THE JOURNAL

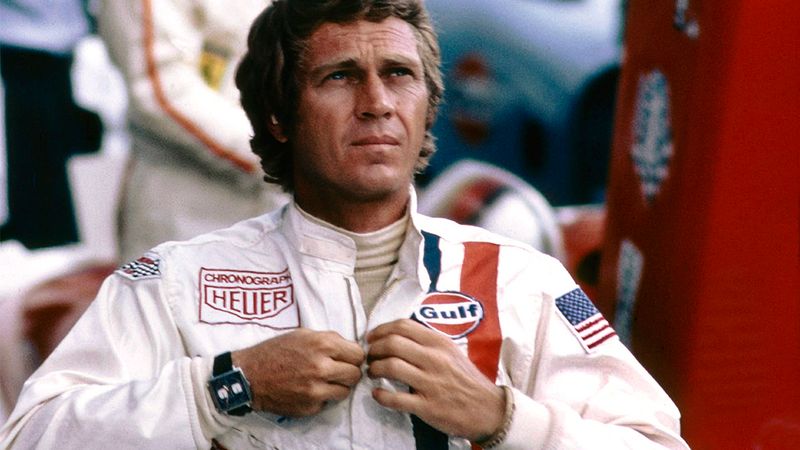

Mr Steve McQueen during the making of Le Mans, 1971. Photograph by Mel Traxel/ mptvimages.com

Are there any two words in the English language more likely to strike fear into the hearts of studio executives than “passion project”? The annals of cinematic history are strewn with them: sad tales of actors and directors drunk off their own success, indulging in projects that, if it wasn’t for their proven money-making record, would never have seen the green light, let alone the light of day.

Such was the case surrounding the notoriously troubled production of Le Mans, a 1971 racing movie that starred, and was produced by, the late, great Mr Steve McQueen. Based around the legendary 24-hour endurance motorsport race of the same name, Le Mans was the very definition of a passion project for Mr McQueen, who, as well as being one of his generation’s most bankable box-office stars, was also a keen racing driver who had just placed second in the 12 Hours of Sebring endurance race in Florida. He envisaged it as the ultimate motor-racing movie, and a tribute to a sport that had always been close to his heart. Instead, it became, perhaps, his greatest folly.

“I don’t think there’s any racing driver that can really tell you why he races. But I think he can probably show you.” These words, spoken by the man himself, are taken from a new documentary, Steve McQueen: The Man And Le Mans, that attempts to tell the true story of how the movie was made – and the unseen effects that its disaster-ridden production and lukewarm critical performance had on Mr McQueen. Weaving together outtakes with interviews of the surviving members of the production team and Mr McQueen’s family, The Man And Le Mans argues that this was more than just a movie to Mr McQueen: it was the first stage in his grand plan to build a Hollywood empire, and a career misstep from which he would never fully recover.

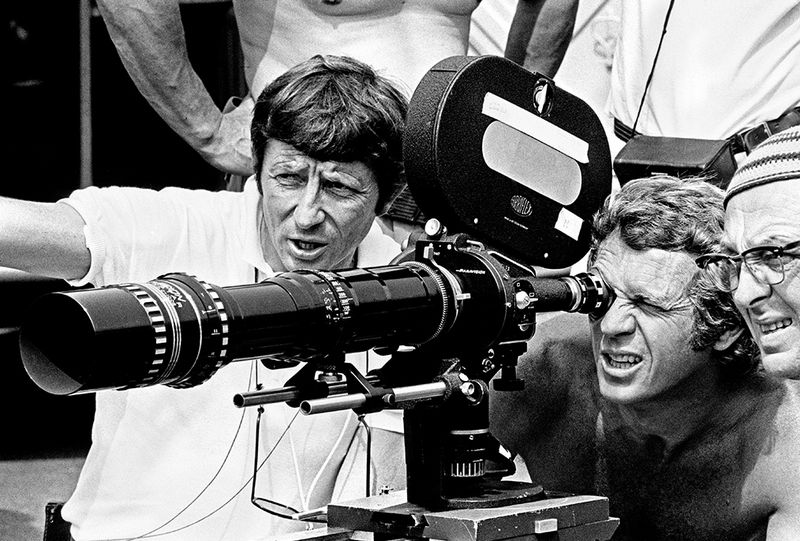

Mr McQueen behind the camera during the filming of Le Mans, 1970. Photograph by Raymond Depardon/ Magnum Photos

In 1970, Mr Steve McQueen had the world at his feet. The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape and Bullitt had made him a bona-fide star, the biggest in Hollywood. A global cinema and style icon, the “king of cool” could all but guarantee box-office returns, so when Cinema Center Films signed a six-picture deal with Mr McQueen’s company, Solar Productions, they must have thought they’d just been given a license to print money. They backed his first project, Le Mans, to the tune of $6m, at that time an astronomical figure (roughly $37.3m in today’s money), and brought in a raft of big-name Hollywood talents to help get it off the ground.

Sitting in the director’s chair was Mr John Sturges, the man who made Mr McQueen a star in Bullitt and The Magnificent Seven. Tasked with giving this petrol-head’s fantasy some semblance of a script was Mr Alan Trustman, who at the time was the highest-paid screenwriter in Hollywood. Before long, they would both be gone. Mr Trustman, who was unwilling to cede to Mr McQueen’s demands that the hero of the movie should lose the race, was fired. Mr Sturges, who found himself at loggerheads with his unruly leading man, walked off the set, expressing his frustration with the priceless words, “I am too old and too rich to put up with this shit.”

Mr McQueen and Le Mans' director Mr Lee H. Katzin, 1970. Photograph by Rob Walls/ REX Shutterstock

As one of the The Man And Le Mans directors Mr Gabriel Clarke explains, the movie’s financial backers soon found themselves in an uncomfortable position. “They had been sold the typical three-act Hollywood story, and Steve wasn’t going to give it to them,” he said. “And what’s worse, he never had any intention of giving it to them.” Before long, the men holding the purse strings decided that they had to wrest back control of the movie. They suspended production, put in place a new director, the relatively unknown Mr Lee H. Katzin, and forced new terms on Mr McQueen that saw him surrender his fee in order to get the movie finished.

Le Mans is now considered a cult classic film among motor-racing fans. Photograph The Kobal Collection

The final film is a testament to its own schizophrenic production process, as Mr Clarke’s co-director Mr John McKenna argues. “It is half the picture that Steve wanted to make, and half the picture he was forced to make. His vision was to give the audience a naked, raw portrayal of motor racing. Everything else was just compromise.” Unsurprisingly, and to Mr McQueen’s great credit as a film-maker, it is the breathlessly evocative, painstakingly captured racing scenes, and not the paper-thin suggestion of a Hollywood narrative, that has stood the test of time. Almost 45 years after the original movie debuted to a cool critical reception, it’s now considered a cult classic among racing fans.

The commercial failure of Le Mans may have scuppered his greatest ambitions, but it didn’t spell the end of his career. He would go on to achieve further success, eventually becoming the world’s best-paid actor in 1974 after box-office smashes The Towering Inferno and Papillon. But in the words of his ex-wife, Ms Neile Adams, who features heavily in the documentary, “the world became a different colour to him”.

Mr McQueen in between scenes on the set of Le Mans. Photograph Christophel Collection/Photoshot

Mr McQueen never lived to see his passion project reappraised. He was dead within a decade, the victim in 1980 of a rare form of lung cancer that some believe may have been caused by inhaling asbestos that was present in racing masks at the time. “He never showed up to the premiere [of Le Mans],” says Mr McKenna. “He made a decision to distance himself from the finished product. The way things turned out, I think it really hurt his pride. And yet, when he was showing films to the staff in the clinic where he died, it was Le Mans that he chose.”

Steve McQueen: The Man And Le Mans is released on 20 November 2015