THE JOURNAL

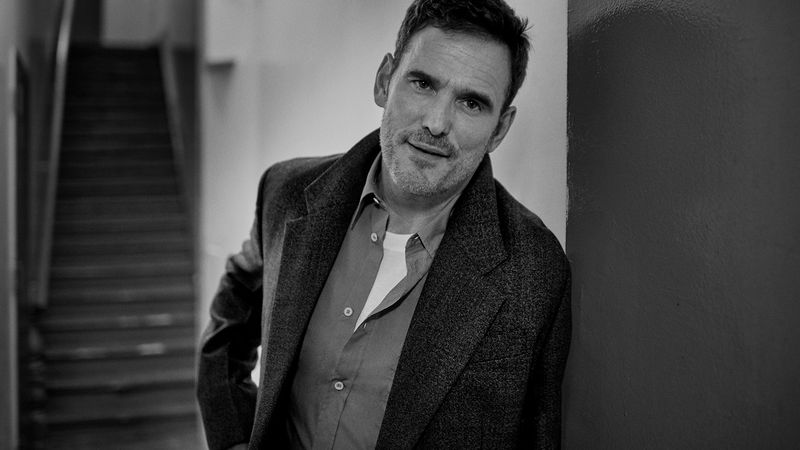

The star of 2018’s most controversial film fills us in on a few of his extracurricular activities.

“When you look at the way a child approaches something, they’re so uninhibited,” Mr Matt Dillon says. We’re talking about art and trust and limitations over hamburgers at the New York institution JG Melon, and we’ve gone right back to the beginning. “I went up to see my mother the other day,” he says, “and she pulled out all these old drawings my siblings and I did. They’re so ambitious in their scale: an enormous battle sequence, armies coming over the hill, castles, men being imprisoned in moats – all this sort of stuff that kids do... Vikings, warriors. You never, ever have the audacity to do that when you get older,” he says. “What’s great about kids is they don’t really focus on what they can’t do, they just focus on what they wanna do. It’s a beautiful thing.”

He smiles as he says this. A very big, bright, toothy smile – his famous smile, the one he memorably wrapped in camp and fake chompers in There’s Something About Mary; the one he can play for megawatt matinee idol glitz, or turn chillingly sinister, as he does in the forthcoming film from Mr Lars von Trier, The House That Jack Built, in which he plays a serial killer. Mr Dillon can at times seem to be many miles behind that smile, utterly disconnected from it, or deploying it to confuse, to appease, to distract. But talking about the creativity of a child – of himself as a child – the smile is pure. “A kid doesn’t say, ‘I’m not very good at drawing’,” he says. “They just do it. They draw a horse with a fucking cowboy on it riding over a hill. It’s kind of cool, right?”

But then the smile fades. Not in regard to the controversy around the film – the boos at Cannes, the shock-and-awe of Mr von Trier’s depictions of violence, mostly against women, children and animals. “I’m OK that people are upset,” he says. “It’s meant to be upsetting to you, and you should know, if you’re going to see this that it is going to some very dark, disturbing places. But I think it’s a good film. Really good. And I’m glad that I did it.” And there is an awful lot on his CV that he is immensely proud of. The work, after all, is the thing. “My friends tell me I’m better, happier when I’m working,” he says.

But then again, there’s the rest of it. The behind-the-scenes bits. The work it takes to get to the work. “There are a lot of aspects of my job,” he says, “rejection being one of them... There can be frustrations...” We savour our burgers in silence. The sound of the city is muted now, late in the afternoon. The heat and sun flood in through the open windows. He raises his arms wide, the cuffs of his red-check flannel shirt flapping. “But isn’t that life?”

These days, that life is pretty good. Since wrapping the film with Mr von Trier, he’s been on the road, filming a family drama with Mr Nick Nolte and Ms Emily Mortimer, shooting a space drama with Ms Eva Green, and spending time in Italy with his girlfriend of four years, Italian choreographer Ms Roberta Mastromichele. He has just finished directing a documentary about Cuban musician Mr Francisco Fellove. Not bad for a kid who grew up in New Rochelle, New York State, the second of six kids, raised by his mother, Ms Mary Ellen Dillon, and his father, Mr Paul Dillon, a forest-equipment sales manager turned fine-art painter.

And as we eat and chat, I think about the young Mr Dillon. It is sort of easy, and yet totally impossible, to imagine him as a middle-school kid in sleepy, suburban Larchmont, New York, in the late 1970s. Easy because, after his starmaking appearances in Mr Francis Ford Coppola’s two adaptations of Ms S E Hinton novels, Rumble Fish and The Outsiders, he became the sort of emblematic American teenager – much as Mr James Dean did before him. And impossible for the same reason: surely Mr Dillon, the real Mr Dillon, wasn’t in life the same aloof, anarchic, ambitious, violent, sensitive and charismatic kind of character he played in those films?

What we do know is that, while he was wandering the halls of his school one day, having ditched whatever class he was meant to be in, he was approached by two talent scouts (does this still happen?) who sent him to an audition. He was 14. And even then, as he would tell Mr Andy Warhol in an interview a few years later, “When I first went in to read... I said to myself, ‘I’m not going to let this pass me by.’” He didn’t. He booked that first film – Over The Edge, about a group of bored teens who rebel against their conservative town – and very quickly leapt to a very singular sort of movie stardom.

“I used to tell people I dropped out of high school,” he says, “but the good thing about it is you can study whatever you want.”

At first I’m expecting to hear defensiveness in this, an explaining away of something. But then a theme emerges: this is the child artist’s approach to education, an appetite-driven autodidacticism.

“If you were taking a literature major at university,” he says, “they’d say, ‘OK, you gotta read these eight books this summer, and then write about ’em,’ or something. I would not do well with that.” Instead, he says, he was able to follow his nose to all of his favourite writers, including Mr Jack Kerouac (he was nominated for a Grammy for his audiobook rendition of Mr Kerouac’s On The Road) and Mr Charles Bukowski, whose literary alter-ego, Henry Chinaski, Mr Dillon played in an adaptation of Factotum. The nose, too, is what led him to Southeast Asia in the 1990s, where he spent a lot of time in Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam, and from which he drew inspiration for the Mr Graham Greene-ish thriller City Of Ghosts, which Dillon wrote and directed in 2002.

But as much as raw instinct has been helpful, he allows that wisdom has had its place too. “I feel much more comfortable with the job than I did when I was younger, with what I’m doing, creating. Absolutely,” he says. “I think it’s because I’ve accepted it’s OK to get lost. Getting lost is part of what makes the medium work, right? Failing is important. The potential for failure is really important. You have to have the freedom to potentially not do it right, ’cause you can do it again, and you’re gonna learn from that. And that’s just part of the process. When you’re younger, you just go, ‘Oh, I’ve failed.’”

And when you are younger still, as he says, you don’t know from failure what you can’t do, only what you want to do. In that way, a child’s innocence is the greatest wisdom. They are able to create free from “the judge,” as he calls it, “sitting over your shoulder. Like that film Whiplash,” he says. “Now, it’s a ridiculous idea that this abusive band leader does this to this kid. But, if you look at that as a sort of allegory, that’s real. That’s real, what people do to themselves.”

Mr Dillon played a little percussion himself in his youth and knows all too well the abusive band leader in his head. After learning and loving to draw as a kid for example, he went to the Art Students League of New York at the age of 19. “And I go, ‘I’m gonna take a life-drawing class.’ And then I look at what everybody else is doing and I become totally intimidated: ‘I suck, I have no reason to be here.’ That’s where your mind goes. But what I’ve found now is there’s room for all of it: you can be critically minded with what you’re doing, and go, ‘OK, I’m not nearly as good as any of these people, but that’s why I’m here, to learn to get better, not compare myself with them.’ So that’s the difference.”

Mr Dillon’s father has become a well-respected painter in his second career; two of his great-uncles are giants of the comic world (one drew the comic strip Blondie, another created Flash Gordon); and he too has continued to paint and make collages – and loves just how different the process is from filmmaking. “It’s just you and the medium,” he says. “You don’t have to raise money to do it.”

But, when I ask him what makes him happiest, he says, “Collaborating with really good people.” This makes absolute sense for Mr Dillon, now 54, who hit another level working with Mr Gus Van Sant and Ms Kelly Lynch in Drugstore Cowboy, for example – like a charming, terrifying, devastating and brilliant Mr Montgomery Clift-style conman on dope. And who knew he could be so deadpan hilarious as he is, in full grunge-era glory, as the musician in Singles (“We’re huge in Europe right now”) – well, Mr Cameron Crowe did. Collaborating with Mr von Trier seems to have been similarly profound for him – thrilling, dangerous, fun, and... well, I’ll leave you to judge the results.

So, frankly, despite his stated frustrations, he seems to have the creative work thing dialled. Which gets me to wondering if his work wisdom can be applied elsewhere – to life, for example. I mean, surely the innocence and audacity of a child artist can’t help me in my day-to-day? In life it is a little more precarious to get lost than it is in a performance, or a picture. And in life, as opposed to the making of a film, without the option to do multiple takes, it is devastating to fail.

“Yeah,” he says, “but tomorrow’s another day, right? You do get to go again. You learn from your mistakes. And in a smaller way you can say, ‘Let’s try this. Oh, that didn’t work, so let’s go back to the other way we were doing it,’ or, ‘Let’s try something else.’”

He likes the sound of that, and chases it with a big smile.

The House That Jack Built is out 14 December