THE JOURNAL

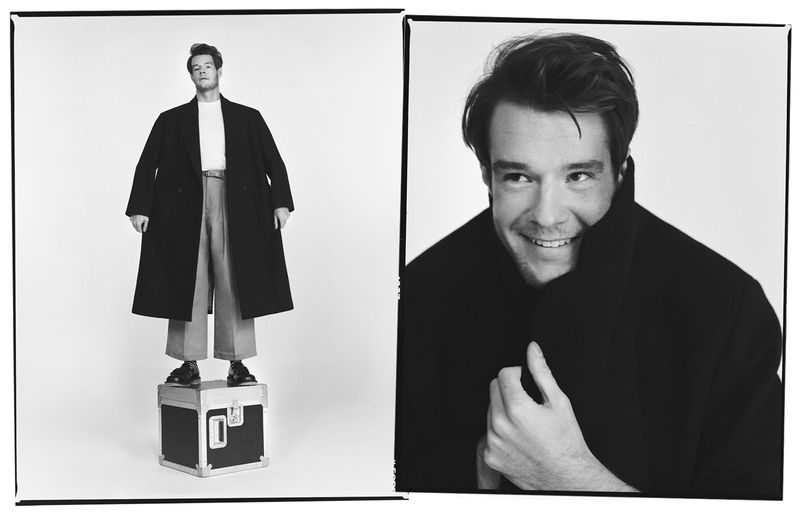

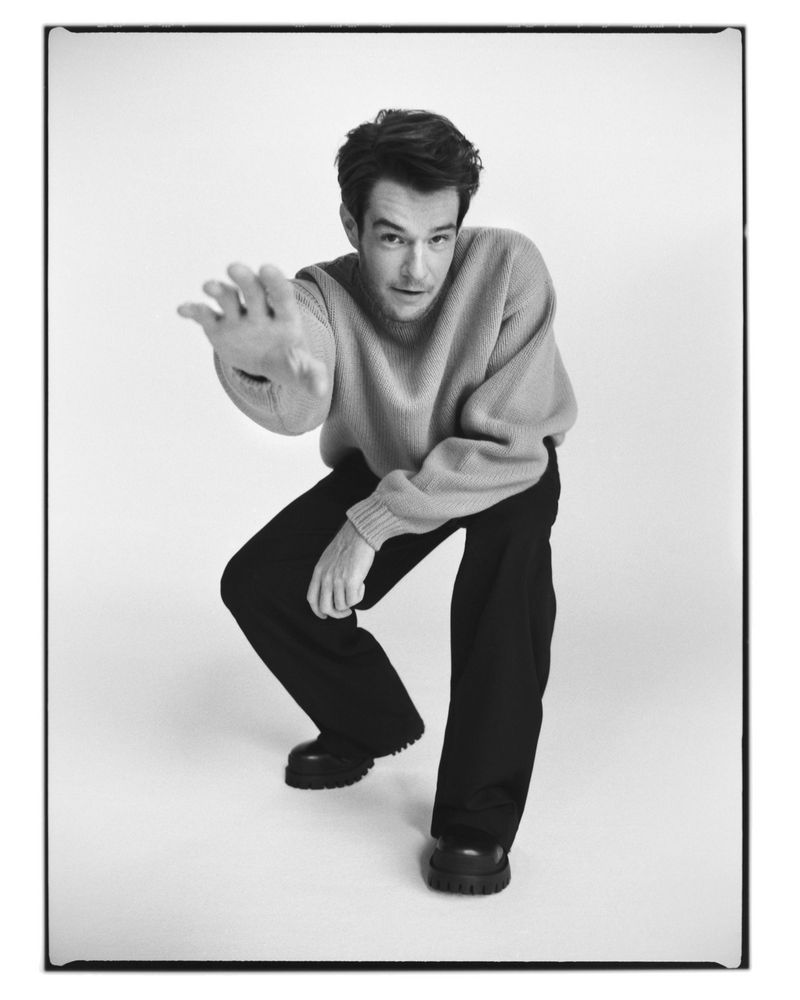

Actors, it is said, need motivation to be truly great. For Mr Connor Swindells, his motivation was his days spent digging holes in the dirt while building fences. A job he “hated”, but one that he knew the grammar of, intimately. You see, Connor Swindells is not the rule: a working-class lad from a line of farmers and labourers, in an industry dominated by middle-class men without a calloused hand in their history. Moreover, he’s a 24-year-old who holds himself with the class and control of a seasoned 40-something. A quiet, private star, who prizes creative collaborations over any trappings of fame. Connor Swindells is the exception.

You’d imagine, given that he’s now starring in one of the biggest shows on television, globally, that a trapping or two may come his way. In fact, Sussex-born Swindells is only just getting his head around the notion of success and life post-labouring: “The ball’s been rolling quicker than my feet will go for the last couple of years,” says a reserved but smiling Swindells over Zoom, meowing cats by his side. “Now is the time where I’m just catching up and realising the magnitude of everything.”

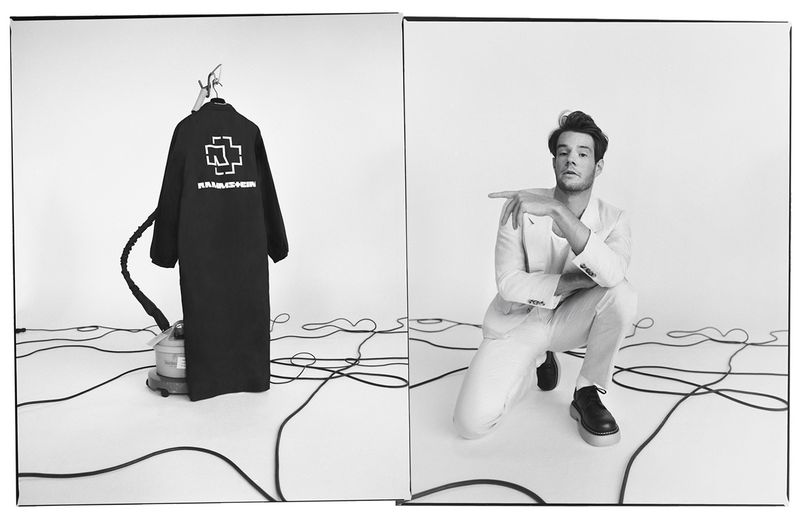

Magnitude is the right word, given that the aforementioned behemoth TV show, Netflix comedy-drama Sex Education, is about to return for a third season. What does he put the rapturous reception down to? “It’s a new thing for people around the world, where to us Brits, it’s a familiar comfort. We love that kind of vulgarity within sexual humour.” It’s clear that for Swindells, the creative opportunities for an actor of his sensibilities is a huge pull. “It gives you freedom. You can really get away with murder because it is stylised and it is over the top at times. There’s no scenario or circumstance where the audience isn’t going to buy it.”

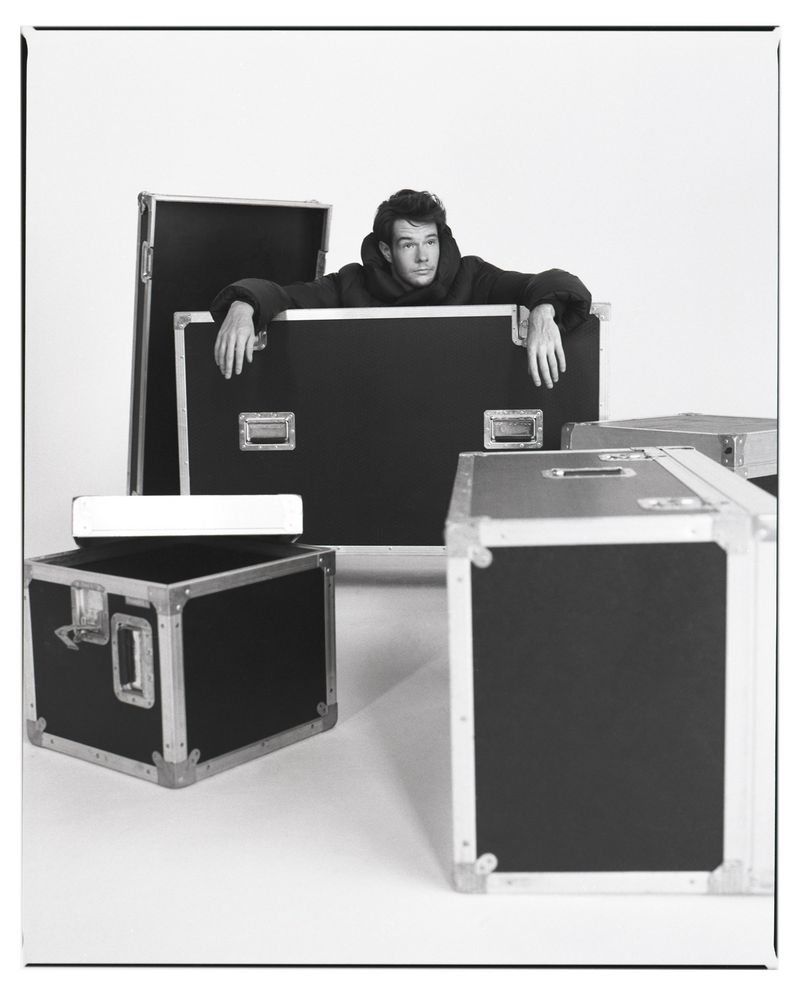

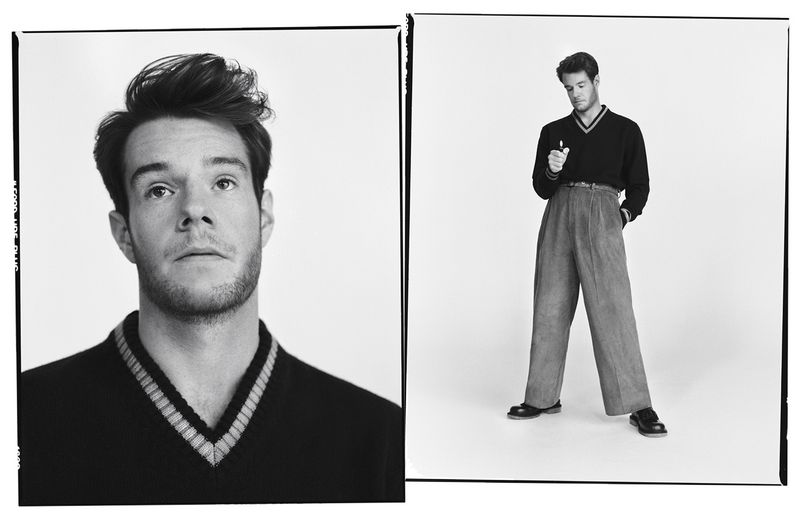

Swindells plays Adam, a teenage bundle of toxic heteronormative masculinity messed up by his cold relationship with his dad, and saved (potentially) by his tender relationship with fellow student, Eric (Mr Ncuti Gatwa). “Adam is a young man wrestling with his masculinity, who is quite ridiculous in nature,” Swindells says. “At the start, he put up a lot of walls around him and a lot of survival mechanisms. And as the show goes on, we start to peel away those layers and see what a scared little boy is sitting inside of him, which I think will resonate with a lot of men.”

The end of season two saw a possible breakthrough for the couple – and for Adam’s acceptance of his sexuality – but as season three opens, it’s also plain that Adam’s bully of old still has a heap of knotty stuff to work through. “I think like a lot of young boys, anger is far more accepted than fear, even though they’re both coming from the same place,” says Swindells. “For so many young boys, myself included… I’d never get upset, but I would get angry and destructive.”

Swindells’ own school life clearly wasn’t a bed of roses or even particularly memorable. “I was quite withdrawn,” he says. “I never made an impression. I never did much, much to my regret later on in life. I wish that I had tried harder or at least pissed off a few more teachers, so I could go back and wave it in their faces.”

If he did go back, there would be one teacher exempt from the face-waving. His Year Seven drama teacher, who saw something in him that no one else had; that he hadn’t even seen in himself. She declared that one day he’d act professionally, something Swindells thought “wasn’t a serious job to do at all.” Undeterred, she talked him into the school production of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. “She wrote me a new character,” he remembers. “It was the lion, the scarecrow, the tin man and… the army private.”

Teenage Swindells’ first night on stage, in front of an audience, is something he remembers with clarity. “For the first time, I was OK being the centre of attention. To have all eyes on me and to hear people laughing was a nice feeling for my ego, as a quiet young boy.”

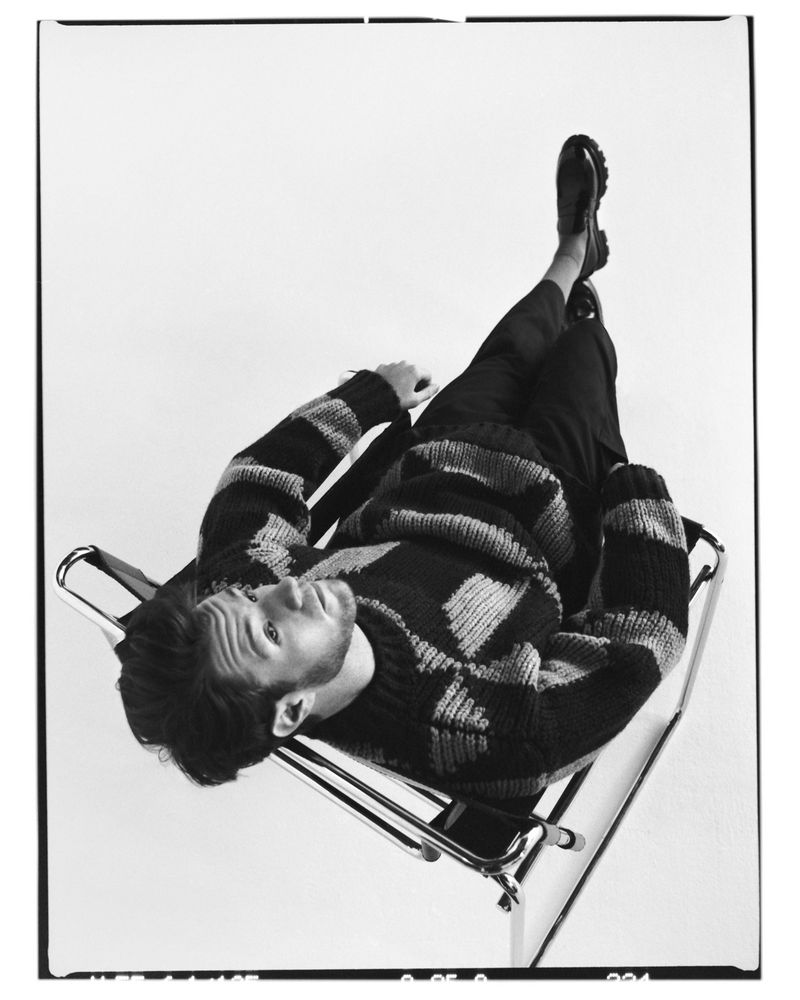

It was only a sojourn into acting, though, because Swindells had something else in his life, a sport that kept him out of trouble and gave him much-needed discipline. Unlike acting, this was language familiar to his family’s tongue: boxing. “I fully believed that was what I was going to do for a long time,” says Swindells. “Because coming from a working-class family, being an actor wasn’t really an acceptable thing for me to allow myself to believe I was going to do. And for them to believe that I was going to do.”

And this worked for Swindells until, well, it didn’t. He grafted, gave it everything, won bouts. “There’s a certain degree of control that you have, and my childhood was very much out of control.” At 17, he was injured and the pause caused him to ask: did he want to get punched in the head for the rest of his life? The answer was no. So, while the teenager worked out what he did want to do, he worked with his brothers to build fences.

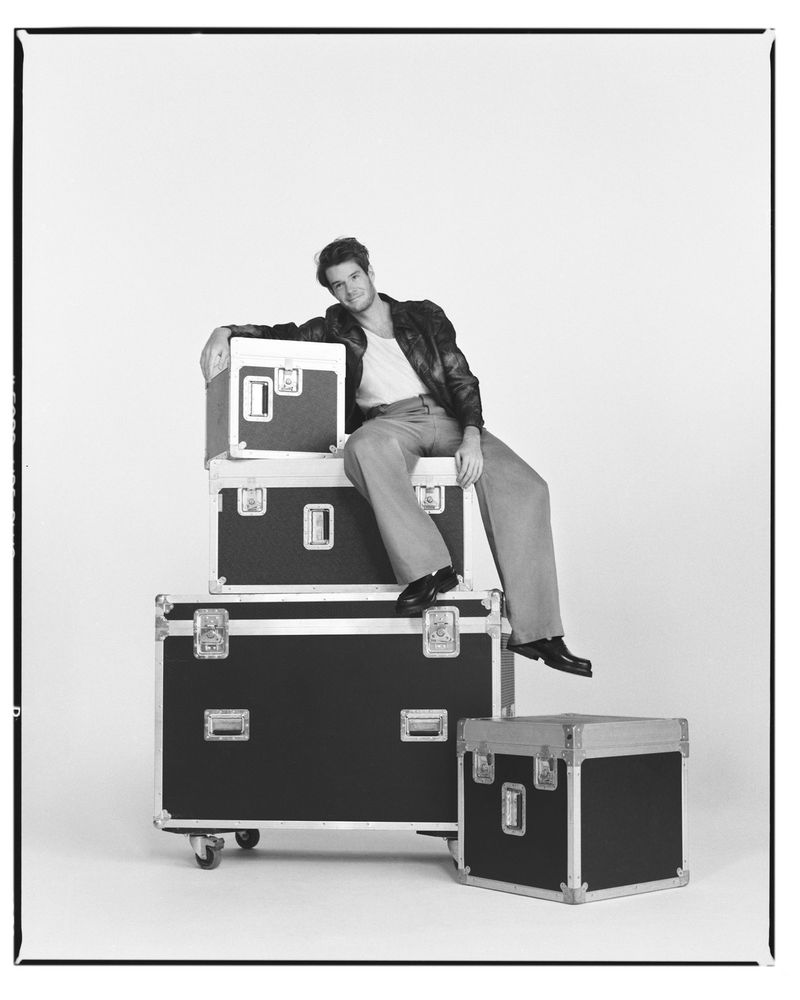

“I was just digging all day, digging into the ground, which was humbling.” Humbling it may have been, but Swindells knew that he needed to make it out. “There is no better way to motivate you than to do a job that you hate,” he says. “I was not built to be a fencer. I have skinny arms and small bones; I’m not the brutish Goliath that my brothers are when it comes to manual labour. I just spent the whole time in my imagination to get through it.”

When the lightbulb moment came – “Oh, I can get out of here by doing this” – it came from the very thing he’d dismissed as not for the likes of him: acting. He tested the water with friends by joking about auditioning. The audition was for acting classes, which then led to his first play, Mr Franz Kafka’s The Trial and community theatre (during which he slept on his brother’s sofa). And just like that, he’d found what he was meant to do for the rest of his life.

“With acting, people were telling me that there was something there quite early on, and that was a really important moment in my life.” And not only that, he had his family’s approval to boot. “They were incredibly supportive and much to my surprise were really wonderful.”

Swindells’ first-ever professional job was in Mr Gerard Butler’s 2018 blockbuster The Vanishing. “I’d done hundreds of auditions by that point,” says Swindells. “I probably was at my wits’ end with things and went into that audition a bit brazen because of that. And for whatever reason, that was something they liked.” It’s only now, three years on, that he fully appreciates what an insane opportunity it was “suddenly going from digging homes to abseiling down a cliff in a film while Gerald Butler holds the rope at the other end.”

But still lurking were unresolved issues from the actor’s childhood. Swindells was raised by his father, grandparents and other relatives after his mum died of cancer when he was just seven. In his second film VS., Swindells played an aggressive teenage boy who’d been raised without a mother. The parallels with his own life are clear, but were they difficult? “They were difficult,” Swindells carefully answers. “But it was the right time for me to look at those things and something I think was meant to be, to delve into that stuff. Whereas for most of my life I’ve been running on adrenaline and hadn’t really stopped to think about those things. It was definitely a bit of a traumatic experience going back to that place. But in hindsight it was something that really helped me.”

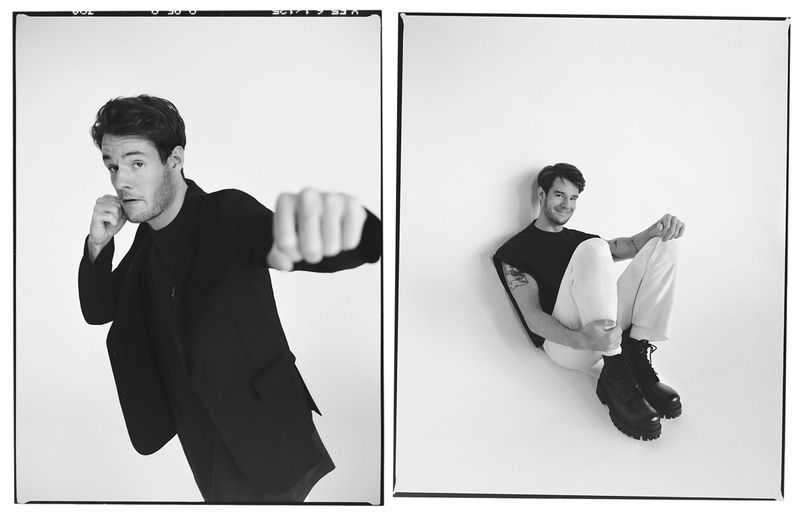

Since then, he truly hasn’t needed to look back again. He’s currently starring in the acclaimed BBC drama Vigil and has just finished a 10-week shoot in the Sahara desert for SAS: Rogue Heroes, an upcoming series from Peaky Blinders creator Mr Steven Knight, in which he plays a lieutenant and founding member of the SAS (“I was doing my best posh acting”).

It’s only been a handful of years, but a million miles from where he was: digging holes and quite literally fighting his way out, no parent with a fat wallet greasing his way. “I was always very lucky in other ways,” he says. “People always gave me a chance and let me into the room and heard me out. I would rather have that over being given 20 quid from my dad or whatever.”

What is this, I ask him as our time together dwindles: independence? Resilience? He takes a beat to think. “Yeah, it’s important for a young man who doesn’t have anything else, but there comes a time where you don’t need those things anymore. If you’re fortunate enough anyway, as I have been. All that stuff that you’ve put up to survive for so long, you don’t need. Because you don’t need to act out of fear anymore.”

His motivation may have receded into memory, but Connor Swindells doesn’t need it to be truly great. He may not be the rule: but he’s the exception.

Sex Education season three is available on Netflix from 17 September. Vigil airs on Sundays at 9.00pm on BBC One and on BBC iPlayer