THE JOURNAL

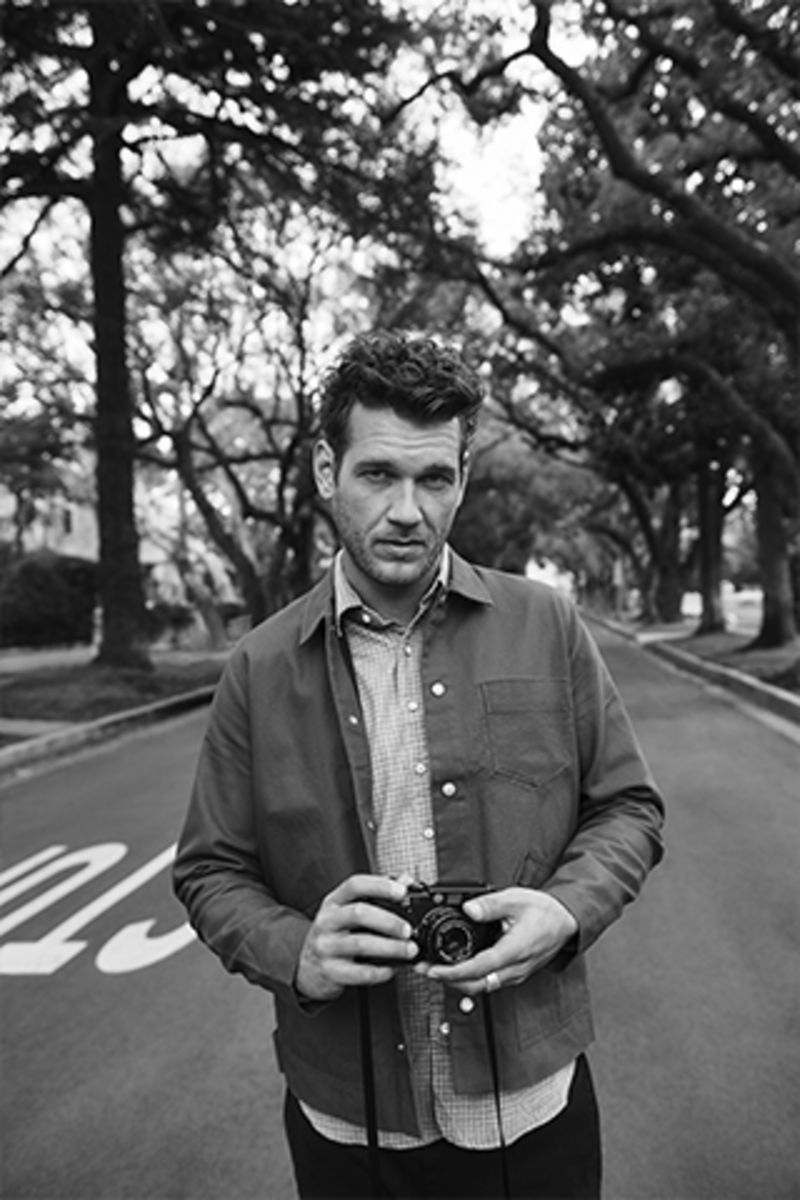

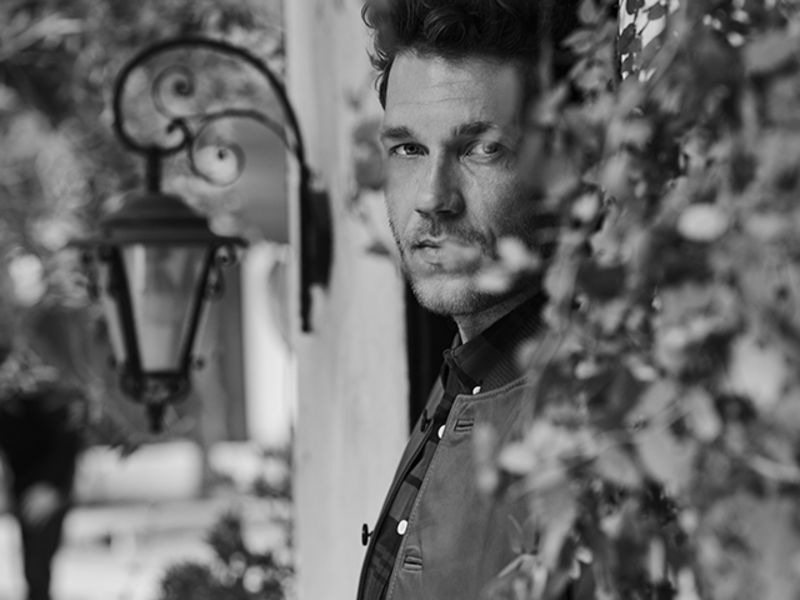

The skateboarding legend discusses teenage kicks, the highs and lows of the pro scene, and why he’s carving out a new career in photography.

As soon as he gets home – first things first – Mr Arto Saari fires up the sauna. “I’ve got some friends coming later,” he says, grinning. “You know – you can take the skateboarder out of Finland but…”

Mr Saari is one of skateboarding’s legends, right up there with Mr Tony Hawk. Skilful, elegant, brave, he has all the attributes you’d expect of a former Thrasher magazine skater of the year (2001), but it’s his story that marks him out from the rest, an extraordinary journey that his house, just off Hollywood’s Sunset Strip, tells in three simple chapters.

There’s the sauna, which he built himself – a nod to his home country, Finland, which he left at the age of 16. Next to it is a drained pool, symbolic of the southern California skate culture that lured him across the water and made him famous. And in the house itself, where he lives with his wife Mimi, four-year-old daughter Ella and two dogs, Banger and Bianca, the walls are covered in photos, most of them taken by Mr Saari himself. This is who he is now – a world-class skateboarder transitioning into photography, a leap that no one has made before him. But Mr Saari was always one for trying new jumps.

“I’m still a ‘pro’,” he says, making air quotes and grinning. That is, he’s still sponsored – by New Balance, Volcom and Flip – and he still goes on tour. In fact, he’s just returned from six months in Europe. But when it comes to skateboarding, he leaves the gnarly stuff to the kids. “I do some demos, but nothing death-defying,” he smiles. “That’s what six knee surgeries will do! Now, I prefer to shoot the tours.”

We sit in his office, surrounded by books by Messrs Helmut Newton, Ansel Adams and others. And with typical modesty he’s the first to admit he’s got a way to go as a photographer. He’s only been at it for two years, after all. But Mr Saari the photographer is a wonderful next chapter to what, at 33, has already been one of the most extraordinary stories in skateboarding.

It starts with a seven year old pushing around on a board in small-town Finland, raised by his mother, a humble secretary, and a bunch of uncles. Captivated by videos of skateboard pioneers including Messrs Hawk, Andrew Reynolds and Christian Hosoi, he devoured movies such as Thrashin’ and Gleaming the Cube. And he dreamt of California.

“It just seemed like a faraway fairyland,” he laughs. “Sunshine all the year round. Skate spots everywhere. Amazing.”

Thanks to the weather, there are only two or three months per year in Finland with favourable skating conditions. But in that time, Mr Saari got good enough to win local contests. And with all the bold innocence of youth he just pitched up at the world championships in Münster, Germany, in 1998, at age 16. It was a pro contest, but he didn’t care. “I had to fandangle [sic] my way in,” he says. And he killed it.

Flip, a then English board company, was instantly keen to sign him up. “They were like, ‘Hey, this random Finnish kid just won Best Street [the street skating portion of the competition]. He doesn’t speak English, but he can skate.’ And two weeks later, tickets for Vancouver arrived by FedEx. There was a skate show there. My mum wanted me to go back to high school, but I was like, ‘I got my passport. I got my ticket. I’m going.’”

Based in Huntington Beach in Orange County, Flip sponsored a lot of European skateboarders and well understood the challenges of relocating to a new country at such a young age. So it raised him in a way – housed him, clothed him, found him an accountant, kept him on the straight and narrow. In year one, he lived with fellow pros Messrs Geoff Rowley and Ed Templeton. By the age of 19, under the guidance of a realtor Flip had hired, he bought his first house. “I think it was the second place I walked into,” he says. “I was like, ‘OK, where do I sign? Because I need to go and skate right now.’”

The best part was touring. They did Japan, China, Europe, Australia. “There’s something that happens when you’re just searching for the next spot, the next pinnacle vibe – you’re completely free and moving forward.” Not to mention the rock band aspect. “Put a bunch of 20 year olds together, with a good amount of cash and no rules… But I never did hard drugs. It was mostly just booze and weed.”

Skateboarders are persistent people. “Concrete hurts,” says Mr Saari. “You’re not out there on the streets beating yourself up over and over again if you don’t love it.” But the flip-side is injury. And Mr Saari, at 6’2”, fell harder than most. Twice within the first six months of arriving in America, he found himself in ER with bad concussions. The first injury, featured in cartoon form in Flip’s video Sorry (2002), was brutal – sliding down a rail, he landed practically head first. Barely conscious, he was rushed to hospital. But of course he was skating again days later…

But it was his left knee that caused him the most grief. Again and again it kept blowing out. To get an idea of just how much time he was laid out, consider Mr Aarto’s three finest film parts, by his own estimation – Sorry, Menikmati and Mindfield. The first two he shot within two years – 10 minutes of footage in total. “The third is two and a half minutes and it took me seven years to make,” he says. “That’s a lot of injuries.”

To make things worse, Mr Saari’s response to injury was to drink. “Every time I did my knee, I had a complete meltdown,” he says. “Total depression. My career’s over. I’ll never be able to do what I love again. It was torture. And yes, I would drown my sorrows in a bottle.”

That’s a lot of bottles. So many that, by his late twenties, he had a drinking problem. A bad one. “My money was running out. My wife and kid had moved out. And I was pretty much drunk all the time. Nordic people haven’t been blessed with the most gracious drinking habits. Finns pass out on the street and start drinking when they wake up. I was this close to losing everything.”

That was 2012. Now, he’s two years sober, a regular at meetings and his family is back. “The wreckage is clearing,” he says. “There’s still a couple of fires to put out, but you know… “

Most importantly, he has found something to throw himself into that won’t jeopardise his knee. Photography is a way of keeping his love for skateboarding alive. “These kids now, they’re way better than I ever was,” he says, laughing. “But when I shoot them, I feel the energy and I can push the vibe and help them build their careers.”

Follow Mr Saari on Instagram here.