THE JOURNAL

Mr Walid al Damirji, the brains behind the upcycling brand, creates artisanal takes on bombers and sweatpants from the vintage textiles he collects.

Mr Walid al Damirji does not have PR people. I’m sorry, what? Everyone has PR people in the fashion industry. Most up-and-coming London designers get one before they’ve even had the chance to blow the last of their student loans. Sometimes, such is the number of emails that fly back and forth in liaising with brands, it feels as if the PRs have PRs. But no, to arrange an interview with Mr al Damirji, you have write to him personally, which feels a little weird, but good weird.

“I have no interest in a circus scenario,” says Mr al Damirji at his studio in London’s Mayfair, somewhat unexpectedly hidden away in a mews full of car-repair workshops. “People get trapped in that whole thing of fashion, fashion, fashion… and then you’ve got to have a show, get a PR company to do a party. And where are the priorities? Our target is to create beautiful garments and send them out, and have them visible in the shops. What more would we want?”

It’s a common sense, albeit lo-fi approach – but one that’s far from run-of-the-mill. In truth, there’s very little that’s regular about Mr al Damirji and his brand, By Walid, which has been quietly building momentum among style aficionados – without the aid of press releases, cocktails and canapés – since its launch in 2011. It's a collection of clothing made from repurposed heritage and antique fabrics, some of which date as far back as the 18th century. And if this recycling-upcycling concept is unusual, the way it’s applied is even more so.

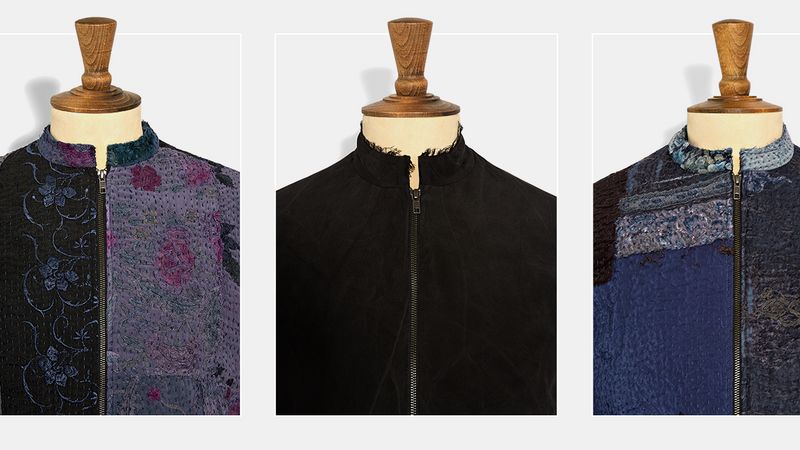

Every fabric used in By Walid’s collection is a mixture of many different repurposed textiles – from 19th-century French damask to embroidered silk kimonos to Victorian table linen – cut and sewn together by hand on an organic cotton base with an embroidery technique reminiscent of the traditional Japanese art of boro. Each fabric is then hand-dyed before being turned into the final garments. These are then hand-finished, resulting in pieces that, in every detail, are one-of-a-kind clothes.

The overall vibe is deconstructed sportswear, executed with a slouchy, romantic silhouette and embellished with raw-looking, unfinished hems. Typical pieces include luxuriantly soft silk bomber jackets, made from repurposed kimonos, patchwork sweaters in cotton jersey and loose drop-crotch sweatpants made from overdyed embroidered linen fragments. If the results are impressive, the process of getting there sounds pretty exhausting. “We’re very artisanal,” says Mr al Damirji, somewhat understating the point. “It’s very much a small cottage industry.”

Given this heroic attention to detail, it will come as no surprise that Swiss-born Mr al Damirji is something of an industry veteran – a self-described “clothes horse” who, as well as being a former creative director of high-end British fashion label Joseph, has worked as designer, producer, buyer and merchandiser for apparel in a career spanning three decades. (He is also the co-founder of boutique chocolatier and bakery Cocomaya, which he started in 2008 after selling his previous business, a high-end clothes production company, though he’s no longer involved. “I put on so much weight,” he says. “Never again!”)

By Walid started, as it has continued, as something of a word-of-mouth affair. The first piece was a coat in 19th-century linen, which Mr al Damirji made for a friend, who subsequently convinced him take it to Paris. “I was like, ‘Oh, f**k off, I don’t want to do that. Leave me alone’,” says Mr al Damirji. “But anyway, I took I think four jackets with me to Paris, borrowed a friend’s apartment [to show the clothes], and we got orders for 800 jackets, just from one style. [Buyers] said, look, we can’t just have jackets, you’ve got to give us a full collection… and that’s how I got sucked back into it.”

Today, the studio is not only festooned with piles of fabric – some yet to be dyed, some in the process of being cut and collaged – but full to bursting with a rail of stock waiting to be sent out. Upstairs, a roomful of students from Central Saint Martins and Winchester are furiously prepping fabrics, drafting patterns and making minute adjustments to the fit and feel of samples. Evidently, business is good. Given the hand-worked nature of the pieces, how does Mr al Damirji manage to keep up with it all?

“We say no to an awful lot of people,” he says. “The store’s got to be right to be carrying the product. It has to understand it.” The understanding part, apparently, is not always straightforward. “We do a lot of training, where we explain the fabrics to the staff,” says Mr al Damirji. “I think one shop the other day said I was a Lebanese socialite. That freaked me out a little bit! A Lebanese socialite… Oh, and the fabrics come from Syria! I was like, ‘What?’ So I called them and I said, ‘Training tomorrow!’”

Mr al Damirji may not have gone quite so far afield as Syria for the sake of fabrics, but his quest for the world’s hidden textile treasures means he is constantly on the lookout for new acquisitions. “I spend most of the day on the phone,” he says, “or receiving dealers, or speaking to auction houses. It’s a major investment. We have to stockpile them continuously. All year round, basically.”

Such vigilance reaps strange and wonderful rewards: hanging on a rail at the side of a studio, for example, is a jacket that has been made entirely from children’s gloves from the 19th century. There’s a coat with flap pockets made from a pair of crocodile handbags. “There’s always something out there that you can do, that you can expand on,” says Mr al Damirji. Of course, such materials don’t come in infinite quantities. Even so, he assures: “There is enough.”

Mr al Damirji’s stockpiling, as well as his intelligent repurposing of odds and ends of fabrics means that By Walid is a “zero waste” operation, but it also allows him to create continuity between collections by bringing back fabrics from previous seasons into newer creations. It’s important to Mr al Damirji that these repurposed garments, having been made from unwanted fabrics themselves, “are not seasonally disposable”. One of the ways he ensures this is by sticking to favourite silhouettes in the men’s collection, innovating with fabric choice and construction rather than continually introducing new shapes. But of course, the clothes are also intended to be keepers – investment pieces that, in the details of their fabrication, can be cherished for their uniqueness. “What’s more luxurious,” says Mr al Damirji, “than having a one-of-a-kind garment?”