THE JOURNAL

Why Balenciaga’s Triple S Sneaker Is A Work Of Art.

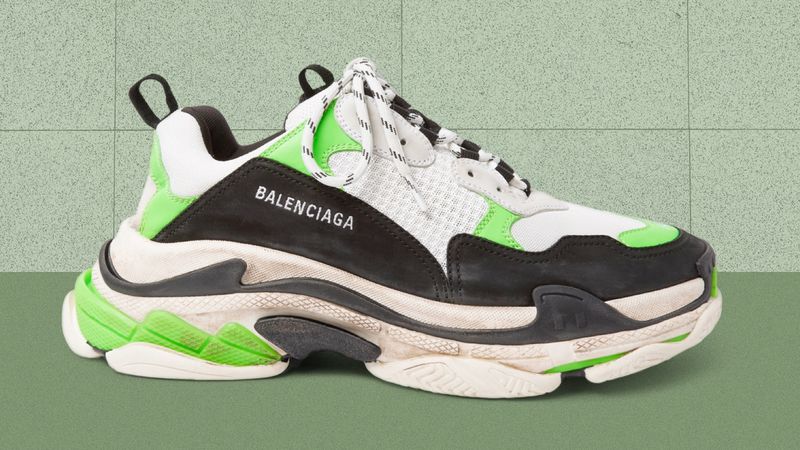

Since making its runway debut a year ago, and going on sale, and selling out, for the first time last autumn, the Balenciaga Triple S sneaker has been called “ugly,” in The Wall Street Journal, “a chunky, bulky, overdone take on a dad sneaker” by GQ and “homely clompers” by The New York Times. It’s all perfect praise for the label’s creative director Mr Demna Gvasalia, who told once Vogue he considers it a complement when people throw shade. Pushing boundaries, he feels, is part of his job; ugliness may be the righteous path.

The first time I saw the Triple S in the flesh, however, compelled me to evaluate it in a different context than whether its beautiful or not. I was at an awards ceremony in November for WSJ. Magazine. Mr Marc Jacobs had a pair on his feet, the green-yellow-black colourway. Above the ankles, he wore a black suit with a black tie. More importantly than the cred he conferred with his footwear choice, was our location. We were all at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan, which put the obsessed-over-yet-derided shoe in the same building with so many other works that polarise.

While a line can be drawn between the Triple S and other sneakers with swollen soles and exaggerated geometry out around the toe and beneath the heel – the New Balance 991, the Nike Air Max 90, the Asics Gel Lyte 3, Reebok’s InstaPump Fury, Raf Simons’ adidas Ozweego and nearly every piece of sneaker-esque footwear ever designed by Messrs Yohji Yamamoto and Rick Owens – the Triple S also makes sense amid the art; sculpture, in particular.

As an object, it conveys strength through its structure and whimsy through its colour blocking and shapes. In that way, it brings to mind Mr Jeff Koons’s 2014 “Play-Doh”, a monumental work of burstlingly-bright slabs, piled, sloping and cracked in places (the Triple S is also weathered to imply use) that the artist needed 20 years to make. And would it be so much of a stretch to imagine the late sculptor Mr John Chamberlain in a pair of Triple Ss, assembling his iconic metal marvels while wearing a shoe that, like his own work, weaves together industry with elegance? In 1963, Mr Claes Oldenburg produced a muslin, plaster, wire and painted enamel work called “Giant Gym Shoes”. That may have been the first ever sneaker to attempt wit: an everyday object, Mr Oldenburg was saying, could also be a work of art.

Perhaps Mr Gvasalia’s is saying that, too. With his asserted interest in challenging the nature of beauty itself, he’s provoking – and daring to be misunderstood – in a way that’s less common in fashion than it is in the art world. And it’s worked. What a hyped shoe must be above everything else, after all, is talked-about. Not everyone is looking for provocations on their feet, but for those who are, the Triple S matches the feeling of the moment we’re living in: it over-communicates and prefers size to subtlety, but, also, it proves to be far more complex than it seems to be at first glance. “I think the Triple S is representative of a Dadaism period we’re going through,” says designer and sneaker world heavyweight Mr Jeff Staple. “It’s fun. It’s irreverent. And it’s an anomaly in the grand scheme of the culture as whole.” That deviation will also make it a prime re-release in about a decade – when 2017 and 2018 somehow generate a feeling of warm nostalgia. In the mean time, though, if you want a pair, move fast before they’re gone – again.

Mr Howie Khan is the co-author of New York Times bestselling book Sneakers (Razorbill). Get it here.

Get your kicks