THE JOURNAL

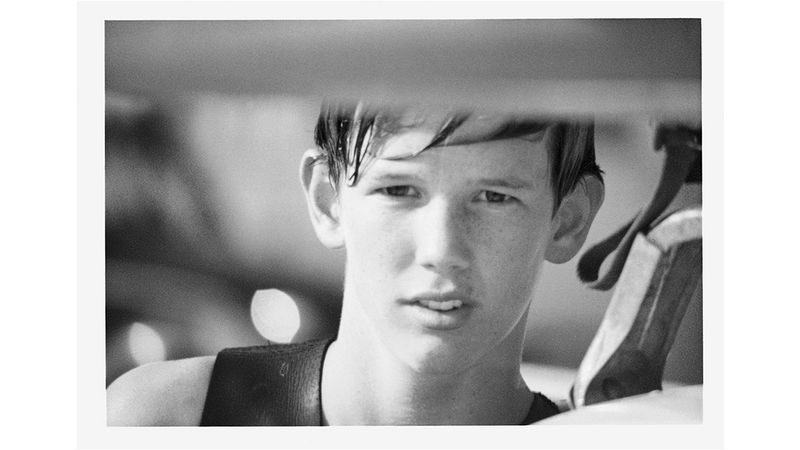

Mr William Finnegan, Grajagan, Java, 1979 © Mike Cordesius

Mr William Finnegan’s new memoir Barbarian Days is a rare thing – a work of literature about a life spent chasing waves.

Not long ago Mr William Finnegan found himself chatting with another surfer off the coast of Baja. Conversations in the line-up (the queue where surfers jockey for waves) are usually brief and technical. “This guy just started talking about Playing Doc’s Games. Telling me I should read it,” says Mr Finnegan, referring to a New Yorker article from 1992 about big wave surfers who congregated around San Francisco’s Ocean Beach. “I told the guy, ‘I wrote Playing Doc’s Games’, but he didn’t believe me.”

One can hardly blame the fellow, for the stereotypes of sun-addled surf bum and tweedy staff writer at The New Yorker are far apart. But it is the journey from the former to the latter that propels the narrative of Mr Finnegan’s new memoir, Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life. A political journalist by trade, the 62-year-old author is more likely to be found covering civil unrest in Africa or a Mexican drug cartel than he is contributing to surf ’zines. Nevertheless, it’s this unique ability to bring a journalist’s eye to surfing while remaining a devout practitioner that helps to explain why his new book has arrived to rave reviews and is an instant New York Times bestseller. Writing in The New York Times Magazine last month, critic Mr Jay Caspian Kang, called it “without a doubt, the finest surf book I’ve ever read”.

“There’s a world of difference between writing about surfing for surfers and for general interest readers,” says Mr Finnegan of the challenge he faced in writing Barbarian Days. “There’s a big hurdle if you’re trying to get non-surfers into the water and keep them oriented so they know what’s going on and give them some stake in the outcome of the scene.” He feels that too many writers fall back on easy outs such as creating false stakes, false drama.

The author as a young boy in Honolulu, 1967 William Finnegan

In order to get casual readers to understand surfing, he tucks a lot of the technical explanations into the opening chapter titled “Off Diamond Head”. There the reader meets Mr Finnegan as an eighth grader who has just been dropped into two new worlds. His father, an assistant director of television programmes, has relocated the family from California to the Kaimuki section of Honolulu. At Finnegan fils’ new junior high school, the haoles (as the natives called the white people) are a minority.

“My orientation programme at school included a series of fistfights,” he writes. The Pacific Ocean, beckoning at the end of his street, becomes his salvation. At his local spot, now known among locals as Cliffs, he “felt free to pursue my explorations of the margins. Nobody bothered me. Nobody vibed me. It was the opposite of school.”

Aside from explaining sets, barrels and other bits of surfer lingo, he is careful in this introductory section to make sure that the lay reader understands the amount of punishment, frustration and glimpses of nirvana that are part of a surfer’s education. Or as he writes in the book, “The whitewater tore the board from my hands, then thrashed me, holding me down for sustained, thorough beatings. I spent much of the afternoon swimming. Still, I stayed out till dusk. I even caught and made a few meaty waves. And I saw surfing that day – by [the legend] Leslie Wong, among others – that made my chest hurt. Long moments of grace that felt etched deep in my being: what I wanted, somehow, more than anything else. That night, while my family slept, I lay awake on the bamboo-framed couch, heart pounding with residual adrenaline, listening restlessly to the rain.”

Path to the water, Kulamanu house, 1966 William Finnegan

His internal soundtrack was not The Beach Boys (even though he has ridden every spot name-checked in “Surfin’ USA” with the exception of Australia’s Narrabeen and Waimea Bay); his was a different 1960s – one wherein he tries to ride maxed-out Honolua Bay in Maui while on LSD. The book unfolds in a series of 10 chapters tracing his evolution from what surfers call a “grommet” (or rookie) through his years as a “feral traveller”. In 1978, in his mid-twenties, he sets off with his friend and fellow aspiring writer Mr Bryan Di Salvatore on their own four-year endless summer going from atoll to atoll in the South Pacific in search of the perfect wave.

He becomes one of the very first people to surf what many now consider one of the finest waves in the world – Fiji’s Tavarua (a location he returns to in the book’s final chapter, although as the paying guest of a new luxury surf lodge). Along the way, the undertow of responsibility pulls him first to South Africa in the late 1970s where he teaches in a segregated school and decides he wants to be an author. “I had written several drafts of novels and even though I was a surf bum, I was constantly taking notes and filling up journals,” he says of his professional awakening. “Teaching in that high school in South Africa was a Damascene moment: I realised I really, really wanted to do political journalism.”

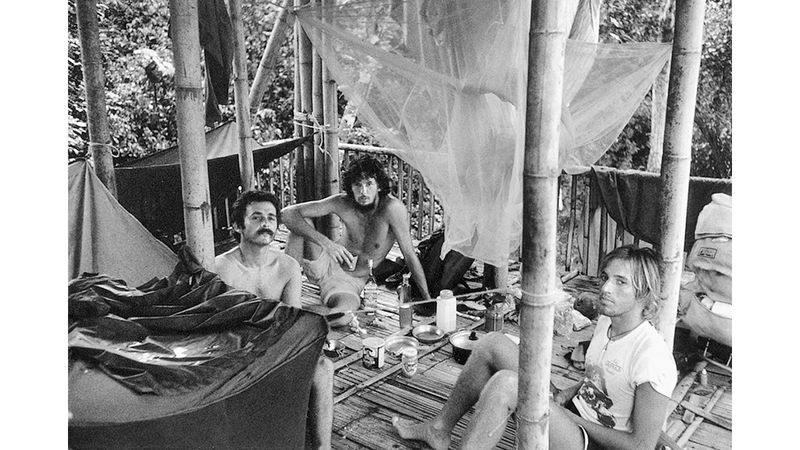

From left: Messrs Di Salvatore and Finnegan with unknown, Grajagan, Java, 1979 William Finnegan

After moving to San Francisco and writing freelance pieces for different magazines, he cracks The New Yorker. “I came at them from left field. I pitched a story over the transom, and the [editor-in-chief] Mr William Shawn was amazingly open to the idea of a story about a big wave surfer.” He spent seven years working on the article that became Playing Doc’s Games. In the interim he published three books – one about teaching in South Africa, a second about black journalists on a white newspaper in Johannesburg, and a third about Mozambique.

In hindsight the two main characters of that New Yorker article come to embody Mr Finnegan’s relationship with surfing: Doc is Dr Mark Renneker, a family-practice physician who kept a detailed record of every time he surfed; the other is Mr Bill Bergerson, a local carpenter whom everyone calls Peewee and is described by Mr Finnegan as one of the most natural surfers he’s ever seen. It is this tension between thinking about surfing and being in the moment that the book’s title alludes to. The phrase “barbarian days” comes from Mr Edward St Aubyn’s novel Mother’s Milk: “He had become so caught up in building sentences that he had almost forgotten the barbaric days when thinking was like a splash of colour landing on a page.”

Tavarua Island, Fiji, 1978 William Finnegan

Even as Mr Finnegan moves to Manhattan in the late 1980s and appears to be moving away from his barbarian ways into a more conventional lifestyle (a wife, a child, an apartment, a staff position at The New Yorker), he still feels the need to test his mettle in bigger and gnarlier conditions. Together with a new surfing buddy Mr Peter Spacek, he develops a fascination with a series of spots on the island of Madeira, off the coast of northwest Africa. This penultimate section includes some of the most harrowing surf scenes – all the more dramatic when one considers that there are people at home who are dependent upon him, and at 50 his body can’t spring off the canvas after an aquatic beat down as readily as it once did. In the patois of surfing, the author is now at an age when a long board beckons (it is easier to spring up on a long board).

“I haven’t gotten one yet. I was in Baja a few weeks ago and the waves were small so I rented one. It was really fun,” he says in a way that makes one wonder whether he is ready to accept his limitation or another trip to Fiji is just around the corner.

Buy a copy of Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life here