THE JOURNAL

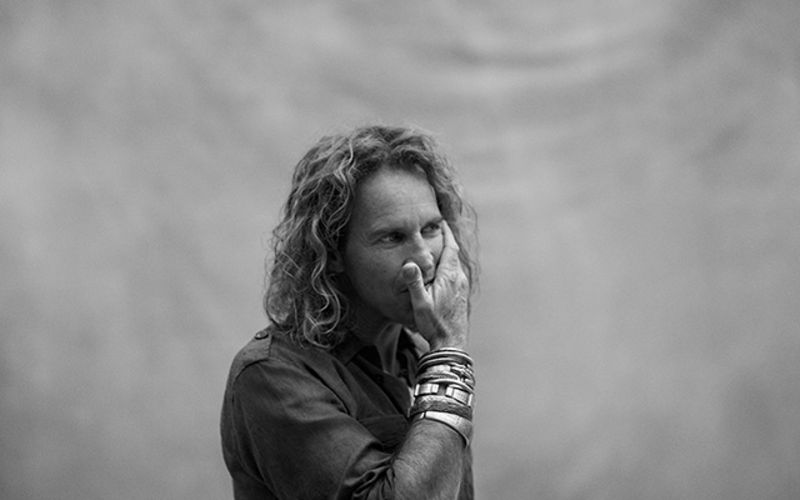

Mr Ralph Bousfield, safari guide to the A list, on Kalahari life and the importance of moleskin.

Mr Ralph Bousfield belongs to a vanishing species of African guide. He was born to a great white hunter and raised in the bush, giving him the depth of knowledge to command one of the highest day rates in the game. His client list includes former US president Mr George W Bush, film-maker Mr Joel Coen and the actress Ms Frances McDormand, with trips ranging from the Danakil Depression in Ethiopia to the depths of the Congo. I meet him in the more elegant locale of a private riad in Marrakech.

We are at a party and it’s after midnight. Mr Bousfield asks if I can bring him back a shrunken head from Papua New Guinea. “I need a shrunken head,” he says, to add to his collection of human skulls, spears, lip plugs, earplugs, fertility medicines, bird skins and “bits and bobs of family members, all in bottles”. Mr Bousfield keeps these curios in his cabinet-packed office in Francistown, Botswana. “You’d love it there, it’s full of generations of collecting,” he says. Mr Bousfield then tells me about his bracelets. His sun-crackled wrists jangle with them: leather, twisted copper and thick silver cuffs, some of them carved with shamanistic symbols.

“They are all for protection,” he says, pulling the hair back from his face, which is a knot of long, sun-torched curls. “This one has the footprint of the jackal and this one has the chameleon’s eyes to see trouble coming.” Some are early explorer trading goods from Angola, Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria, the Sahara and Cameroon, which are all countries Mr Bousfield has travelled in the course of his work.

In such a line of work, it is unsurprising Mr Bousfield treasures talismans. He also wears them around his neck, in an antelope’s scrotum. Inside are beads and stones given to him by shamans, as well as a talisman from his friend and mentor, the American photographer Mr Peter Beard, a close friend for 25 years, who knew Mr Bousfield’s uncle and father. Most valuable of all is the snake stone, which is black, like onyx. “If anyone gets bitten I make an incision and use the stone to draw out the poison,” says Mr Bousfield. “My father never went anywhere without it. He wore it around his waist in a pouch – the same pouch I held on to in order to pull him out of the plane crash.”

“I like the way things look, but in the bush, style has to follow substance”

Mr Bousfield’s father, Jack, was a professional white hunter and the fourth generation of the family to live in Africa. He hunted 53,000 crocodiles in his 69-year lifetime, got gored by an elephant with a tusk through his lungs and survived sleeping sickness. Mr Bousfield’s mother’s side arrived in Africa in the 1670s. In the late 19th century, his great-grandfather, Major Richard Granville Nicholson, was chosen to escort Princess Eugenie to the site of her son’s grave after the Anglo-Zulu War.

This long history – and familiarity with the dangers of travelling this tricky territory – wasn’t enough to save Mr Bousfield’s father when, on 30 January 1992, father and son were flying over Botswana’s Okavango Delta and the plane came down. It was his father’s seventh crash, and the one that killed him. There is sadness, but also disbelief in Mr Bousfield’s telling of the story: he pulled his father from the burning plane, in the course of which 45 per cent of his own body was crisped to the bone. “I had to stand on the wing tanks to get him out,” he says. “My feet got completely cooked.”

Hence the reasoning behind the rest of his outfit. He wears a tailored khaki cotton moleskin bush jacket – the only material that’s soft enough on his burnt skin – that works just as well in Botswana’s Kalahari as it does in the Marrakech nightclubs, where he later goes out dancing until 3am. “I like the way things look, but in the bush, style has to follow substance. The thick moleskin won’t get caught on thorns. Same with boots. I always wear brogue ankle boots. They’re tough, with hand-stitched saddle leather,” he says. So admired are these signature pieces, Mr Bousfield now sells the jacket under his Hickman & Bousfield label, an online safari outfitter launched with his girlfriend, Ms Caroline Hickman, in summer 2013. As for the boots, London shoemaker Ms Penelope Chilvers has just launched the Bousfield boot – styled after father and son.

“Lose wonder, and a part of you dies”

Mr Bousfield, the last child of five from his father’s two marriages, is a chip off the old block. He too is a pilot. “I’m on my fifth crash,” he says: “I’m very good at crashing. If you’re going to crash, you need to be with someone who knows how to crash.” He is also a master tracker and a trained biologist, able to talk Latin nomenclature as easily as he can the clacking language of the Kalahari bushmen with whom he was raised, his schoolboy education later propped by a few years in prep school in Botswana and a private school in South Africa. “The shamans are also a big part of what I like and do. If I could, I’d do trance once a week,” he says, describing the ritualistic chants and dancing that make up these occasions. “I guess I like to slip between different worlds,” he says, meaning not just the spiritual and material, but Montauk, where he visits Mr Beard; Notting Hill, where he has a house; and the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans, where he has three of his four safari camps. His special subject is the wattled crane “as an indicator species of wetland destruction”, which he studied at the International Crane Foundation in Wisconsin under his other significant mentor, Mr George Archibald.

It is one of those birds Mr Bousfield is now describing in the warm Marrakech night, how he’d gone to the former private museum of Mr Lionel Walter, 2nd Baron Rothschild, at Tring in Hampshire, England, to find wattled crane “study skins”. He got talking with the curator. “He pulled birds out and handed them to me,” says Mr Bousfield: “They had pencil-written labels attached to them. Then I noticed what it was I was holding: Darwin’s Galapagos finches on which he based the theory of evolution. I had the origin of species in my arms – the actual birds.”

As he tells this tale, the wonder is electric. It is the same sense of awe Mr Bousfield communicates on safari. “Lose wonder, and a part of you dies,” he says. I ask if that’s what really motivates him, or is it fear that provides the bigger rush? “No – it’s not that. When I think of the place I feel most content, it is when I’m alone in the Kalahari. This is the least changed landscape from the time our species came into being. There is resonance in the ground. I’ve always liked places that are wild and dark, but most of all I like the places that have stood still forever. It is where I live my life and feel completely at peace.”

Mr Bousfield’s guiding services in Africa (from $2,550 a day) can be booked through his safari company, Uncharted Africa. Mr Bousfield also owns and operates four luxury safari camps in Botswana: Jack’s Camp, San Camp, Planet Baobab and Camp Kalahari, plus a mobile safari unit. He is talking at London’s Royal Geographical Society on 14 January.

Mr Bousfield’s top five safari spots

Danakil Depression, Ethiopia “This is where I took George W [Bush] – a properly extreme environment. It’s pre-oxygen on earth, with volcanoes 400ft below sea level.”

Zakouma National Park, Chad “Zakouma has only recently opened up and has huge poaching issues. But this is a destination on the turn – and has flocks of more than 5,000 black crown cranes.”

The Kalahari, Botswana “This is where my soul is invested – with one of the world’s oldest cultures who have been living there for at least 35,000 years, maybe as long as 75,000.”

Niassa Reserve, northern Mozambique “Niassa is a huge unexplored, undocumented wilderness that has stood still because of the political situation, now more-or-less resolved.”

Skeleton Coast, Angola “Nearly everyone does the Skeleton Coast in Namibia. The other side of the border, over the Kunene River in Angola, is even more exciting.”