THE JOURNAL

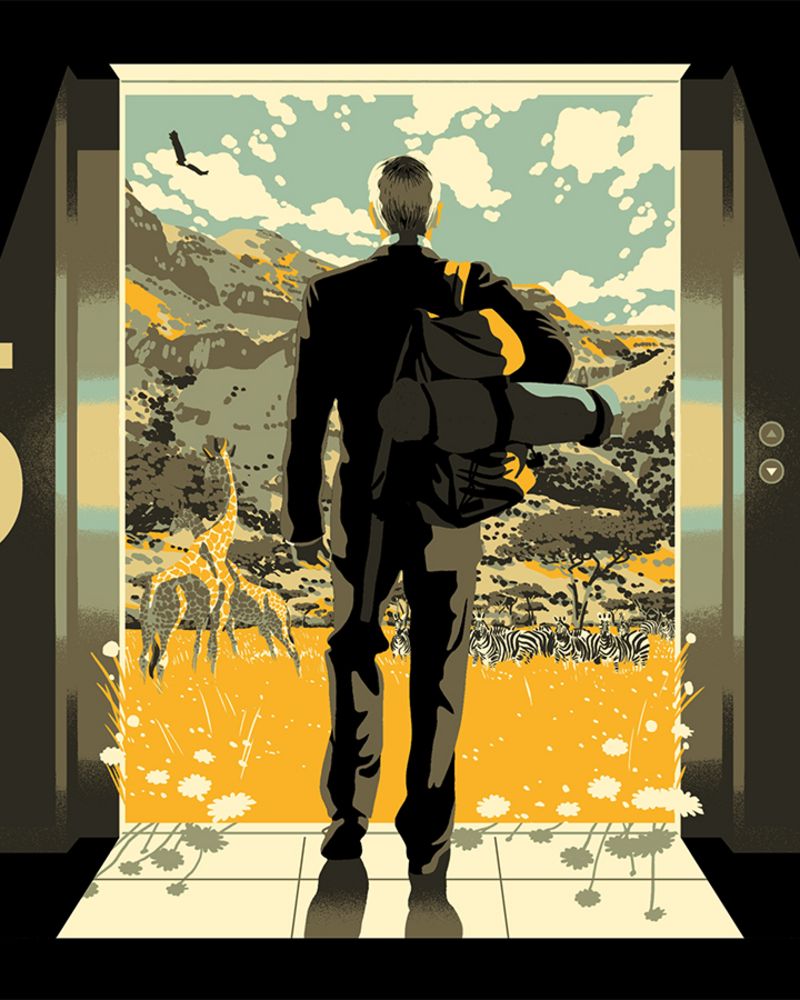

Illustration by Mr Timba Smits

Back in 2010, when I was at university, a video went viral on YouTube called Gap Yah. It depicted a caricature of an insufferably posh man talking on the phone about his travel experiences in various exotic locations. The punchline (so you don’t have to watch it): whenever he is on the cusp of having a meaningful cultural experience, he ruins it by getting drunk and “chundering everywhere”. In 2023, I imagine young people use time out before or after university to work for a charity. When I was 18, gap years were for living in 20-bed hostel dormitories in countries that facilitated the daily cheap consumption of alcohol in deep-sided bowls.

Unsurprisingly, there is nothing appealing about the concept of a gap year to me as a 34-year-old man. Every time I mentioned to friends and family late last year that I was taking eight months off to travel along the coast of West Africa and someone said, “Oh, like a gap year, then?” I bristled. “No, this is not a gap year. It’s like… a long holiday. Well, not a holiday, because I’m going to be working as I go. No. No. I am not a digital nomad, for God’s sake. No. I’m just going away for a bit, OK?”

When you are 23, long-term travel fits the idea mythologised in literature and film. You are the novelist Mr Jack Kerouac. You are one of the handsome boys in the film Y Tu Mamá También partying and sleeping with older women. These clichés don’t wash when you are older, and nor should they. My Instagram pictures are supposed to portray culturally enlightening adventures. They may show the workings of a circuitous avoidance strategy for life’s admin decades.

According to Mr Lee Thompson, founder of Flash Pack, a travel company that organises six-month (or longer) trips for people in their thirties and forties, everyone is at it. “Popularity in adult gap years is soaring right now,” he says. “As people get higher up the career ladder, they negotiate a sabbatical, six months out, etc. If you prove you’re indispensable at work, nine times out of 10, you’re going to get a yes. Companies understand the importance of taking a break now. Remote working, post-pandemic, being able to work anywhere has really helped.”

“People think, is this going to set me back in terms of career? If you can keep connected to your industry and introduce what you’re learning, it’s potentially a huge advantage”

I am able to go away for an exorbitant amount of time because I have relatively few responsibilities. I don’t have a mortgage, children or a partner and I work as a freelance writer wherever there is a desk and Wi-Fi (not a given in West African countries), so I did not have to save a chunk of money. If I don’t do this now, I thought, I never will if I ever get round to the three things everyone else my age seems to be doing – having children, starting a podcast or building an extra wall in your house, for some reason. All I needed to do was sub-let my flat in a contractually problematic manner, put my belongings in my friend’s attic, pack a bag and buy a ticket. As a traveller in West Africa, you can spend less than £1,000 a month without budgeting. If you have different aspirations, and more complicated circumstances, a grown-up gap year is surely less viable.

Not for Mr Ben Keene, who is in his forties and founded Rebel Book Club. He took a year out in 2018 with three children, a wife, a house and a career to consider. After Brexit scuppered his plans to sell his property, he rented it out instead and decided to broaden his horizons. But not without some careful deliberation.

“We had three criteria,” he says. “The climate, culture and experience must be very different from what we know; I would have access to decent Wi-Fi to do remote work; and there was an international community to tap into, a kids’ primary school.” Sri Lanka and Bali were both on the table, but, after cruising around the world on Google Maps, he stuck a pin in Koh Lanta in southern Thailand. “We got all our medical stuff sorted and I got things in place workwise and we did some saving. Do as much financial planning and forecasting as you can.”

After staying in an Airbnb for a week, they found a rental property for £1,000 a month. The family spent their days swimming and eating fresh fruit and cheap street food. They appreciated the island clichés. Life is punctuated by the tides and sunsets, rather than train timetables and Strictly Come Dancing. But what of the cliché about trouble in paradise? “The hard bit is feeding the kids,” says Keene. “And you can’t really go outside between 10.00am and 4.00pm, when it’s pushing 40 degrees.” Idylls are built on forms, too. “The administration around travel takes a lot of time. You’re doing everything multiple times [for your family]. It’s an extra job.” He also missed his traditional support networks.

The experience sounds like a once-in-a-lifetime thing, then. Would he do it again? “One hundred and ten per cent yes,” he says. “It’s part of the kids’ story. We made some great friends. Being away from the UK gave us perspective. We stopped worrying about things we used to. People think, is this going to set me back in terms of career? If you can keep connected to your industry and introduce what you’re learning, it’s potentially a huge advantage.”

Another option is to cut all ties, drop everything and hit the road True Romance-style. Ms Patricia Pamplona and Mr Wesley Klimpel are a married couple in their thirties from São Paulo who work as journalists. Or they did. Suffering from burnout, and with a shared desire to experience other cultures, they left their jobs at a newspaper, gave up their rented apartment, sold everything they owned, gave power of attorney to relatives and, on 31 October 2022, embarked on a three-year round-the-world trip. “We don’t want to return to Brazil,” says Klimpel. “We are motivated to get to know the world,” says Pamplona.

It all sounds very romantic and hedonistic, but why did they not do it in their twenties? “We wanted to build a career first,” says Pamplona pragmatically. “We are passionate about journalism and its importance to the world.” There are more practical benefits to being a bit older, too. “We can avoid dangers,” says Klimpel. “We have more knowledge and we know more people. And, now, we have more money.”

The couple get around using whatever public transport there is in the country they happen to wake up in. They use travellers’ Facebook groups and apps such as iOverlander, where niche accommodation and route information are shared by global nomads, and international banking apps such as Wise. Their biggest obstacle? You can’t learn “Where is the Brazilian embassy?” in 7,000 languages. “You mime,” says Pamplona. “There is a lot of pointing.”

It seems, in a hyper-connected, remote-work world, where we are all quietly quitting or giving up on traditional concepts of success, there have never been fewer obstacles for long-term travel. In the past week, I have heard about 74-year-olds spending half their year in Thailand, 41-year-old single professionals on sabbaticals in Asia and Africa, and 50-year-olds who took their family to France pre-pandemic and ended up staying for a year. The caveat is that we change how we travel. Instead of partying and sleeping around like we did in our teens, we might be looking to build character. Instead of travelling before a work commitment, we might have to take it with us. Instead of hostels, it might be Airbnbs. Or, in later life, we don’t travel on our own. We go as a family unit.

Not necessarily. Mr Peter Ziegelwanger is a 50-year-old pilot from Austria. He has two children and is newly divorced. He takes long-term solo trips every year and has no plans to stop. “The way I travel now is exactly the same as I did 30 years ago,” he says “When I was young, I had no money. Now, I could go on much more luxurious trips, but I want to sleep in the cheapest hostel and eat street food and travel in the cramped buses. You can’t watch the world from your fancy hotel.” Recent trips have taken him to Swaziland, Mozambique and Malawi. “It’s this thing, I want to know what’s around the corner,” he says. “I hitchhike. I carry an 8kg backpack, which includes my tent and sleeping bag. All I think is should I take two T-shirts or three? You don’t need anything else. The lighter you travel, the more you live in the moment.”

WhatsApp and improved phone sim connectivity mean Ziegelwanger can contact his children from pretty much anywhere on the planet, although he is aware that it makes him more disconnected from the place and people he has come to interact with. He continues to travel to test his mindset. “When you’re older, your mind is more blocked,” he says. “Travelling is one way to open my mind and get new perspectives, especially on your own life. There is no age limit [to travel]. There is only a mind limit.”

Forget full-moon parties and 10-hour bus journeys. Ziegelwanger suggests you can grow out of the desire to learn from other cultures. This may be true, but in “Why Do It?” from his essay collection Here & There, the journalist Mr AA Gill suggests we should not expect travel to make us better people. “Travel doesn’t broaden the mind,” he writes, “but it does give you interesting blisters.” If we stop fretting about why we are boarding the plane, or what we will get from the destination, there is no reason not to keep moving. You are never too old to need petroleum jelly.