THE JOURNAL

I’m a British South Asian and – shock horror – I’m not a doctor. I’m not a lawyer, either. Or an accountant. Or any of the other professions my aunties would be keen on. OK, so I’m poking fun at the stereotypes here; actually, I applaud the South Asians who are rocking those professions. Some are even in my family. But as a writer and that rare bird – a person of colour working in the creative industries in the West – I believe in championing the South Asian kids who went the other way. The ones who got told by their parents to get “a proper job”, but persisted in careers in the arts because they had a passion and something to say.

The South Asian talents in this portfolio are just such folk. We invited them to showcase the spring/summer 2023 collection by Stone Island – a brand that, more than most, has been a marker of community and badge of identity since its inception. These creative souls are blazing trails, exploring heritage and existing in spaces where brown people are typically underrepresented. I, for one, salute them.

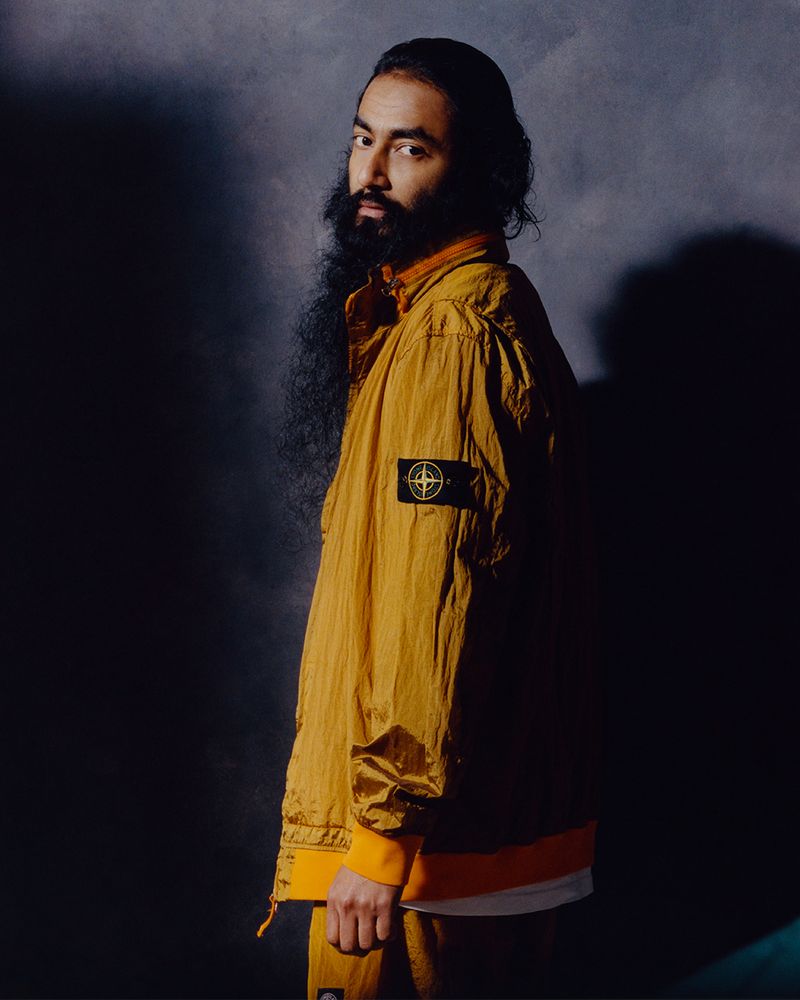

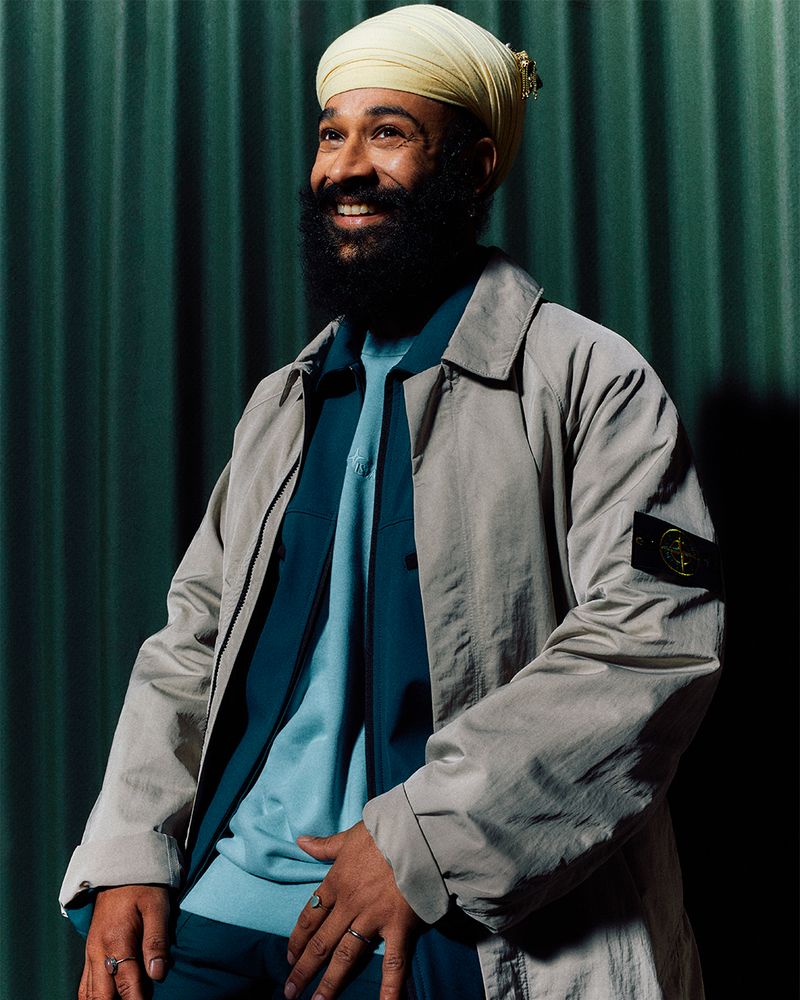

Messrs Jatinder Singh Durhailay and Suren Seneviratne, musicians

Mr Suren Seneviratne, 36, is a Sri Lankan-born, London-based experimental musician who performs under the name My Panda Shall Fly. Mr Jatinder Singh Durhailay, 35, is an Indian classical musician from London who plays string instruments the dilruba and taus. Together, they’re known as Petit Oiseau and create music that fuses classical sounds with ambient synch effects made using an EMU-XL workstation.

Their output is an expression of their South Asian identities, says Durhailay, but also their London sensibilities. “We grew up [having] a multicultural dialogue with lots of different groups of people,” he says. “This [collaboration] is another branching out.”

Seneviratne’s music as a solo artist has largely been informed by the bass-driven club-culture sounds he grew up with in south London. Working with Durhailay has been a sort of reconnection to his roots. “Petit Oiseau is this very explicit celebration of South Asian identity and everything that is possible within it,” he says. “For me, it’s been moving falling in love with that again.”

Among various side hustles, Durhailay is also a painter whose work references Indian miniature painting and celebrates ideas of “openness and inclusivity” that blossomed under Maharaja Ranjit Singh. “There is so much beauty within Sikh culture I want to share,” he says.

Seneviratne has his own following as a model who has featured in numerous campaigns. “Being able to represent when there is such a lack of South Asian representation has become the most important thing for me,” he says.

“His impact on Asian youth, especially Punjabis and people who keep their facial hair, is huge,” Durhailay adds. “People have become confident about their culture and looks. That’s the power of a photograph. Even I see myself in him. He’s a hero.”

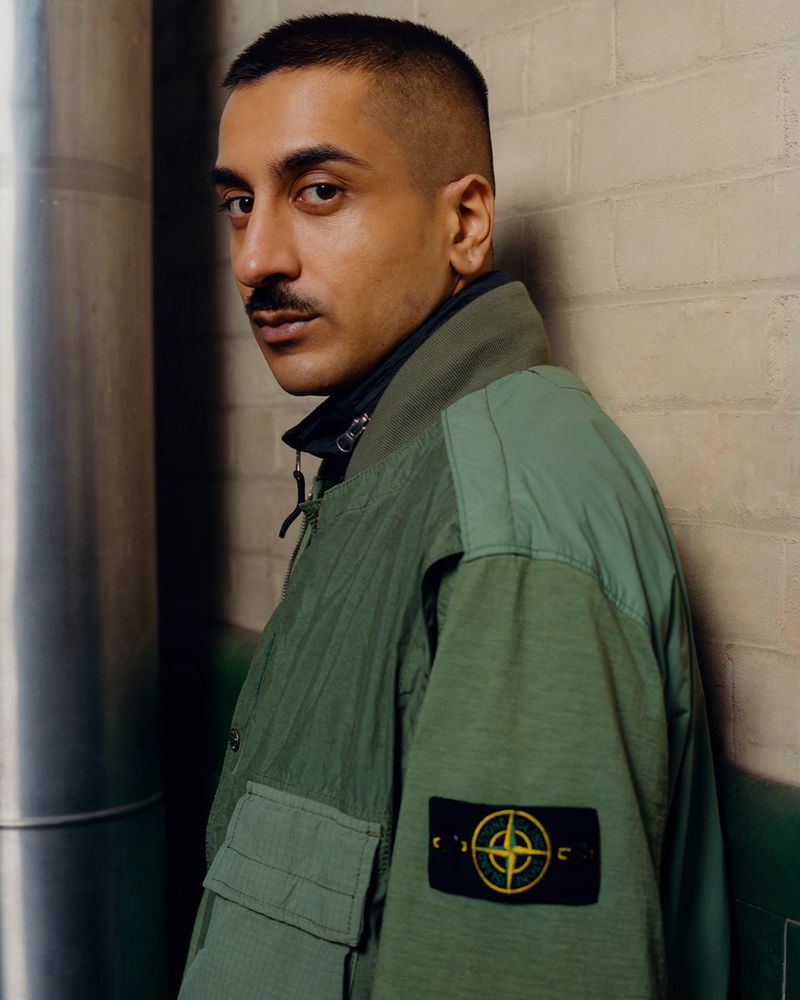

Mr TJ Sidhu, writer

Stone Island Nylon, Cotton And Supro Hooded Jacket and Nylon And Cotton Utility Trouser coming soon

“I wanted to work at a magazine from the age of 10,” says Mr TJ Sidhu, now a junior editor at style bible The Face. He remembers begging his mother to buy him a copy of Q magazine, which he read cover to cover and scrawled comments on with a sharpie pen. “I was an editor-in-chief in my bedroom in Reading,” he laughs.

Now 27, the Central Saint Martins graduate covers mainly emerging talent in fashion, art and photography. Sometimes his pieces reflect his British Indian heritage, such as a report on British Asian footballers and lack of representation on the pitch. More often they speak to his interests as a gay man navigating queer culture and gay nightlife in London.

Stone Island Nylon, Cotton And Supro Hooded Jacket coming soon

“I never thought of my skin colour as an obstacle. But I definitely feel a responsibility to question diversity,” he says of the UK media where British Asians make up just 2.5 per cent of the journalist population. “As a kid, I used to study the masthead of magazines. And what’s special within the Indian and Pakistani community is our names are such signifiers of where we come from. If I saw Sidhu on the masthead, I would be like ‘Great, a Punjabi boy at that magazine’.” That 10-year-old would-be editor with a Sharpie would approve.

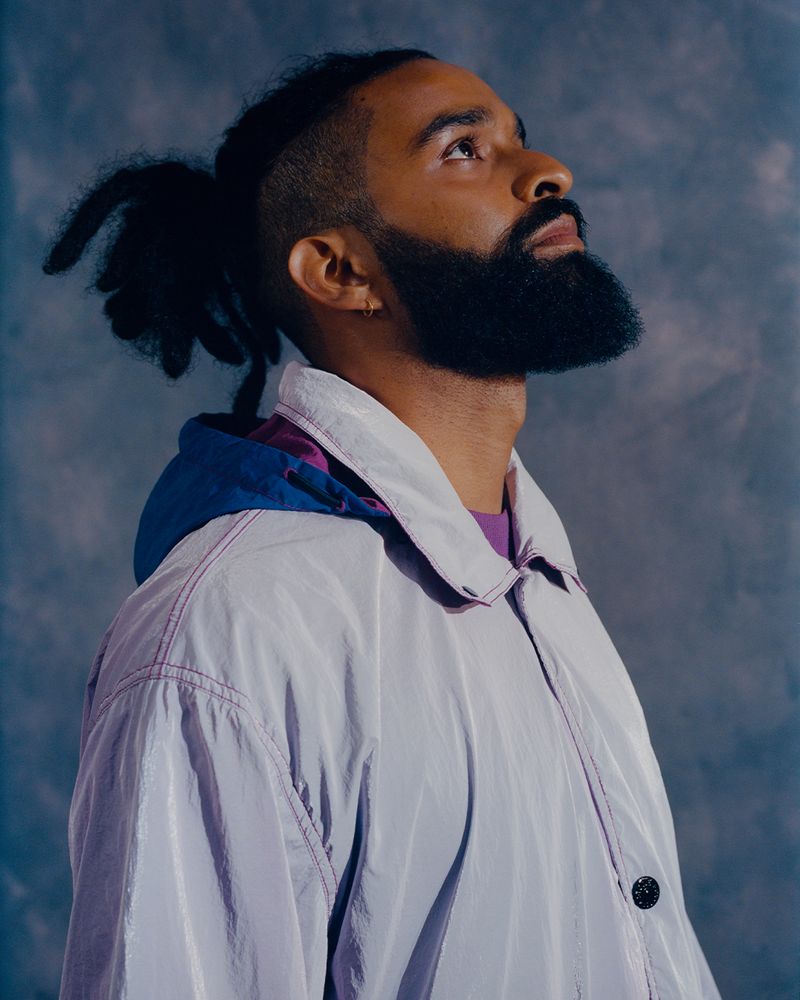

Mr Rory Bentley, filmmaker

Stone Island Hooded Fishtail Parka In Cotton-Cupro Weave coming soon

Stone Island Hooded Fishtail Parka In Cotton-Cupro Weave coming soon

Mr Rory Bentley grew up in Leicester the son of a Punjabi Sikh father and Welsh Caucasian mother. After his father’s death, his mother moved him and his sister to Edinburgh. Bentley went from being surrounded by Sikh relatives and at a school where “everyone was either a Patel or Singh” to a place where being brown put him in the minority and ties to his Punjabi family were all but cut.

Going by the name Rory Bentley instead of his birth name Ranjit Singh Dhariwal, he found himself “erasing” his brown roots, in part to numb the pain that came with remembering. “Every time I saw a turbaned man, I thought it might be my dad,” he says. “So, I hid [my Punjabi identity]. I repressed it and didn’t tell anyone I was Indian.”

Now an award-winning writer-director, Bentley, 30, is drawing on his early years to make his debut feature Amrit, which he describes as “Asian Moonlight meets Ratcatcher” and starts shooting this year. “One of the key issues in the film is how you grow up perceiving yourself as not fitting into either culture you were born into and the tailspin that you can send you into when you lose one parent,” Bentley says.

“I was scared to tell this story because I knew it would require plumbing a grief I’d kept suppressed for a long time,” he adds. “But making Amrit has allowed me to remember who I am. I don’t want to be seen as just a mixed Indian filmmaker. But it’s important to create these stories [of mixed-race identity] to allow others to tell their own.”

Mr Dhruva Balram, writer, editor and producer

Stone Island Marina Hooded Light Nylon Water- And Wind-Resistant Jacket and Marina Capsule Garment-Dyed Cotton T-shirt coming soon

Stone Island Marina Hooded Light Nylon Water- And Wind-Resistant Jacket and Marina Capsule Garment-Dyed Cotton T-shirt coming soon

Mr Dhruva Balram was born in New Delhi, moved to Toronto aged 12 and has lived in London for the past five years. In 2015, however, he was back in India and working as an editor at the alternative culture platform The Wild City. The wealth of local artists featured on its pages convinced him of one thing – how consistently the global media fails to shine a spotlight on South Asian talent.

When Balram moved to London, he hoped to redress that. He began writing about South Asian artists for publications such as Mixmag. Then the pandemic hit, opportunities for freelance writers dried up, and he had to devise new ways to spotlight his peers. In 2020, he launched Chalo, a non-for-profit organisation whose first project, a 28-track compilation featuring artists like Ahadadream and Ms Nabihah Iqbal, was named one of The Guardian’s top 10 albums of the year. In 2021, he co-founded Dialled In, a festival dedicated exclusively to South Asian artists. All three editions have sold out with a new iteration planned for later this year.

“We created a space for a lot of [artists],” says Balram, 31, of the festival’s impact. “And it allowed people in the Global North to understand the variety of South Asian creativity. It wasn’t just Bhangra or Bollywood. It was everything from slow jazz to punk rock to sugary pop.”

A highlight from last April’s edition is a case in point: “I was standing on the main stage where Anoushka Shankar was playing the sitar like an electric guitar. It was almost ethereal. Then I went downstairs to the basement and there were a thousand people raving to drum and bass and fucked off their tits.” Here was a celebration of diverse tastes within the South Asian community that was, he says “long overdue”.

Ms Tami Aftab, photographer, and Mr Tony Aftab, chef

Ms Tami Aftab, 25, began documenting the experiences of her Pakistani-born father Mr Tony Aftab five years ago. She was studying for a BA in photography at London College of Communication and keen to explore the impact his unique form of short-term memory loss had on his life.

What struck her most about that early footage, however, was not the sadness around his condition but her father’s chipper sense of humour in dealing with it. It was the starting point for an ongoing series of “performative and humorous” portraits taken in collaboration with her father called “The Dog’s In The Car”. The title was inspired by the Post-It notes stuck up around the house for Tony – in this case to remind him where he might have left the dog on returning from his walk.

Stone Island White Grime Sneakers coming soon

“There’s a fine line between humour and mockery,” Tami says of her pictures which turn the negativity often associated with illness on its head. “That’s where our collaboration is important. After discussing what kind of images we’re going to take, the way Dad executes them just makes them humorous.” One wry set-up shows him wearing several hats piled up on his head – a nod to his habit of buying new ones when he forgets he already owns plenty.

Alongside a day job in retail, Tony runs Serfraz Kitchen, a London-based pop-up kitchen serving Pakistani home cooking. Having lived in the UK for 30 years, he believes these portraits reflect both his and Tami’s very British sense of humour. Relatives in Pakistani don’t get the joke, notes Tami. Collaborating on this project has also strengthened their bond as father and daughter. “Working together brings more love,” Tony says. “I feel very proud.”