, the second as an English-language interviewer for international celebrities. “I think having both of those and having to deal with the dichotomy of working between two completely different cultures and languages forced me to develop a TV and onscreen persona, which is what really catapulted my career,” he says.

“Working between two completely different cultures and languages forced me to develop an onscreen persona, which is what really catapulted my career”

Then there was the music. As an Asian man in Korea, Mr Nam was no longer the minority he had been in high school. He was, however, one of the few non-Korean-born, non-trainee artists in an industry where individuals are intensively coached from a young age and executives have fixed preconceptions about what a hit song sounds like. “Yeah, it was a lot,” he says. “To the point that I debuted and was on TV constantly, but it was like, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing’.” Where others had extensive training to draw on, Mr Nam had to refine his vocal skills by doing session work as a chorus and backing singer. It quickly became clear that the elaborate choreography that is a hallmark of idol groups such as BTS and EXO would not be a part of his act. “We quickly gave up on dancing because we were like, ‘This dude is not a dancer’,” he says laughing.

A further obstacle came in the form of his own musical taste. Raised on American top 40 pop, Mr Nam wanted to pursue a sound that was simple and upbeat, less bombastic and tricked out than your typical K-pop fare. His people were not convinced. “For years, it was like, ‘Eric, nobody listens to this,’” he says. In the end, deeply frustrated, he had to issue an ultimatum. “I do everything you guys want me to do on every level when it comes to TV and whatever, but music is the one thing I demand I have control over, or I’m just going to leave. I came here to do music and I have no intention of being unhappy doing music.” The label capitulated. His TV career was making money, so he was allowed to follow his own musical path, and did so, with 2016’s Interview and 2018’s Honestly, both hook-laden mini-albums co-written and produced with Korean and American artists. The difference that made his early career difficult, he says, is now what helps him to stand out.

Which brings us to 2019 and the next phase for Mr Nam: world domination. With Before We Begin, his first album fully in English, he is courting audiences outside Korea, particularly in the US and UK. The sound is suitably transpacific. There are chilled acoustic guitars that sound like Californian sunshine. There are woozy synths and EDM elements that nod to the sensibilities of Seoul. Both come together most happily in the album opener “Come Through”. The lead single, “Congratulations”, is an anthemic break-up song with a crowd-rousing chorus. The zingy “No Shame” is a perfect slice of Bieber-esque calypso pop. All in all, it’s a clear cross-over bid.

Despite his outsider status within the K-pop industrial complex, Mr Nam still thinks the US, the country where he was born, has more of a problem wrapping its head around him. “People always ask me why I chose to go to Korea to start my music career,” he says. “And I’m like, well I didn’t really choose to, but it was the only place where I wasn’t a foreigner, where I wasn’t other and where music industry people would take a chance on me. Even now, if you look around, there isn’t a single Asian face [in the US] that’s leading the charge. And that’s kind of crazy to me.”

He talks about representation in music a lot. The increased visibility of K-pop supergroups such as BTS and Blackpink in the West is definitely a good thing, he says, but it’s merely the first step. More important is the idea that young Asians, wherever they may have been born, have access to a dream that, as a minority in the US, he felt he was denied in his home country. “Even if I don’t become the next Justin Bieber or Justin Timberlake or Sam Smith,” he says, “that’s fine, because I feel like I’m encouraging a cultural shift that I hope to see happen in the next five, 10, 15 years. Like some 13-year-old kid sees me and thinks, there’s an Asian face. I’m Asian. I could try to do that, and it’s not weird.”

“I still don’t know how I’m doing this. It’s a ridiculous life, but it’s about letting yourself feel things”

To get to this point, he’ll have to survive his own frenetic schedule. He says he’s been offered acting work, but turned it down. “I can’t add one more thing,” he says. “I would die. I still don’t know how I’m doing this. It’s a ridiculous life, but it’s about letting yourself feel things and letting yourself be OK with how you feel at certain moments throughout the day. That mentality has definitely helped me and that’s definitely taken a lot of pressure off my shoulders.”

The pressure of stardom is a hot topic in K-pop at the moment. This week, the actor and former Surprise U member Mr Cha In-Ha was found dead at his home. The details of how and why have not been confirmed, but the incident follows the suspected suicide, in November, of singer Ms Goo Hara six months after she was hospitalised following a rumoured earlier attempt to take her own life and, in October, that of her friend and former bandmate, the outspoken singer Sulli, who, before she died, had openly discussed her mental health struggles. Both Ms Hara and Sulli were victims of relentless and misogynistic trolling for falling short of the squeaky-clean image that is expected of every K-pop idol.

And these are not the only deaths to have rocked the industry in recent years. One further high-profile case is that of the boy group Shinee’s lead singer, Jonghyun, who took his own life in 2017 at the height of his fame, citing unbearable feelings of depression and self-loathing. So much tragedy has caused many to criticise the punishing conditions of the K-pop trainee system and the impossibly high moral standards that its stars have to maintain in public. There is also, clearly, a stigma around mental health that persists in the country.

Mr Nam is adamant that his huge social media presence causes him no anxiety and that, despite the hectic schedule, he is positive and happy, but he has certainly come up against the rigid standards of the K-pop machine. “I was going through a difficult time when I first got to Korea because my company and I just didn’t get along,” he says. “I was told I was going to be able to make music and then I wasn’t able to, and it was a big identity crisis. I got really upset. I thought I was going crazy, so I thought I should go and see a doctor. But even then, they were like, ‘No, no, that’s not talked about. That’s not healthy.’ I still remember that all being very hush-hush. ‘We’re going to take you to this doctor far away and no one will know you’re there.’ I was like, ‘Is this necessary?’”

According to Mr Nam, Korea is an open, vocal culture and its idols support each other, but he says there is still much to be done in terms of opening up discussions around mental health. “I think there is still an issue, unfortunately,” he says. “These tragic things happen and it’s something that really should start a dialogue, but I don’t think it has yet. And that’s disconcerting to me. I want there to be a larger dialogue and I want there to be more resources and I want people to be able to talk about it. I think only time will tell, but it’s through interviews like this where I or other people can say, ‘I’ve been through it, I’ve found ways and means to deal with things,’ and be open and expressive about it that I hope really pushes the envelope forward and kind of takes the stigma away from it.”

After more than an hour’s conversation, during which he barely pauses to draw breath, you have to wonder if he ever relaxes. “That’s one thing I’m working on that I’m really bad at,” he says. “I have trouble disconnecting. But if I were able to do it, I would spend a week in the mountains or a resort and just read and sleep and eat French fries.” In the same breath, he describes his career as a “startup”, one that requires passion, drive and a huge amount of work. Given the way in which he is always expanding into new channels, new media, new markets, it’s not a bad comparison.

“I’m going to keep moving and make all these things happen, and be the first on everything, and try to do things differently from everyone else,” he says, explaining the expanding nature of his media empire. And you can tell he means it, not least because, as we approach the end of 2019, he’s showing no signs of slowing down. There is, he says, another full-length album in the works – Before We Begin derives its name simply from the fact that it’s a precursor to bigger things. In March, there will also be more touring, which means, yes, another punishing itinerary. “If everything goes to plan, we’ll have hit about 40 cities in the US and Latin America,” he says, no less energetic than when we started talking. “I’m probably the most expansively touring K-pop artist in the world right now, in terms of cities and dates.” Other men might describe this prospect as “challenging”, perhaps, or even “daunting”. For Mr Nam, though, it’s only one thing: “reassuring”.

Before We Begin is out now