THE JOURNAL

In his upcoming book, Revolutionary Acts, Mr Jason Okundaye writes, intimately, sensitively and searingly, the accounts of seven elders who shaped Black gay Britain. It’s both a riveting read and a vital exercise, transforming oral lore into written text while also carving out their place in LGBTQ+ history. But, perhaps most importantly, Revolutionary Acts poses the question: how many more forgotten Black histories are yet to be uncovered? What about undocumented accounts now lost, most likely for ever? This is why UK Black History Month continues to be so vital, an opportunity to both highlight and redress that erasure, in the hope that one day the very need for a Black History Month is obsolete.

Recovering and preserving the past is crucial, but history is ever-evolving, always hurtling towards the present. Who is narrating our stories and creating fully fleshed-out portraits of what it means to be Black and British in 2023 – not just for now but for posterity? To answer the question, MR PORTER sought out the authors, poets and screenwriters who are creating a new canon of work that showcases Black Britishness in all in its multitudes: the beautiful, the raw, the painful, the mundane. Here, five bright young storytellers discuss inspirations, identity, self-expression and style.

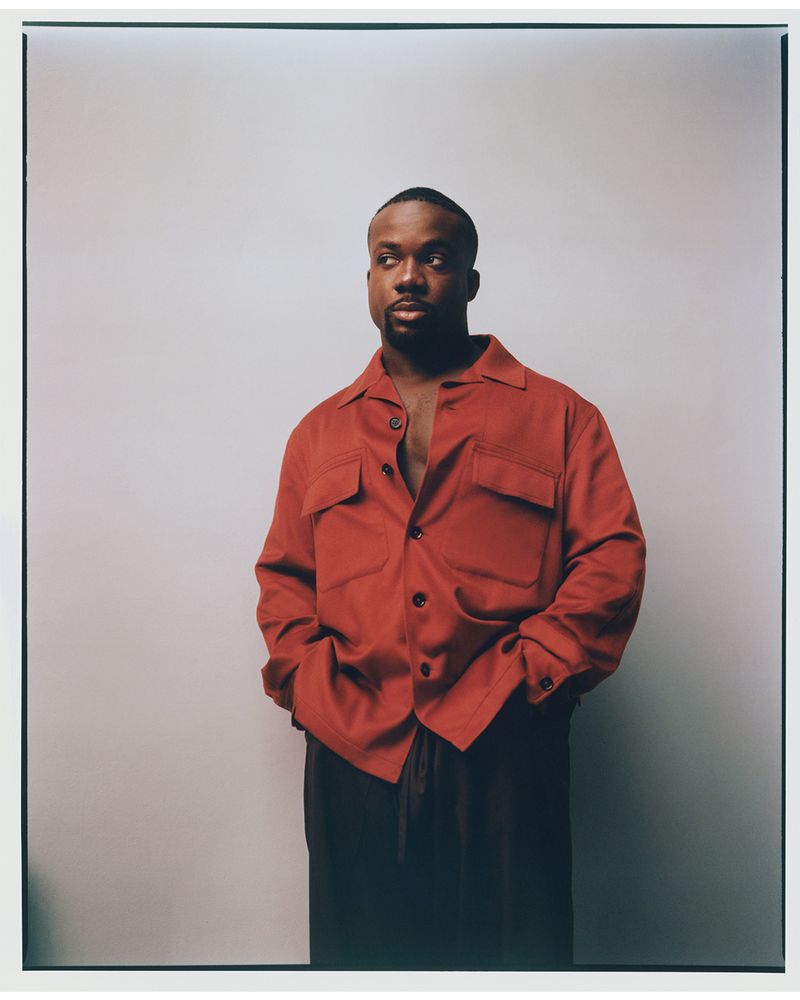

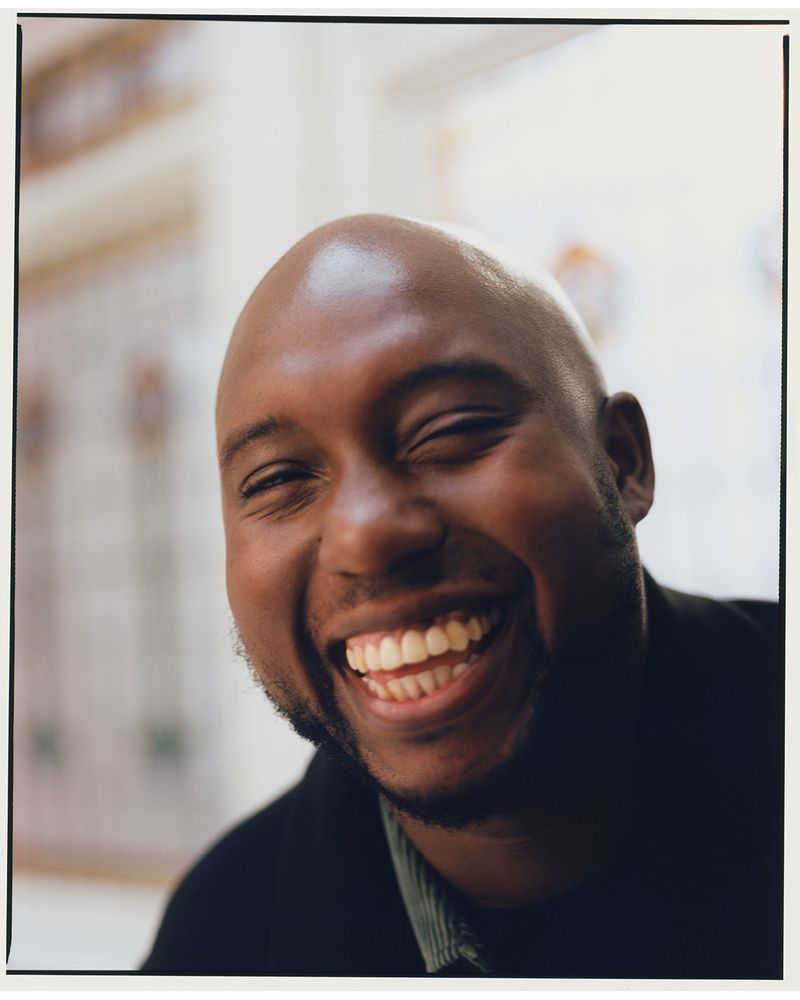

01.

Mr Jason Okundaye

Mr Jason Okundaye is a journalist who writes about culture and politics for publications including The Guardian, Evening Standard and the London Review Of Books, and has profiled everyone from Sir Steve McQueen to Pusha T. Next year sees the release of his first book, Revolutionary Acts, which narrates the history of Black gay Britain through the stories of seven men in his native south London.

How did Revolutionary Acts come about?

Since university, I had this idea that I’d been mulling over about looking at some of the histories of Black gay men in Britain. It stemmed from my final-year dissertation, when I could barely find anything out there. I knew that it existed, and I had some evidence that it did, but I would’ve needed to do something more substantial to recover some of this information. I kind of parked the idea in the back of my mind as something that I’d like to return to at some point, which ended up being sooner than I thought.

With so little publicly available, how exactly did you gather research for the book?

I found [activist] Marc Thompson first and had a long conversation with him, where I learnt the names of various people who might be worth talking to. It was a very organic process, and I wasn’t sure what the final cast was going to end up looking like when I started. I also visited the London Metropolitan Archives, which has a Black LGBTQ+ archive, and went to the British Library to get copies of The Voice newspaper, which had documented some of the events the men were talking about. But the rest of it was pretty much entirely oral history and discovering things that they had in their possession, such as old newspaper clippings, videotapes and flyers.

What do you hope the legacy of your book will be?

I’ve written it in such a way that I’m hoping that it doesn’t date. But mostly, I hope that the men who are featured in the book feel like it does them some justice, and that it pioneers an approach to how we look at the history of this country and the kind of people who we turn to for those accounts.

Are there any writers past or present who you turn to for inspiration?

Aniefiok Ekpoudom, who has a book coming out called Where We Come From, is a brilliant writer. It’s incredible to have someone who’s a peer in this industry who’s writing at that level and with such incredible detail when chronicling Black Britain. The writing and thinking of Stuart Hall has always been an inspiration to me, historically, and I really like the work of Samuel Selvon, the author of The Lonely Londoners.

There’s a long legacy of writers with incredible sartorial style. Do you have any particular favourites?

James Baldwin, of course. He’s the number one for fashion. And Sean Hewitt, who’s a contemporary poet and author. Whenever he’s going to pick up a prize or promote a new book, he always dresses incredibly snappily. He’s someone I’m taking notes from to make sure my look for the book launch is on point.

02.

Mr Otamere Guobadia

Since founding the queer magazine No HeterOx while studying law at University College, Oxford, Mr Otamere Guobadia has written about identity, style, pop culture and sexuality for an array of publications. Next year, he releases his debut poetry collection, Unutterable Visions, Perishable Breath, which probes agency, queerness, desire and beauty.

How did you get into poetry?

I’ve always written poetry, but university was a time when I finally gave myself the licence to do it. I think people are so embarrassed of poetry because, of all the written forms, it sometimes feels the most revealing. I feel like at some point, something shifted in those years, and in the years that followed, and I just felt like what I had to write in verse mattered.

What does the notion of queer writing mean to you?

When I’m thinking about queerness, I’m thinking about political identity, but also I’m interested in queering the forms themselves. I think most people’s minds are quite a queer thing with no straight lines, and so much of writing is attempting to reconcile the madness of a mind into digestible forms. Part of the appeal of writing Unutterable Visions, Perishable Breath to me was to fight against this notion of a coherent, curated body and play with that tension.

There seems to be a real synergy between the way you dress and the way you express yourself in your writing. What does personal style mean to you?

Clothes have a magnifying effect on me. They’re able to amplify my mood, amplify my confidence. It’s a mode of expression that I truly delight in. I also think that clothes and adornment are important parts of becoming. People talk about stripping away to find your true self, but I think adornment and artifice are some of the most important parts of discovering who you are.

What sort of clothes are you finding yourself drawn to?

I think my style has extremities and poles. I’m really in my suit-and-tie era at the moment. I love a shoulder pad, I love a cinched waist, I love a waistcoat. I love polish more than anything, but I also love to subvert expectations of polish. I enjoy playing the dandy – or rather, the dandy’s preoccupation with dress and willingness to lean into fashion statements that might be seen as silly by serious society is perhaps where I identify most.

Whose writing is exciting you right now?

I think Emma Dabiri is one of our greatest working intellectuals right now. She writes so stimulatingly about beauty, and just the conversations that I’ve had with her really excite me. She’s also as intelligent as she is glamorous, and I think that’s a beautiful combination.

03.

Mr Iggy London

Mr Iggy London is a writer, poet and filmmaker from Newham in east London. This year, he released the short film, Area Boy, a poignant coming-of-age tale, which premiered at the Venice Biennale. He’s also the editor of Mandem, a recently published anthology of writings on Black British masculinity that touches on class, mental health and more.

How did you first get into writing?

I grew up watching Def Jam Poetry and seeing the likes of Erykah Badu and Common talk about real-life issues. For me, poetry became a device to break down some of the more difficult topics and make sense of things I didn’t really understand. At university, I got into spoken word and started to perform at poetry nights. That’s really what inspired me to write reflections of what I saw in society and eventually developed into making narrative work.

Why did you feel the need to create Mandem?

I was having a conversation with a friend and thinking about what it would look like to have a blueprint for Black manhood. I wanted to make it easier for people to understand themselves by holding a mirror to society. Also, there was this stereotypical image of who “mandem” were and I wanted to debunk that. I thought about getting a bunch of poets, writers and creatives to basically write stories that were quite personal, but had masculinity as the thread. And I think it came about from trying to build something that the next generation could actually learn from, without feeling that they had to start up all over again.

Were there any other writers you looked to when you were putting together Mandem?

bell hooks is a huge inspiration, not just in my writing, but how I go about my work in general. For me, she’s one of the major voices on Black masculinity – I had read the likes of James Baldwin and Frantz Fanon, but with her work, I felt like I could really connect with the language and the representation of Black men in America, what they were going through. I think she was really able to break it down in a way which for me made sense.

In Mandem, you write about being teased for how you dressed as a teenager. How did you find the confidence to go against the grain and reject those constraints of masculinity growing up?

Growing up and being quite shy when I was young taught me a lot about observing people. I think I’ve used that to understand myself and what I’m about. And it was always funny to me how the tropes of Black masculinity never made sense – how skinny jeans were considered effeminate, but bejewelled jeans weren’t. It just goes to show that these roles that we put ourselves in are made up and sometimes we’re insecure about going against the status quo and project our own insecurities onto other people. I think, for me, it was always cool to be different and I never really wanted to conform.

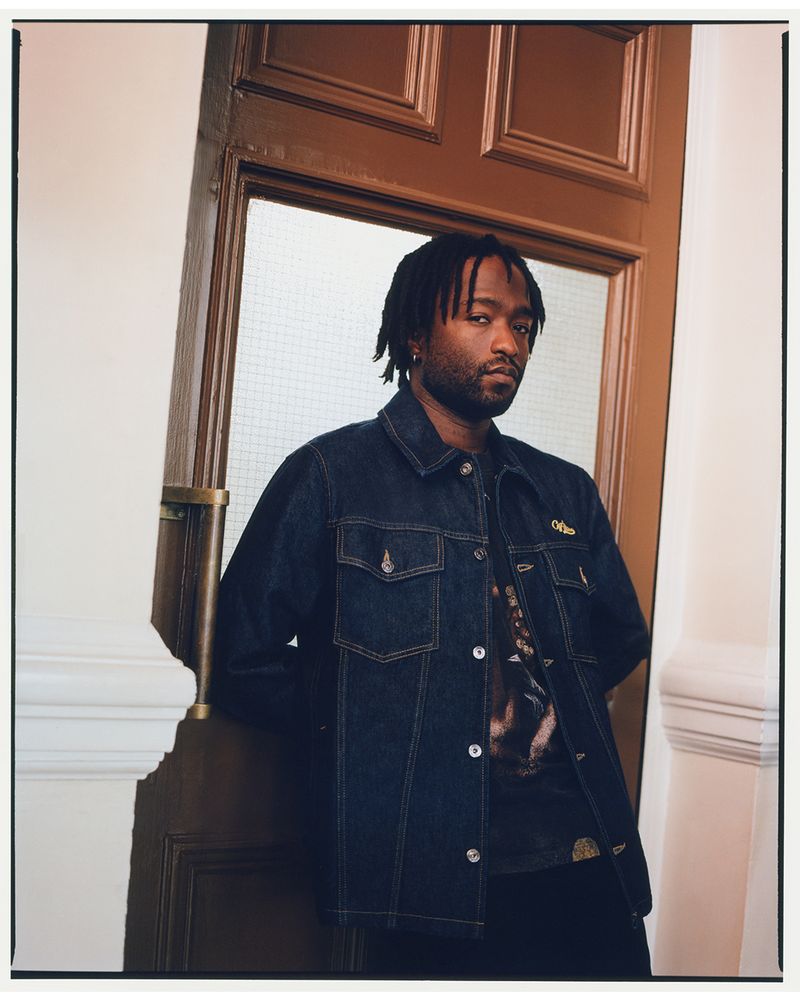

04.

Mr Adjani Salmon

Mr Adjani Salmon’s hit comedy series Dreaming Whilst Black, created with A24 and BBC, has brought the Jamaican-born auteur firmly into the spotlight and established him as an exciting new voice in screenwriting. The semi-autobiographical show, which follows aspiring filmmaker Kwabena as he tries to make his way in the industry, started life as a web series and earned Salmon the 2022 TV Bafta for emerging talent in fiction.

How did you decide that comedy was the genre for you?

I see myself as a storyteller, first and foremost. The first question for me is: what do I want to say? Then it’s: who do I want to say it to? And finally: well, what’s the best way to tell this person this information? With Dreaming Whilst Black, I wanted to get back into making web series and I knew that comedy is what does well on YouTube. And at the time, there was all the frustration of being in the industry and not being able to get a break. I thought, “If I’m making it for our community, how do I want that to look?” Humour just felt the best vehicle to have a lot of the discussions that we have in the show.

You’ve said that you wrote dozens of drafts for Dreaming Whilst Black. Why so many – and how did you know when it was ready?

We did about 45 drafts for the pilot alone. We were literally burning through scripts. But the fundamental rule of filmmaking is that the first draft of everything is shit. You have to constantly interrogate the story, the intentions, the characters, the lines. It’s really a process of building it up, pulling it entirely apart and putting it back together.

How exactly do you go from an initial idea to a final screenplay?

I feel like I come to filmmaking from a different lens because of my background in architecture. The question for me is: how do we design this story? When you’re creating a building, you have to think of the potential inhabitants – how you want them to experience and interact with this space. For me, it’s the same thing with storytelling. I do multiple drafts of outlining before I even get to the screenplay.

Both you and Kwabena in the series have these incredible locs. How did that become your style signature?

I actually grew my hair when I moved to England. I guess I thought no one’s here to police me, so I’m going to just grow it and see what happens. I was just doing it as a style, but the more my hair grew and the more pushback I got from it, the more I felt like it was a statement – like, I’m not going to allow you to tell me that my hair in its more organic state does not look good. Originally, I just wanted locs because I thought they were cool, but now it’s almost a symbol of my being unapologetic.

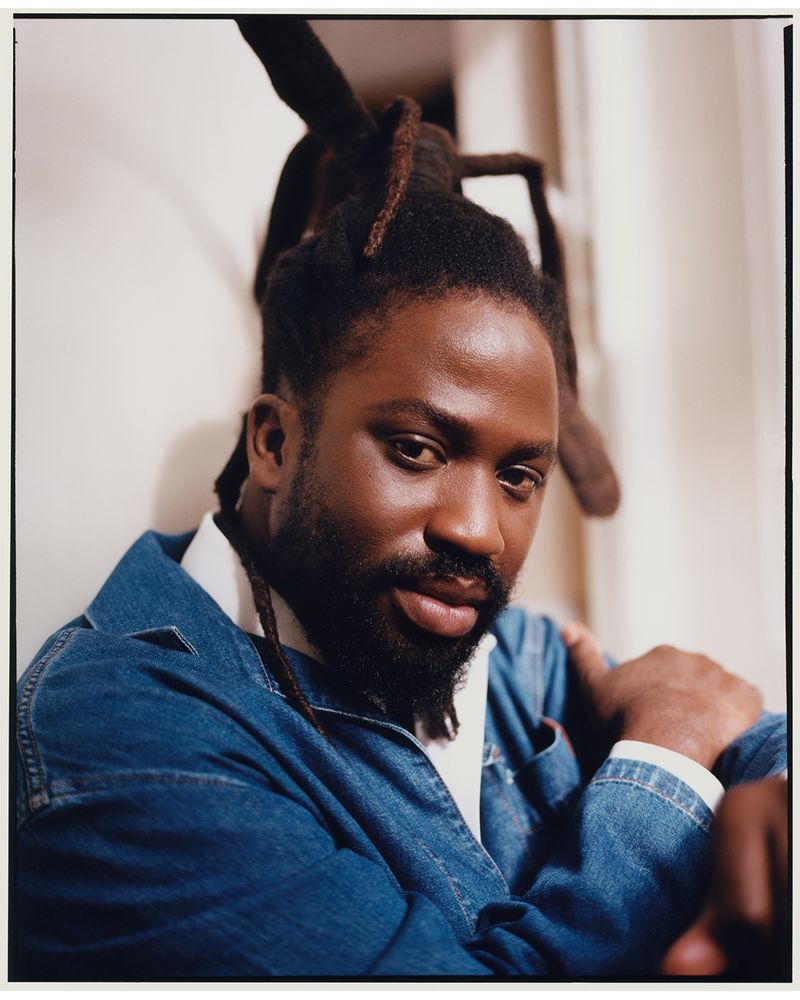

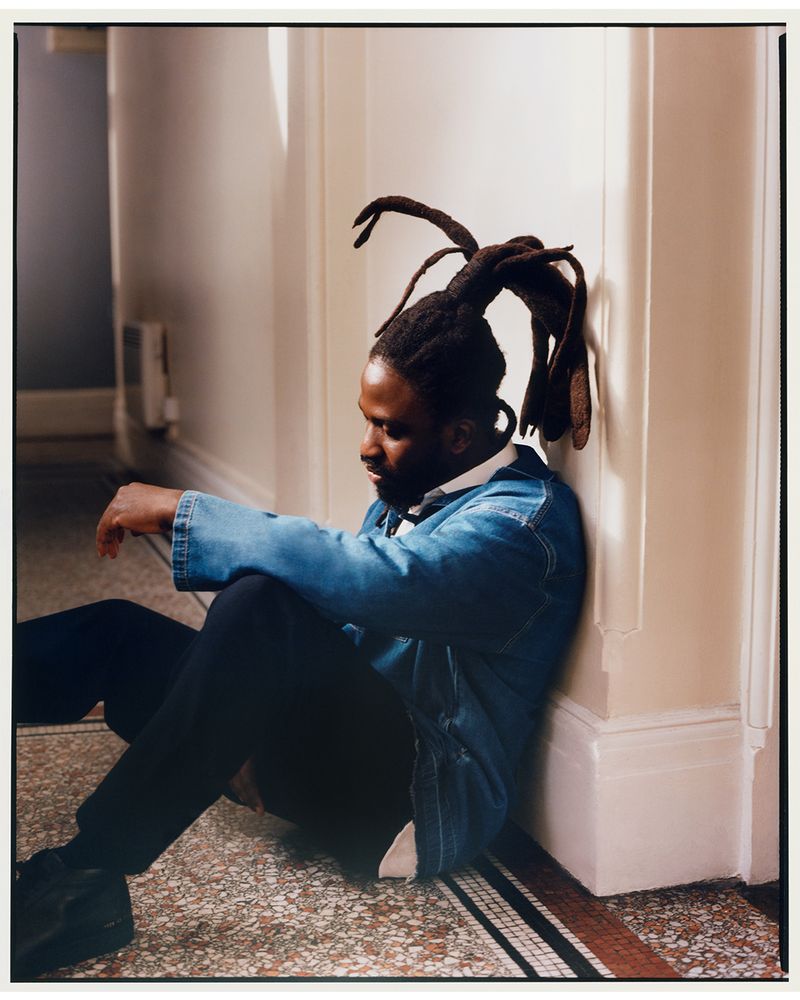

05.

Mr Caleb Azumah Nelson

In 2021, writer and photographer Mr Caleb Azumah Nelson published his debut novel, Open Water, a tender tale of young Black love, to critical acclaim, winning the Costa Book Award for First Novel. This year, he followed up with Small Worlds, an exploration of a father-and-son relationship set between London and Ghana, which he’s currently adapting for the screen.

Were there any books you’d say shaped you growing up and made you want to be a writer?

Reading Mallory Blackman’s Noughts And Crosses at eight or nine left a big mark on me. She was a local author as well, and that was maybe one of the first instances where I realised it was possible to tell stories for a living. I think when I first read Zadie Smith, too, that was a big shift for me and my writing practice. I’d been reading Baldwin and Toni Morrison, who are still big influences, but I think there was a real difference in being able to read someone who was directly reflecting my experiences coming from London. I could really recognise the story and these characters.

Where do you begin when writing a novel?

I feel like characters appear to me first, and then I try to allow space for them to really grow. And because so much of my work centres Black characters, it’s about trying to find a way of making them feel as honest as possible and affording them a sense of complexity. I’m not much of a planner – most of the time it’s just a blank page and some vibes. Oftentimes, I know what the emotion is that I’m trying to express; it’s just in the moment I’m trying to figure out what the container is.

Who are your wider artistic inspirations outside of literature?

The British-Ghanaian painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye is a big influence of mine – just the way she builds worlds and how her work centres these fictional Black characters who’ve emerged from her interiority. Her backgrounds are also as textured as the subject of the painting, and that’s something I’ve always thought about – how I can form the world around the characters and find of way of it feeling as real as possible to the reader.

Is there any advice that has stuck with you and that you pass on to aspiring writers?

The first time I met my agent, she said writing a novel was like fictionalising memory, and I’ve always been really intrigued by that. It’s not necessarily about writing something autobiographical, but rather the ways in which you might tap into your own memories or a collective memory to express a feeling or a notion. I also think so much of writing in whatever medium is about faith and about instinct. You’re coming to the page and putting words to things that don’t have them. For me, it’s about making space to trust myself in the process.