THE JOURNAL

The doodle Mr Samuel L Jackson has created is well-composed but, without a tour of its features from the artist, abstract. The drawing is for Ms Autumn Moultrie, a make-up artist who has been working with Jackson for a decade. Every year, the Los Angeles school that Moultrie’s daughter attends auctions off these doodles, gathered from celebrities by connected parents, to support its financial aid programme – Los Angeles’ answer to the traditional bake sale.

Moultrie removes the sheet of paper from between two pieces of cardboard and holds it up in front of Jackson, who explains. On the upper left, he has drawn the eye patch he wears when he plays Nick Fury, his Marvel alter ego. The other component, on the lower right, is not so easily deciphered. Moultrie says it looks like a bikini. It is a geometric rendering of Nick Fury’s goatee. The two elements are made up of hundreds of tiny Xs in black ink.

“Maybe it needs…” Moultrie starts gently, studying the drawing.

“I didn’t do enough hair? Is that it? I didn’t make it thick enough? I didn’t want to make it thick, because I wanted it to be Xs,” Jackson says. He says the last doodle he did for the school’s auction was a pointillist self-portrait. It is moving to contemplate Jackson hunched over a piece of paper, carefully drawing Xs and dots in the service of Moultrie’s daughter’s school.

“I think, with the eye patch, the scale is a little off,” Moultrie says.

“The scale is off how?” Jackson says, sounding offended. “I wasn’t trying to make it a face, number one. I was just trying to make the objects. I mean, I can put some more Xs in it, if you want.”

“We’ll see,” Moultrie says. “If you still have the pen, we’ll talk about it.”

Moultrie carefully slides the drawing back into its cardboard protector. She wears a bright red sweater with bell sleeves that she deftly keeps out of the way as she takes up her tools and goes to work on Jackson’s face. He is reclining in a tall white leather chair with his feet over the armrest of another chair.

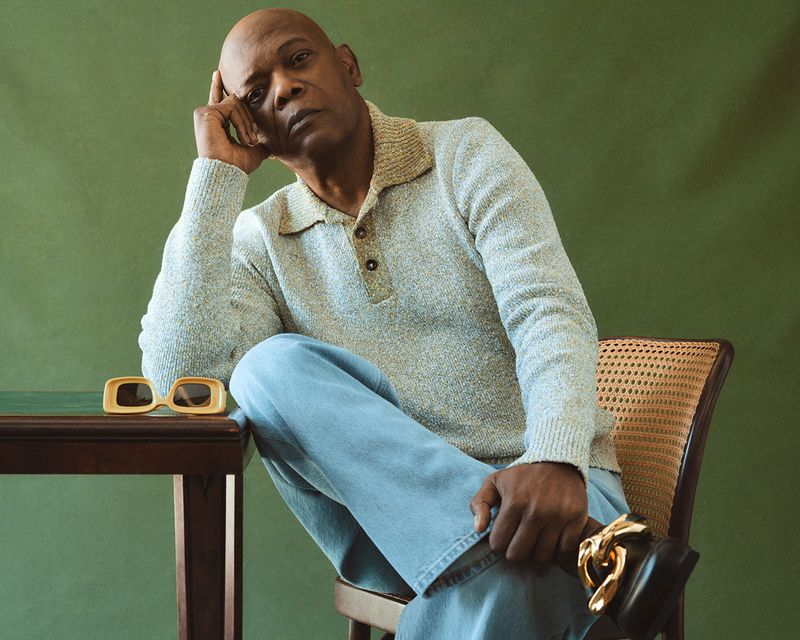

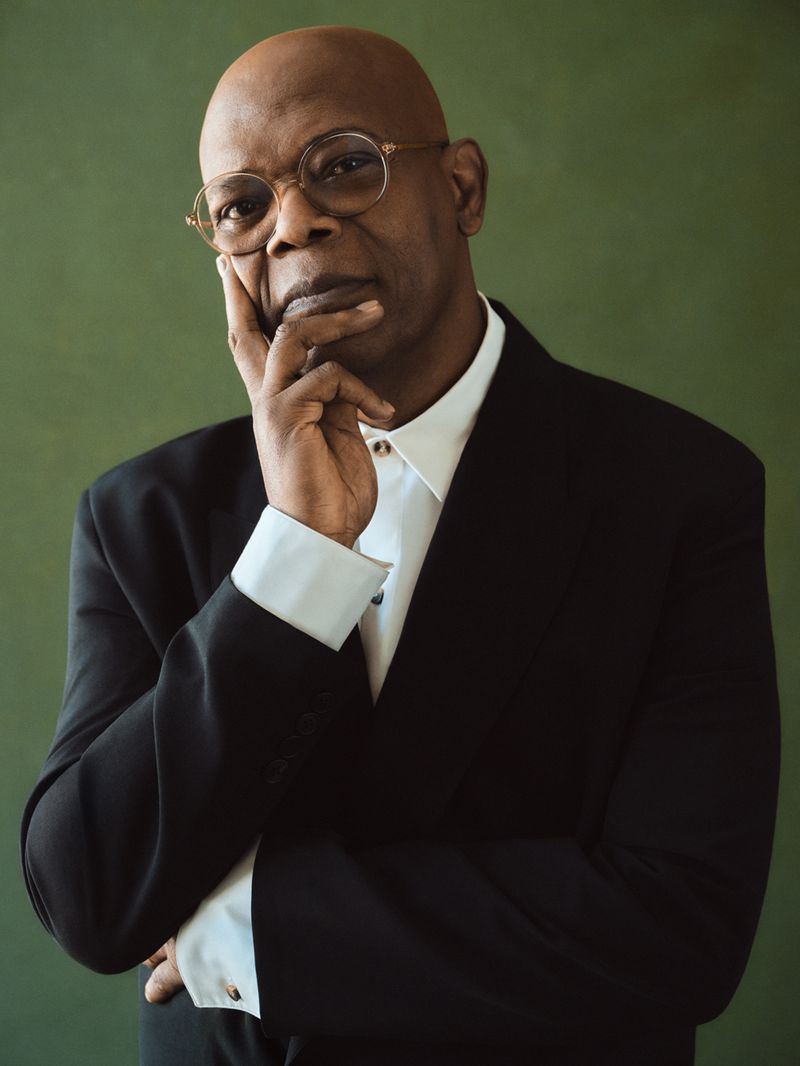

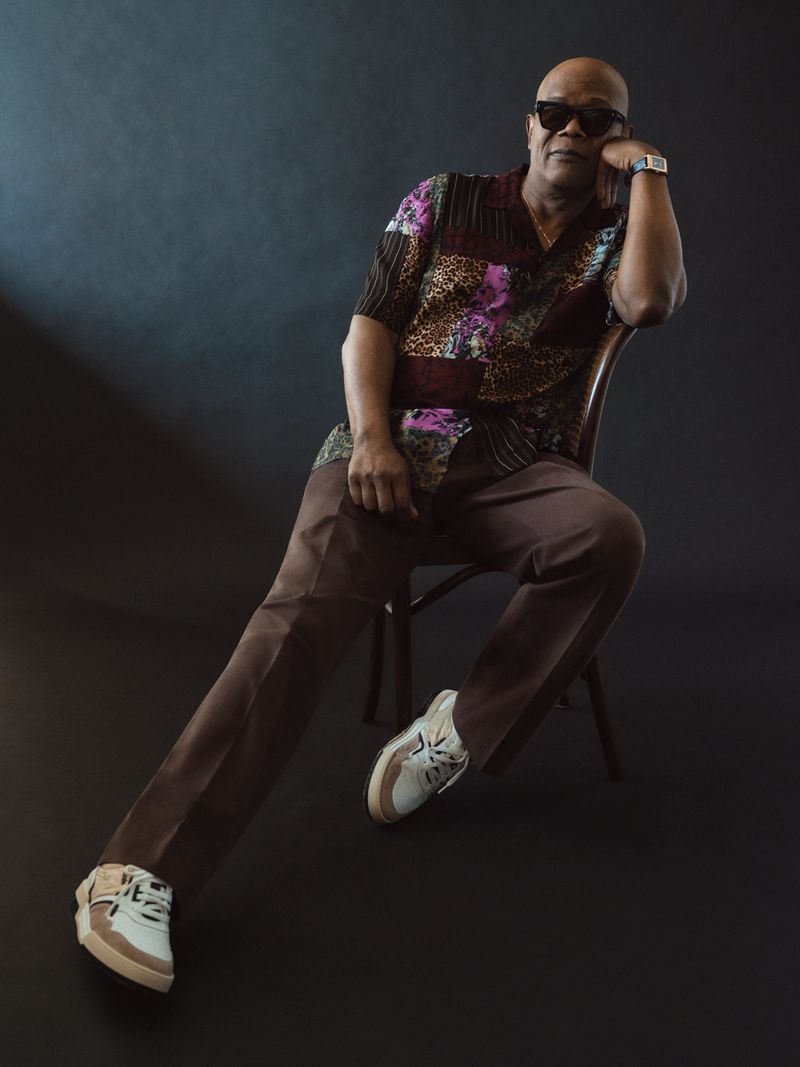

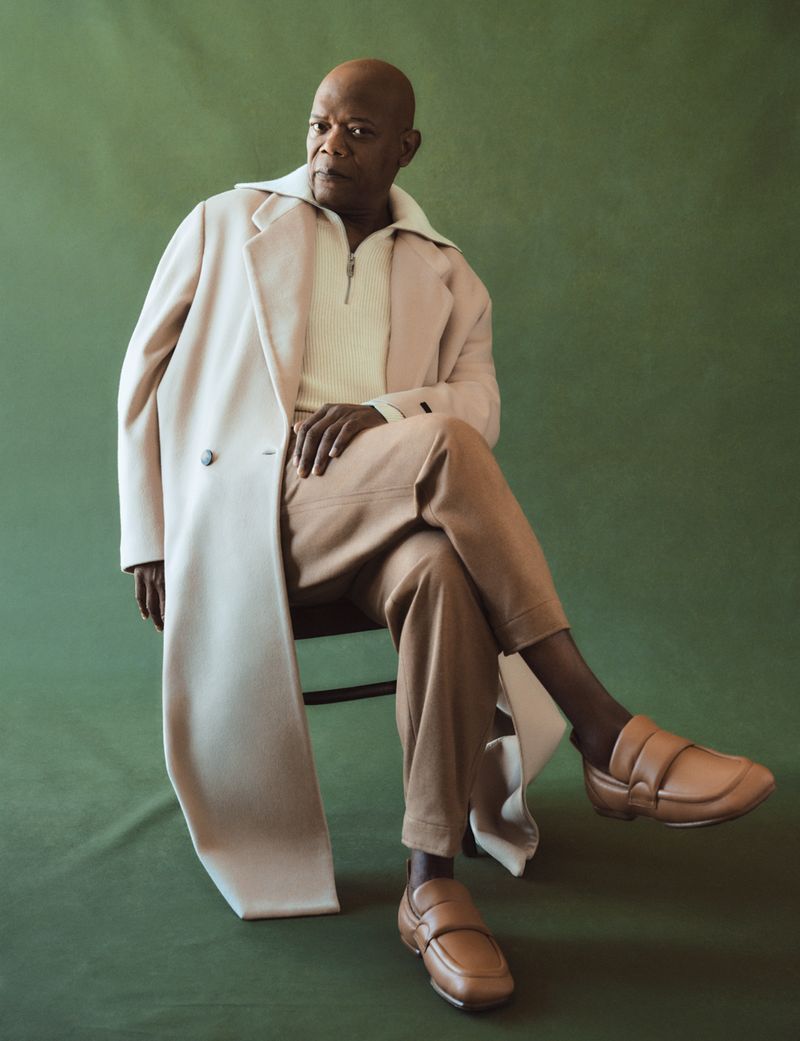

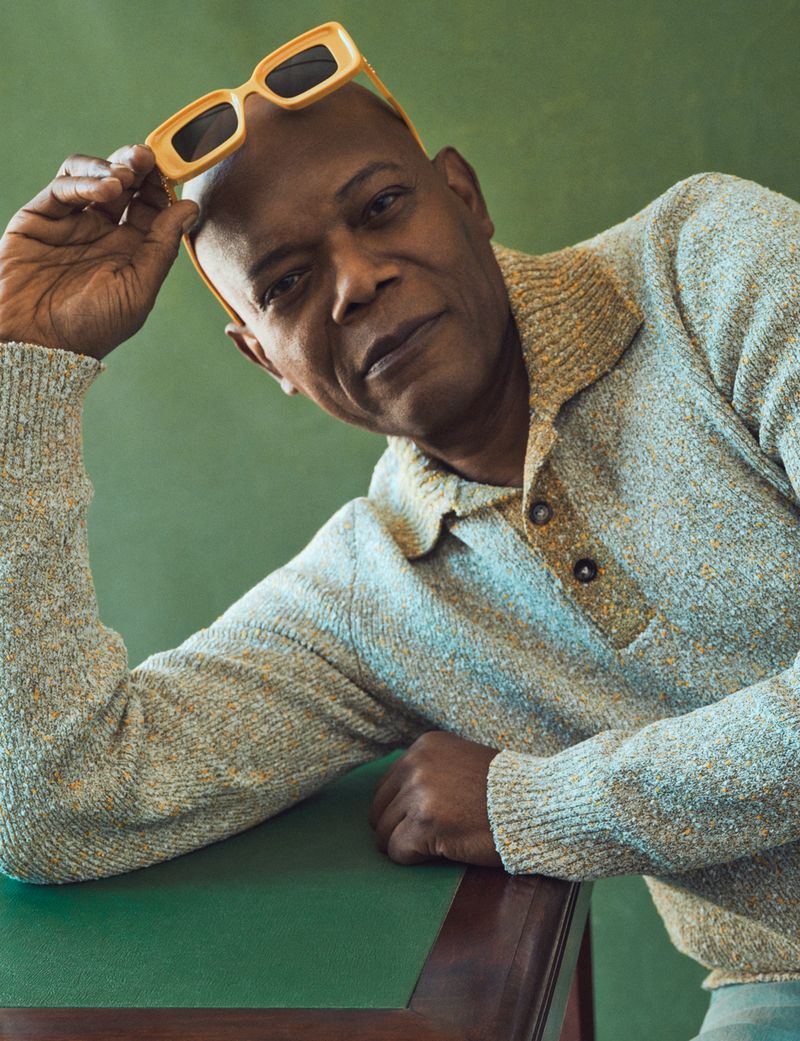

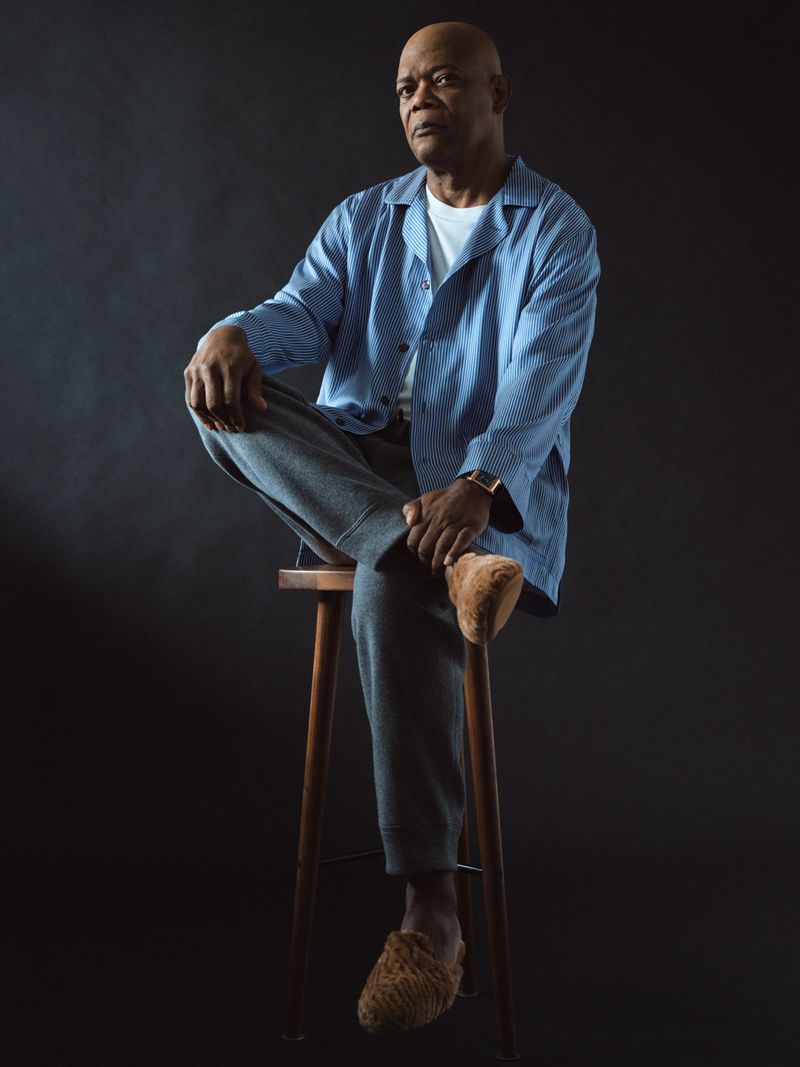

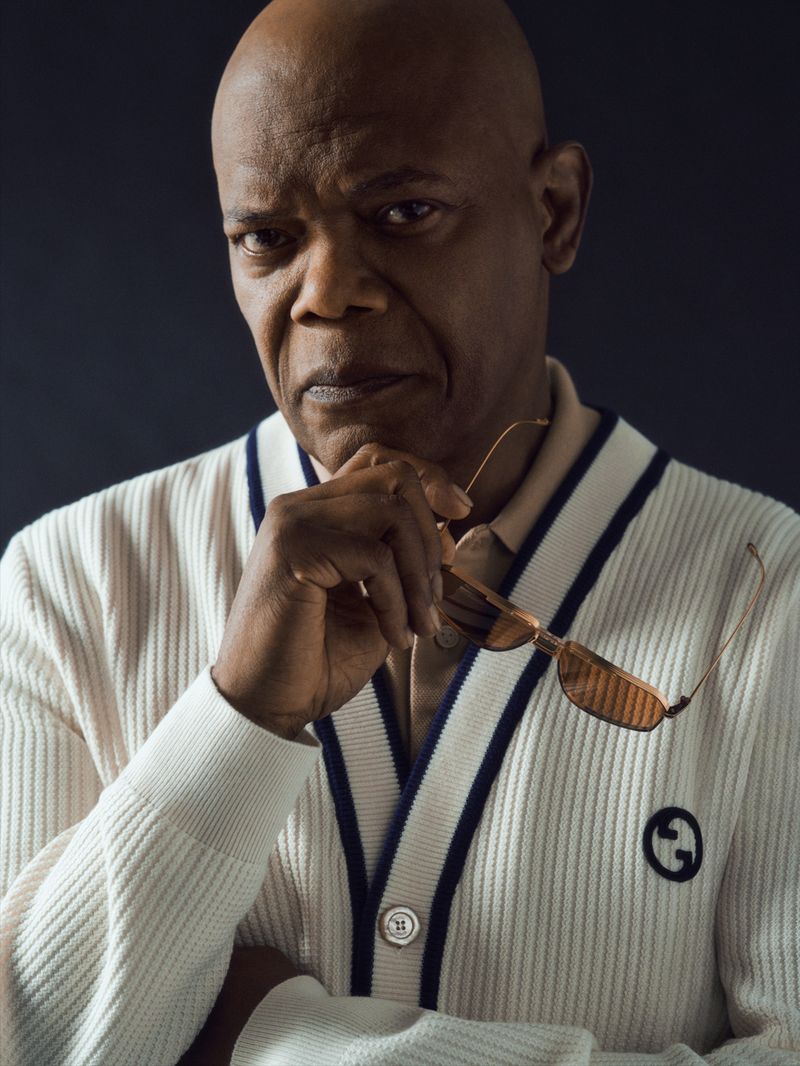

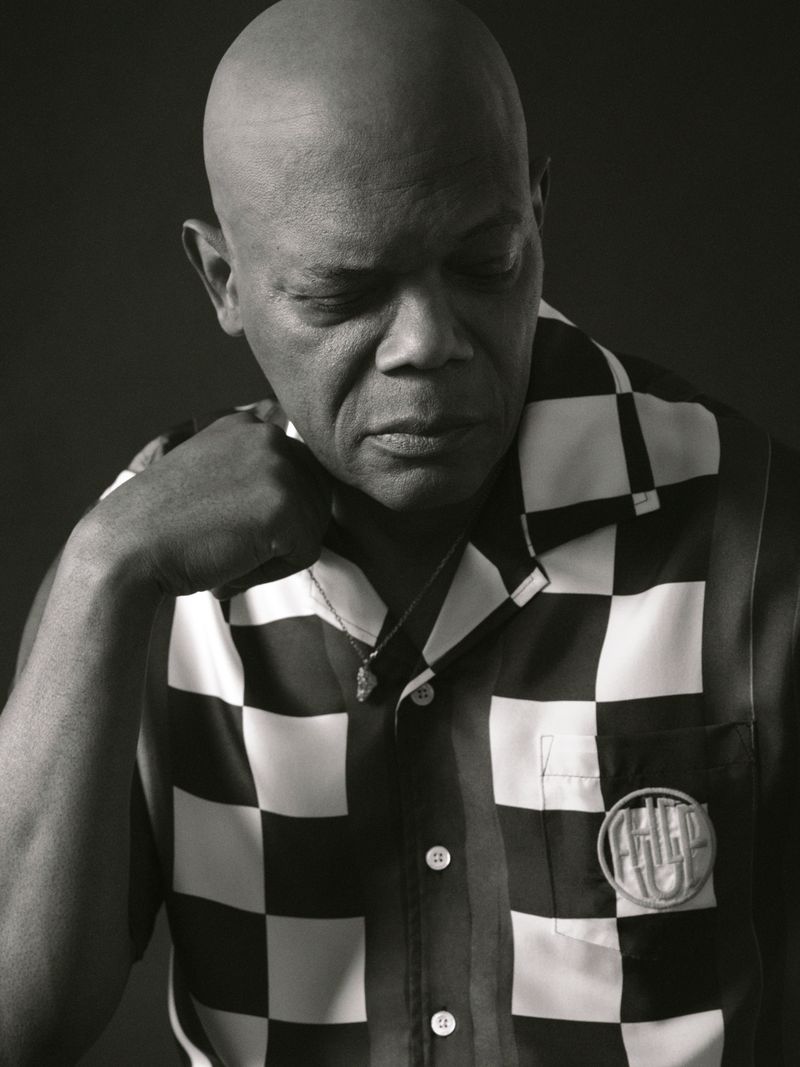

He poses in a number of looks for MR PORTER’s shoot this afternoon, but he arrives in a navy adidas sweat suit with white stripes, a red T-shirt and black sneakers with red stripes. The glasses of the day – he has hundreds of pairs; these are from a shop in London – are a light, goldish-brownish plastic. The frames are bookish circles that create two vortices where the grooves of his face seem to come together neatly. The bottom of the right lens is thick with fingerprints.

Moultrie takes a powder brush to the dome of Jackson’s head. They met while he was shooting a commercial for Apple in 2012. She is one of many longtime collaborators. He has had one publicist and they have worked together for 30 years. He has had one wife, Ms LaTanya Richardson Jackson, and they have been married since 1980.

He and Ms Judith Sheindlin – he loves to watch her reality court show, Judge Judy, in his trailer – have been close since Jackson moved to Los Angeles in the 1990s. They liked to get together and smoke cigarettes. When Judge Judy flew to New York, she would offer him a ride.

When she gave up smoking, she made him quit, too. Both did so with the help of a doctor who used sodium pentothal. “Truth serum,” says Jackson enthusiastically. The anaesthetic was a popular device in movies because of its supposed utility in extracting secrets. He adds that he still doesn’t understand why it works for smoking cessation.

“Did I ever think I was working too much? No”

He is a long-haul guy. His career has been punctuated by ellipses of exquisite symbiosis with directors, such as Mr Spike Lee and Mr Quentin Tarantino, and with massive franchises such as Star Wars and, most recently, Marvel. He has a nine-picture deal as Nick Fury. The latest instalment, a limited series called Secret Invasion, kicks off on Disney+ on 21 June. In the series, Fury takes centre stage as he and friends battle a Skrull invasion that threatens humanity.

With each of these partnerships, he has gathered new fans, like a march picking up new members around every corner until the whole town, young and old, is gathered on main street cheering for Mr Samuel L Jackson. He does not talk grandly about acting as a craft. He says he just wants to entertain and to “put butts in seats”. He has been very successful at the latter. He is the highest-grossing leading actor in Hollywood.

“Because I pick movies that I like, or movies that I would have gone to see when I was a kid – that’s one of the criteria I use sometimes when I’m choosing a movie – I ended up in all these great franchise films, which propelled me into more people’s psyches than, I guess, if I had done a whole bunch of indie films, little bitty films,” he says.

He takes roles in smaller projects, too, and has just returned from Scotland, where he was shooting the action thriller Damaged. He decided to do the film because he liked the story and was interested in his character, a Chicago detective who travels to Scotland to pursue a serial killer. He didn’t know who else was in the film before he arrived, but was delighted to find that he was starring opposite several actors he admired.

“The first woman I meet is the woman from Game Of Thrones, the woman who married Littlefinger and who had the son that was really weird,” he says, meaning the actor Ms Kate Dickie. Jackson is a devout Game Of Thrones fan. His voice rises several octaves in an impression of the son: “I wanna see the bad man fly!” He also saw Dickie in the film Red Road when he was a judge at Cannes.

“And then the bad guy shows up and he was my favourite character in Spartacus [Mr John Hannah].” Moultrie steps back and waits as Jackson bellows his favourite lines of Hannah’s from Spartacus, which are too carnal for publication.

“And then, a week later, Vincent Cassel shows up.” He sounds as starstruck as one would be running into, er, Samuel L Jackson.

“I don’t need to be in the most serious movie that’s being made,” he says. “I just want to be in the movie that I had the most fun making and that, I hope, people want to see. I’m not trying to change their lives. I’m just trying to make them happy. I’m trying to make them forget what’s going on in their life today and sit there and watch me.”

Jackson is not chatting so much as delivering. Sometimes he speaks quietly and conspiratorially, almost in a whisper. Several times, his sentences crescendo to a single booming word, spoken so loudly that it draws looks, then chuckles, from the crew milling around the hangar-like room that surrounds the makeshift grooming area. Someone who had no idea who Jackson was would immediately guess he was an actor and would probably also guess he was a great one.

After he recites the milestones of his career, Moultrie points out that he has also gathered young fans with Miss Peregrine’s Home For Peculiar Children and The Incredibles. The day before, while Moultrie and her 11-year-old daughter were having brunch at the Four Seasons, her daughter spotted Jackson before Moultrie did. “It’s neat that he has 11-year-old fans,” she says. “It’s like, here we go again.”

Jackson likes that a lot of older Black fans, in particular, still think of him as the guy from A Time To Kill, which was released in 1996 and which, he adds, should have won an Oscar. He also appreciates that for some fans, he will be for ever frozen in amber as Gator Purify, his character in Jungle Fever, the 1991 Mr Spike Lee film that he credits with getting him into Hollywood.

He has a reverence for the blockbuster. He recalls going to see Pulp Fiction with Mr Bruce Willis while the two were shooting Die Hard With A Vengeance. Willis told him that Pulp Fiction was good. “It’s gonna make you famous,” Jackson recalls Willis saying, “but Die Hard is gonna change your life.”

“I end up telling most directors, ‘I’ve seen this movie already and my character is not doing what you want him to do’”

Jackson has made at least three films a year since he began appearing in Lee’s movies in 1988. When I ask him whether he ever felt like he had taken on too much, whether, in popular parlance, he has ever experienced burnout, he looks at me, puzzled. Like, doing too many roles per year, I add.

A high-pitched laugh escapes him. “Did I ever think I was working too much?” he says. “No.”

He loves acting and, as with his doodles, he seems constitutionally unable to half-ass it, even though he could. The features that surround the job have changed since he started out onstage, he says. Now a car comes to pick him up. His per diem, he says, is “more than I made the whole time I was doing theatre”. He doesn’t do his own make-up any more. “It all changes, but performing and doing what you do and understanding the quality of what you want to be,” he says, you still have to work at that.

He prepares for films by thinking deeply about how to make audiences invest in his characters. When he is on set, he does not seek approval or, really, direction, from directors. “I generally end up telling most directors, ‘I’ve seen this movie already and my character is not doing what you want him to do,’” he says with a cackle.

He famously dislikes doing more than three takes for a scene. He is acutely aware of the extent to which an actor cedes control of his character once he has shot his scenes, so he guards his vision up front. From older directors he worked with, such as Mr John Frankenheimer and Mr William Friedkin, he absorbed a principle of “never shoot anything you don’t want in your movie” because, he says, the studio will come in behind you, recut it and change the story.

The limitations of film made it important for actors to approach their roles with profound intent. Jackson laments that newer directors don’t come up with the same sensibilities.

“You can’t see the film run out of the camera,” he says. “You’re not sending film off every day to be processed. You don’t know how much film costs. They don’t even say, ‘Cut!’ They just walk out and start talking to you at the end of the scene.”

Digital filmmaking has made it possible to do infinite takes for a single scene, each one different, so experimentation while shooting is now relatively harmless and inexpensive. But Jackson would rather not.

“I’m gonna do the same thing on every take,” he says. He has already considered at length how the way he has rehearsed his performance connects to the 75th scene.

“Sometimes they’re shocked,” he says. “Well, I’m just doing this because it has to do with something that’s going to happen way down the line that you haven’t given any thought to yet. But it’s gonna be a little thing. It’s not gonna be a big thing. It’s not gonna change anything. But it’s something for me.”

Jackson approaches our interview in a similar fashion. He is a jazzy talker, unapologetically using questions as platforms from which to soar away in a direction he prefers, even receding into fantastic monologues. (“That’s why I don’t do podcasts,” he says after a minutes-long imagined dialogue between Nick Fury and Nick Fury’s wife, which I feel confident would not receive the blessing of Disney+.) He reliably returns to roost on the original idea.

A woman pops her head in to tell us we have five more minutes. Five minutes later, Jackson has his phone out and a video he has pulled up is straining, through the spotty Wi-Fi, to buffer. He had mentioned that he had made a “beginner’s guide” to Game Of Thrones for HBO ahead of the release of the six-season box set. He was given a script, he says, but he went off-book. Now he holds the phone, in its blue plastic case, in front of us. When the video stops buffering, he hands over the phone and I hold it delicately.

He watches me watch the video, as invested as if he were explaining the show to me in real time. It is almost eight minutes long and I make a small anxious gesture at the people waiting for us to complete our interview, some of whom are now also watching me watch the video. “No, don’t worry about that,” Jackson says firmly.

The video is silly and schlocky, but it is a Jackson classic, which is to say he is more invested in it than he needs to be and it is more engaging than it should be. As with the rest of his oeuvre, even Snakes On A Plane and a few of the commercials he has done for Capital One, it demands the full attention of its audience.

Secret Invasion streams on Disney+ from 21 June